Let’s Not Grant the Postliberal Critique of Market Liberalism

Discontents with liberal modernity are perennial and a spiritual awakening won't cure them

Book Review

Nineteen-seventy was a banner year for American cultural criticism. Blockbusters like Charles A. Reich’s The Greening of America and Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock heralded a decade of introspection. Another bestseller, now largely forgotten, was by the American sociologist Philip Slater: The Pursuit of Loneliness: American Culture at the Breaking Point. (You can read the 1970 edition here.)

Why, Slater asked, is America so prosperous, yet so unhappy? “Scarcity is now shown to be an unnecessary condition,” he wrote. Americans enjoyed an unprecedented bounty of choice—a bounty not only of consumer goods but also of lifestyles. Yet prices were high, services were deteriorating, the environment was suffering. Worse, “there is an uneasy, anesthetized feeling about this kind of life,” Slater wrote. “We ... feel bored with the orderly chrome and porcelain vacuum of our lives, from which so much of life has been removed.” The blame, he charged, lay with an “old culture” which “has been unable to keep any of the promises that have sustained it” and “is less and less able to hide its fundamental antipathy to human life and human satisfaction.”

Revised in 1975 to reflect the end of the Vietnam war, Slater’s book made its way, by and by, into the hands of a certain teenager living in the suburbs of Phoenix, Arizona. At 16, I thought the book was brilliant. I wasn’t alone. The Pursuit of Loneliness fed into a stream of national self-doubt that culminated in President Carter’s “malaise” speech of 1979. The country, said Carter, faced a

crisis of confidence ... that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation.

In 1979, his diagnosis seemed right to me and a lot of other Americans.

And then ... Reagan. Morning in America. Disinflation. The collapse of the USSR. It turned out that America’s crisis had more to do with bad policy and bad leadership than with the American soul or the capitalist system.

Here we are 50 years later, and what went around has come back. On every side, critics scourge market capitalism and liberal democracy as exhausted, failing, obsolete. Slings and arrows fly from the pens of postliberals, post-modernists, radical feminists, queer theorists, National Conservatives, Christian nationalists, Catholic integralists, intersectionalists, techno-monarchists, aristopopulists, and out-and-out Fascists. Some of these people occupy positions of global leadership, and more are conniving to do so. They have little in common except their bad ideas and their hatred of liberalism.

