The Colorado Governor Should Reject Trump’s Demand to Pardon a Convicted Election Saboteur

Jared Polis will jeopardize our democracy by freeing Tina Peters

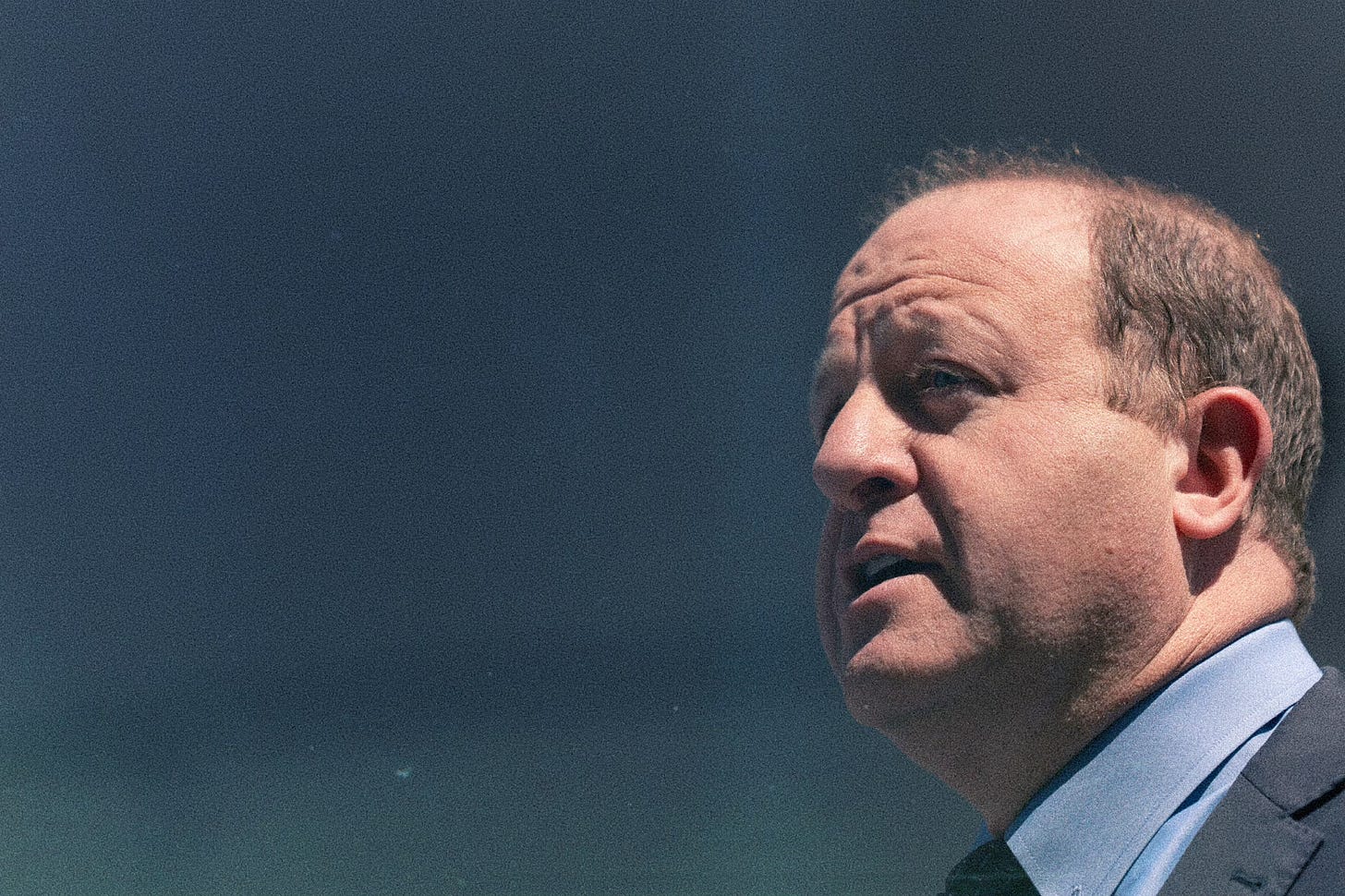

There are few principles more essential to a liberal democracy than the idea that the law applies equally to everyone, and that abuses of public power—especially ones aimed at sabotaging democratic processes—carry real consequences. That principle is now under pressure, as Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, a Democrat, has said he is considering commuting the sentence of former Mesa County clerk and recorder Tina Peters.

