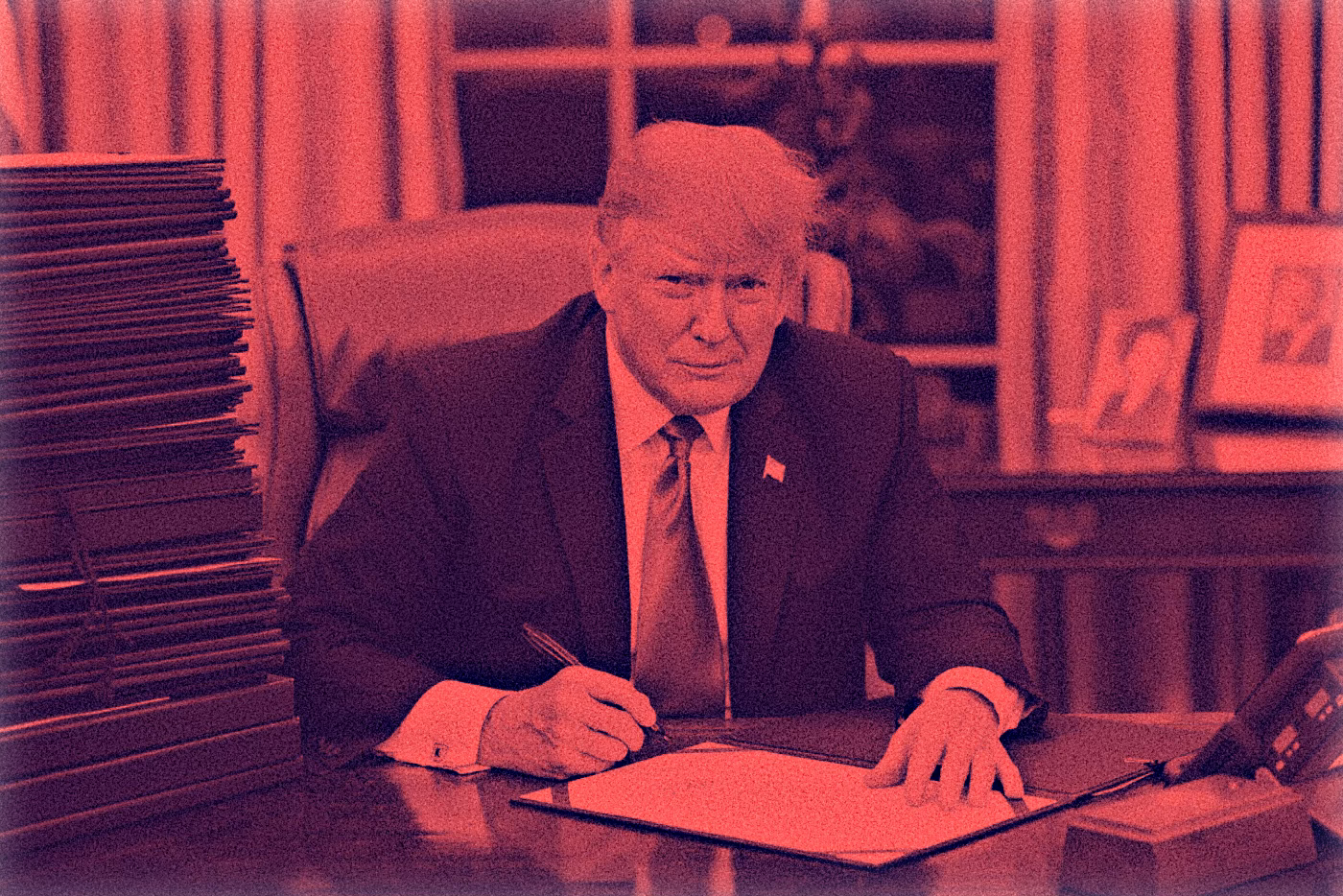

Trump’s Pardons Cover Every Conceivable Form of Corruption

He is doling them to crooks, cronies, campaign contributors, violent insurrectionists, child sex offenders, convicted drug dealers, and others

Since January, Donald Trump has been conducting a large-scale experiment to probe all the ways presidential pardon power can be abused. He has granted pardons to his own co-conspirators in crime and insurrection. He has given pardons as rewards for campaign contributions or for business deals that benefit his family. He has given away pardons sometimes just because he feels the rich and famous should have a “get out of jail free” card. And he has abused the pardon power to manipulate foreign elections and prop up right-wing authoritarians.

It is possible there are more ways to abuse the pardon power than Trump has found so far, but we would be hard pressed to think what they would be.

To be sure, previous presidents from both parties have issued sketchy pardons. Bill Clinton gave controversial pardons for Puerto Rican terrorists, supposedly to help Hillary Clinton’s Senate run in New York, and for Marc Rich, a wealthy campaign donor. But as usual, Trump is not content merely to match previous bad precedents.