Peters is currently serving a nine-year sentence for her actions in compromising the integrity of her county’s voting machines, illegally giving access to unqualified conspiracy theorists attempting to prove spurious claims about the 2020 presidential election. Peters peddled those same false claims herself, corruptly tried to cover up what she had done, and, most directly, required Mesa County to spend significant sums of money to replace the machines she rendered unusable.

Compassionate release based on age or infirmity can be a humane, sensible, and even necessary feature of the criminal justice system. Peters is 70 years old and has been in prison for just over a year. As it stands, she will become eligible for parole in Dec. 2028, when she will be 73. In many cases, that fact alone would warrant a careful, good-faith reassessment of whether continued incarceration meaningfully serves public safety, deterrence, or rehabilitation.

But mercy is not dispensed in a vacuum. Clemency is not an abstract exercise in benevolence; it is a judgment call that must weigh compassion against accountability, and individual circumstances against societal consequences. In Peters’ case, those countervailing considerations weigh decisively against cutting short her well-earned sentence.

An Attack on Elections Is Not a Victimless Crime

Peters’ crimes were deliberate acts carried out by an election official who understood exactly what she was doing and why it was illegal. She showed plain consciousness of guilt, including by deliberately disabling security cameras to cover up the crime. Using her position of public trust, Peters facilitated unauthorized access to secure voting systems and enabled the copying and dissemination of sensitive election software and data. And she did so in service of a conspiracy theory intended to subvert electoral democracy itself.

That context matters. Elections are not just another administrative function of government. They are the mechanism by which legitimacy itself is conferred, and they are how we keep the peace in a society where our disagreements are resolved under the rule of law. When an elections official sabotages that mechanism from the inside, it strikes at the very premise of a democracy that political disputes are resolved through ballots—not force, fraud, or coercion.

This is often discussed in abstract terms, but in Mesa County the damage was painfully concrete. Because Peters compromised the integrity of the county’s voting equipment, those machines could no longer be trusted for future elections. They had to be replaced entirely, at significant cost to local taxpayers. That expense was not hypothetical, symbolic, or ideological. It was a real financial burden, and a significant imposition on the county’s finite resources.

That replacement cost also underscores an important point: election interference is not a victimless crime even when no votes are ultimately faked or miscounted. The integrity of an election system depends on public confidence in its security. Once that confidence is shattered, the system itself must be rebuilt. Peters didn’t just endanger democracy in theory; she forced her county to pay to restore the minimum conditions for trustworthy elections.

Any assessment of clemency that downplays this harm misunderstands the nature of the offense. Crimes against democracy are not lesser crimes because their effects are diffuse. They are more serious precisely because they are an attack on society as a whole.

No Remorse, No Reckoning

The case for a lighter sentence is most compelling when it is paired with genuine contrition and rehabilitation, and our criminal justice system rightly takes this into account. Mercy makes moral sense when the person receiving it has demonstrated some recognition of wrongdoing, some acceptance of responsibility, or at least some understanding of the harm they caused. Tina Peters has done none of this.

To the contrary, she remains flagrantly unrepentant. “I’m not a criminal and I don’t deserve to go into a prison,” she insisted at her sentencing. She continues to cast herself as a political prisoner and folk hero, rather than as a public official who violated the law and abused her office. She has never meaningfully acknowledged that her actions put election workers at risk, undermined trust in democratic institutions, or cost her county significant sums of public money. Instead, she has doubled down on the same election denialism that motivated her crimes in the first place. That has included, in recent court arguments, insisting her conviction should be overturned because she was acting according to federal law when deliberately lying to state officials, a ludicrous claim.

As Judge Matthew Barrett explained at Peters’ sentencing, showing contrition and rehabilitation is properly a long-established factor in determining how long a convicted defendant’s incarceration should last. Put simply, Peters talked herself into a longer sentence because she conceded no wrongdoing, cast herself as a victim, and plainly intended, as she still does today, to encourage others to commit similar offenses in service of anti-democratic lies. “I’m convinced you’d do it all over again if you could,” Barrett concluded, calling Peters “as defiant as any defendant this court has ever seen.”

That matters because clemency is not merely about reducing suffering; it is also about signaling values. Granting a commutation to someone who persists in denying reality and rejecting accountability sends a message—not just to the individual, but to the public—that defiance can be rewarded. It is deeply corrosive to the rule of law, and contrary to the legitimate purposes of the clemency power.

It also creates an obvious equity problem. Peters is far from the only person in their 70s currently incarcerated in Colorado state prisons. Many elderly prisoners are serving time for crimes far less corrosive to the constitutional order than election sabotage. To single her out for special treatment would invite a troubling inference: that notoriety, political usefulness, or media attention count more than neutral principles of justice.

If releasing elderly prisoners early is to be a general policy, it should be applied through clear standards that do not hinge on partisan mobilization or presidential pressure. Otherwise, pardons and commutations become indistinguishable from corrupt favoritism.

A Dangerous Attack on State Sovereignty

The most alarming dimension of this debate is not about Peters herself, but about the political forces seeking to intervene on her behalf. The only reason we are even having this discussion is because Donald Trump has been demanding Peters be released. He has explicitly threatened the state of Colorado to undo a legitimate state conviction and sentencing. That context cannot be ignored, because yielding to it would carry consequences far beyond this single case.

At its core, this is a federalism issue. The 10th Amendment exists to preserve the autonomy of states to enforce their own criminal laws through their own courts, free from coercion by national political figures. A state prosecution conducted under state law, adjudicated by state courts, and resulting in a lawful sentence is not supposed to be subject to veto by a ruthless strongman seeking to reward allies and intimidate opponents.

The power of the president to grant clemency is limited solely to federal crimes, for good reason. A power to intervene in this manner would amount to a presidential power to nullify state laws at whim.

If the governor caves under that pressure, the damage would not be limited to Colorado. It would establish a precedent in which state-level law enforcement becomes conditional on federal political approval. That is a profound erosion of constitutional law, one that should alarm anyone who claims to care about federalism or the separation of powers. That consideration is particularly acute now, when the Trump administration is waging an all-out attack on the powers of the states to be anything less than, as he audaciously claimed, his own “agents.”

Trump and his party already control all three branches of the federal government, but that is not enough. He has also set out to crush any degree of political independence in the states, particularly states whose voters tend to prefer Democrats, as is their right.

Worse still, a commutation or pardon for Peters would actively reward an ongoing campaign to encourage criminality in service of personal political power. Trump’s mass pardons and promises of clemency for those convicted for the Jan. 6, 2021 attack on the Capitol were not acts of reconciliation or healing. They were signals, unambiguously clear ones, that loyalty to him supersedes loyalty to the law, and that participation in attacks on democratic institutions will go unpunished if carried out in his name.

Commuting Peters’ sentence under these conditions would reinforce that lesson. It would tell future election officials that the risks of subverting democracy are mitigated if they align themselves with the right political patron. It would normalize the idea that election interference is not a grave betrayal of public trust, but a form of partisan activism eligible for retroactive absolution.

A democracy cannot survive that logic. Deterrence matters here because the stakes are existential. Elections are an arena where cheating cannot be tolerated without unraveling the entire system, and our constitutional republic is already more than frayed since Trump’s return to the White House.

Stand Firm for Law and Democracy

None of this is an argument against mercy in principle. We should always be willing to reassess punishment, particularly as people age and their circumstances change. A reasonable case can be made that America is too fond of excessively long sentences across the board, fueling our unusually high incarceration rate compared to other democracies. But compassion must be exercised with discernment, and clemency must not be confused with surrender.

In Tina Peters’ case, commuting her sentence would minimize the seriousness of her crime, disregard the tangible harm inflicted on her community, and reward a posture of unrepentant defiance. It would not reflect a general principle about criminal justice reform, but singling Peters out as special, as if she is uniquely deserving of favorable treatment. More dangerously, it would signal that political pressure can override lawful convictions, and that attacks on democratic institutions may carry political upside if undertaken on behalf of a powerful figure.

That is not compassion. It is capitulation.

If Colorado wants to defend the integrity of its elections, the independence of its courts, and the principle that no one is above the law, Gov. Polis should resist this temptation. Mercy has its place. But so does accountability. And when democracy itself is the victim, the balance between them is not close.

© The UnPopulist, 2026

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

Yes, we Coloradans have been pummeling Gov. Polis' office with letters, phone calls and emails telling him to NOT pardon that....(insert expletive here), she expressed NO remorse and said she would do it again. We - the entire WORLD - are so tired, exhausted and fed up with all of this MAGA crap! That being said, we still have to keep going and fight back at every turn or we will lose our democracy and possibly witness World War 3.

I hate to say this but he should not pardon her because it will give the appearance of a governor submitting to the corrupt behavior of the President. Had Trump kept his nose out of it and quietly advocated for her release on humanitarian grounds (if he REALLY cared) then the Governor MIGHT consider a commutation (not a pardon) Trump, by declaring her to be a victim of a political witch-hunt and demanding her release through threats and even claiming he can pardon her himself, has made the choice to pardon impossible. He could also put off the commutation until his last day in office in January 2027. But only on humanitarian grounds.