He has abused the pardon power not just by granting pardons that are clearly and flagrantly corrupt in their motives, but also by pushing the constitutional limits of the pardon power itself.

Pardoning His Co-Conspirators

The pardon power granted in the U.S. Constitution is very broad, but it is not unlimited.

Article II gives the president “power to grant reprieves and pardons for offences against the United States, except in cases of impeachment.” This grant contains a few explicit limits: The president cannot overturn the impeachment of an official by Congress, and he can only pardon people for federal crimes, not state crimes. There is a good argument that there are other implicit limits on the pardon power as part of the constitutional order—things a pardon cannot do without undermining the rest of the Constitution. The pardon is intended as an instrument of clemency in special cases—not as an all-purpose escape hatch from the law. This has been contradicted by the Supreme Court’s notorious decision granting the president near total immunity, which implies he cannot be prosecuted for abuses of power like selling pardons. But the Court’s refusal to recognize this principle does not make the principle go away.

In the debates among the drafters of the Constitution, George Mason warned that an overly broad pardon power “may sometimes be exercised to screen from punishment those whom [the president] had secretly instigated to commit the crime and thereby prevent the discovery of his own guilt.” Mason’s warning was not heeded, and this is precisely how Trump has used the power. One of his first acts on returning to office was to issue pardons to hundreds of rioters from the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, including those who had viciously assaulted police officers. The aim of the riot was to physically threaten members of Congress in order to prevent the certification of Trump’s election defeat and keep him in office in defiance of the will of the voters. This was a crime Trump not-so-secretly instigated through months of false claims alleging the election was rigged, turned into a call to action in a speech earlier that day urging his followers to “fight” to “stop the steal.” Once he was back in office, he gained the power to screen from punishment the people who carried out those orders.

It should be no surprise that some of these rioters, having been pardoned for one act of political violence, keep on plotting new acts of political violence. In February, Proud Boys leader Enrique Tarrio was arrested at the Capitol (again) for assaulting a protester. In July, Edward Kelley, who was “the fourth person to unlawfully enter the Capitol building at the forefront of the mob” and attack an officer, was convicted for a new plot to assassinate “36 individual federal, state, and local law enforcement personnel” whom he blamed for his arrest on the Capitol riot charges. Christopher Moynihan was arrested in October for planning to assassinate House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries.

Some have committed unrelated crimes but in a way that is clearly emboldened by their pardons. Andrew Paul Johnson was charged in November for molesting an 11-year-old boy—and tried to silence his victim by offering to share an anticipated multi-million-dollar compensation for his Jan. 6 arrest, a payout championed by Trump.

Trump’s Justice Department has also taken a broad view of these pardons, arguing that they don’t just cover actions taken on Jan. 6 but also any unrelated crimes uncovered during investigations into the rioters. In one case, Trump issued a second pardon to make it clear that one of his rioters would also be let off the hook for an unrelated weapons charge. In a novel case, one rioter was even allowed to claim the prison time served for his Jan. 6 conviction as credit against a new charge for soliciting sex with a 15-year-old.

The Pardoned Class

Not content with pardoning the actual rioters, Trump also pardoned his accomplices in another aspect of his 2020 election fraud scheme: submitting fake slates to the Electoral College in place of the ones actually chosen by voters. These pardons are intended as a green light for future attempts to overturn elections through fraud and violence.

Since the Constitution gives states primary control over elections, most of Trump’s co-conspirators in the fake elector scheme have been charged under state laws, and a presidential pardon is not supposed to apply to them. Yet Trump’s allies are insisting that his pardons should invalidate the state-level cases. Even if they’re not used to quash charges at the state level, these pardons “could have the effect of barring a future administration from bringing federal charges against these individuals,” as Kim Wehle pointed out in The UnPopulist.

Yet these pardons imply an even greater distortion of the pardon power, because they are not tied to specific acts or charges. They are blanket pardons for a whole range of unknown acts by unnamed people. The text of the pardon provides immunity to “all United States citizens for conduct relating to the advice, creation, organization, execution, submission, support, voting, activities, participation in, or advocacy for or of any slate or proposed slate of presidential electors, whether or not recognized by any state or state official, in connection with the 2020 Presidential Election.” Taken literally, this also applies to ordinary vote fraud cases that were not connected to Trump’s scheme.

There is a common-sense argument that valid presidential pardons must be specific, that they cover only the explicitly listed crimes of specifically named people, and not every crime anyone may have committed during a certain period of time.

The kind of blanket immunity Trump has been providing, both to the rioters and to the fake elector fraudsters, opens up a novel abuse of the pardon power. It effectively creates a special class of people, the pardoned class. As the president’s staunchest and most fanatical supporters, they are essentially above the law.

The ‘Get Out of Jail Free’ Card

This is reinforced by a series of “MAGA pardons” for Trump’s political allies, from a corrupt sheriff convicted in a “cash for badges” scheme, to disgraced former Congressman George Santos, who may have diverted election funds to support his lavish lifestyle but “was 100% for Trump,” to the healthcare fraud conviction of the husband of Republican Congresswoman Diana Harshbarger, a Trump ally.

But in many cases, it’s all about the money. Trump pardoned an executive convicted of tax fraud after the executive’s mother gave $1 million at a Trump fundraiser. The judge who sentenced him said: “there is not a ‘get out of jail free’ card for the rich.” Under Trump, there is.

Trump is also very interested in pardoning people who have made him richer. In October, he pardoned cryptocurrency fraudster Changpeng Zhao after Zhao’s company, Binance, made a deal to boost World Liberty Financial, the Trump family crypto venture.

Essentially, pardons are now for sale, and not just by Trump but also by the circle around him. When asked about Zhao’s pardon, he professed not to know who he is, saying only, “A lot of people say that he wasn’t guilty of anything.” This is a common response when Trump is asked about pardons: that he is only doing what he was told by others. So who was doing the telling, and what incentives did they have?

Consider the case of Joseph Schwartz, convicted of pocketing millions of dollars of his workers’ employment taxes in order to prop up his failing business. He just received a pardon from Trump—after paying $960,000 to Jack Burkman and Jacob Wohl, a pair of bottom-feeding conservative provocateurs who have themselves been convicted of fraud in voter suppression schemes. This means that they are very well connected in Trump-world. They “contacted Congress, the White House, and the Justice Department on Schwartz’s behalf,” they got the right people telling Trump that their client had been treated unfairly, and they got him sprung from jail. It turns out it only costs a million dollars to get the right people talking to Trump on your behalf.

Sometimes, Trump volunteers all on his own to rescue fellow celebrities. He gave a pardon to Rod Blagojevich, the corrupt former governor of Illinois who had also been a contestant on Trump’s show, The Celebrity Apprentice. He also pardoned reality TV stars Julie and Todd Chrisley, whose lavish televised lifestyle turned out to be built on fraud and tax evasion. Trump seems to regard it as one of the privileges of wealth and fame that if you rise to a certain level, you deserve legal impunity—especially if you support him.

That’s another part of the quid pro quo: not just money, but public support and praise. Pardons can be sold for flattery, too.

It is important to grasp the sheer pace of these pardons—more than 1,500 so far this year. The average president issues no more than a few hundred pardons, even in two terms. Trump’s pardons are not special clemency granted in unusual cases. They are a general amnesty for white-collar crime.

A Strongman Pardons a Strongman

Trump is handing pardons to political allies, not just at home, but globally. You might not think U.S. pardons could be a tool for propping up strongmen abroad, but there is at least one case in which such a strongman was convicted in American courts—and Trump just freed him.

Even as he uses drug smuggling as an excuse to blow up random fishermen in the Caribbean, Trump just pardoned former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, who was extradited to the U.S. and convicted for running a giant cocaine smuggling ring out of his presidential office. Why Hernández? Partly because he backed Trump’s anti-immigration efforts when he was in office, but also because Trump wanted to boost Hernandez’s successor from his right-wing political party in this week’s Honduran elections. On social media, Trump paired his announcement of the pardon with a call to vote for Hernandez’s successor.

This is a corrupt pardon used as a tool for promoting right-wing authoritarian politics abroad. Given Trump’s own predilections, it also suggests that he wants to establish that someone who holds high political office can be held immune from all prosecution afterward.

These abuses of the pardon power are offering us a perverse kind of service, in a way. By pushing every constitutional provision to its limits and beyond, Trump has thoroughly explored and exposed the hidden weakness of our constitutional system. In these cases, he has been proving George Mason right, and then some. The presidential pardon power is too broad and unrestricted. It puts too much power in one man’s hands, with too few constraints.

There are various proposals to curb the president’s abuse of this power, some starting with what Congress could do right now, and others that would require amending the Constitution. Mason’s original idea was to require Senate approval for pardons in the same way as for Cabinet appointments and treaties. Or perhaps a reformed pardon power should be given, not to one person, but to a special tribunal with members appointed by the president and both houses of Congress.

We can debate what form pardon reform should take, and which are politically possible. But after the sheer scale and brazenness of Trump’s abuse, we cannot debate the urgent need for it.

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

Sorry for being european, but how exactly is it possible that a convicted felon, insurrectionist, twice-impeached, blatantly corrupt and unlawful person is eligible for any office? I know America is extreme in every respect, but this just seems silly. Like Flying Circus North-Minehead by-election kind of silly.

Who could think or belive like 20 years ago that one day the USA is going to have a president who wants to govern as a dictator?