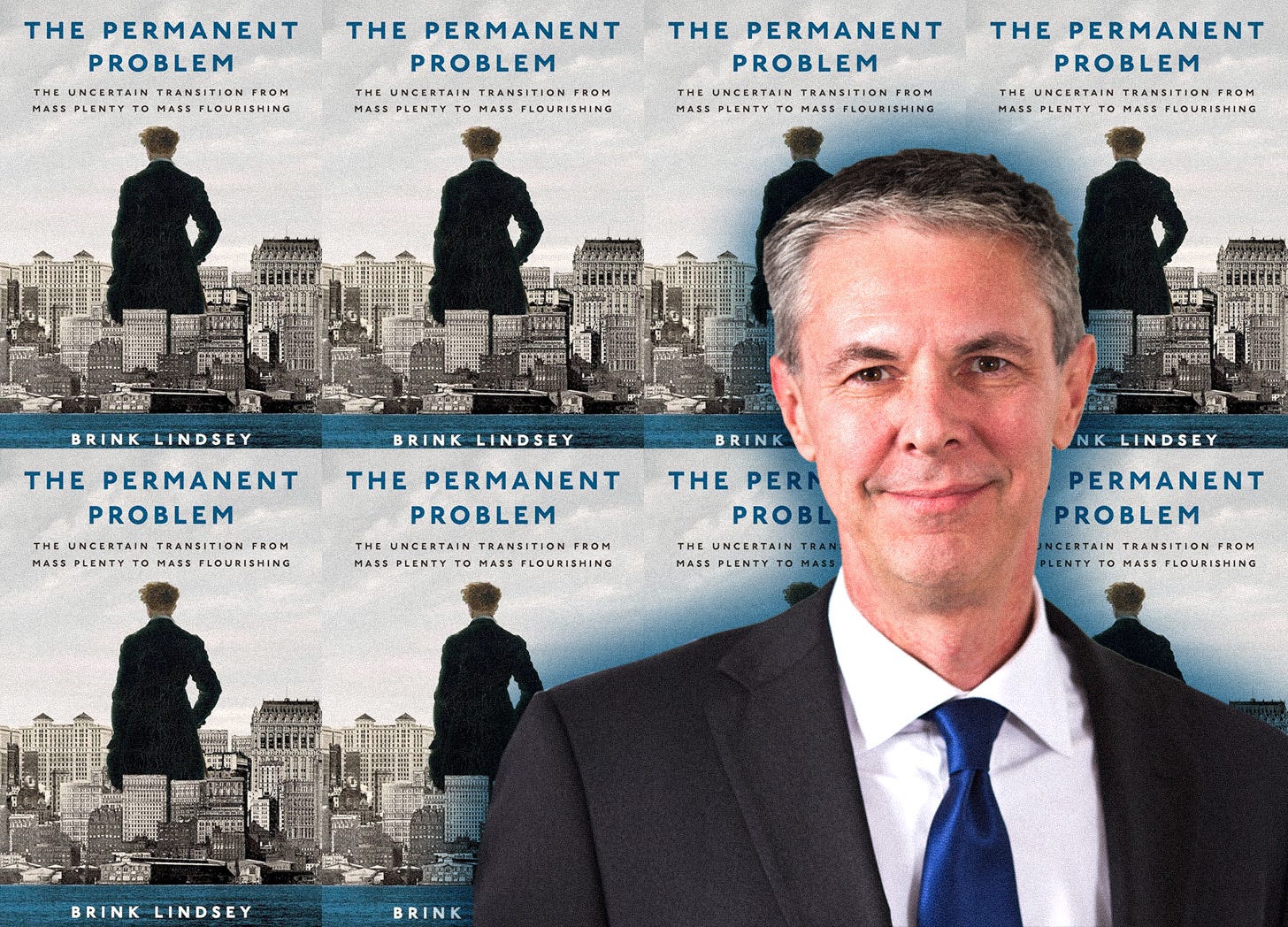

But today, as in the 1970s, some of the sharpest criticism—and certainly the most intelligent—comes from inside the house: distinguished liberal thinkers like Francis Fukuyama, William Galston, and James Davison Hunter. Arriving to join them is Brink Lindsey of the Niskanen Center, a Washington think-tank. Once a scholar at the libertarian Cato Institute, Lindsey remains within the liberal camp but has strayed from neoliberal orthodoxy. Just how far is apparent in his new book, The Permanent Problem: The Uncertain Transition from Mass Plenty to Mass Flourishing.

Lindsey begins with a famous challenge framed by the economist John Maynard Keynes in his 1930 essay “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.” “For the first time since his creation,” Keynes wrote, “man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem—how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.” Affluence, Keynes saw, would bring challenges as well as blessings. People would need to find purpose beyond working hard and making money. Keynes hoped that unprecedented wealth might revive non-material values. Freedom from want, he said, could set us free

to return to some of the most sure and certain principles of religion and traditional virtue—that avarice is a vice, that the exaction of usury is a misdemeanour, and the love of money is detestable.

Building on Keynes, Lindsey argues that mass plenty has arrived but mass flourishing and fulfillment have not. “Getting richer as a society is no longer reliably making us better off; indeed, the effect is rather the opposite. This is the nasty riddle that the permanent problem now poses for us.”

How nasty? The first seven of 10 chapters, and two-thirds of Lindsey’s 200 pages, consist of a litany of capitalism’s failures. We are overweight, screen-addicted, lonely, depressed, anxious; we are abandoning sex and marriage and the labor force and the two-parent family; we are dechurching, polarizing, class-dividing, depopulating, overparenting; and more, and still more. “To put it bluntly,” Lindsey says, “society is falling apart.”

Worse than all that—yes, it gets even worse—“capitalism is sociologically unsustainable,” “consumerism and managerialism admit no stopping point,” “proceduralism [has] run amok.” Bureaucratic rigmarole and a “dramatic complexification of the social order” alienate us from democracy and strip us of agency. Meanwhile, the very successes of capitalism allow corporations to become complacent, interest groups to impede progress, and individuals to become risk-averse.

If there is any criticism of liberal modernity that is not in Lindsey’s book, I couldn’t find it. Had I stopped reading after Chapter 7, I would take the book for a postliberal screed that outdoes anything by Patrick Deneen. But Lindsey is not going where the postliberals go. In fact, he is going where Philip Slater went.

Slater called for “the transition to and emergence of [a] new culture,” one that demotes individualism to a subordinate place in the American values hierarchy and prioritizes tradition, community, and relationships. He emphasizes that the new culture is needed to stabilize capitalism and democracy, not to overthrow them. Likewise, technology must be repurposed, not repudiated. “I do not want to put an end to machines, I only want to remove them from their position of mastery, to restore human beings to a position of equality and initiative.”

Slater thus seeks not a political revolution but a cultural one, a viral movement spreading from individuals and communities to the country and the world. “Nothing else will stop the spiraling disruption to which our old-culture premises have brought us.”

I had not thought about Slater for many years, but reading Lindsey, I couldn’t not think about him. At times I thought I might be re-reading him, so strong are the echoes.

“I fear that our present global monoculture system, with highly atomized populations that are heavily dependent on powerful states, is worrisomely vulnerable to both tyranny and chaos,” Lindsey writes. Instead of barreling toward this cliff:

we need to marshal capitalism’s capacity for technological and social innovation to develop new social arrangements that ease the strains of dependence on the impersonal system by supporting strong, functional face-to-face relationships.

In practice, by exploiting modern tech and tweaking regulations like zoning and occupational rules, individuals and communities can be empowered to do more for themselves. Zoom lets them learn and work at home, gigs and apps reduce their dependence on corporate jobs, online platforms let them source and trade goods locally, YouTube and 3-D printing let them build and fix their own stuff. Thanks to technologies like those, “instead of having to live close to work, more and more people can choose to live close to friends and loved ones.” There, Lindsey says, they can build “intentional communities” knitted together by common values and face-to-face interactions, a bit like the Orthodox Jewish community of Kemp Mill, Maryland, or the Catholic community of Front Royal Virginia. Greater independence from corporate drudgery and the mass market, Lindsey believes, can refocus life on face-to-face relationships, re-anchor us in the “physical world,” “rekindle ... the romance of the frontier,” and rewire capitalism for “abundance at human scale.”

Lindsey realizes that his techno-Jeffersonian vision (my term, not his) might be a minority taste, at least initially. But he hopes that a “pioneer archipelago” of adopters might spark what modern capitalism really needs: “something like another great awakening—a spiritual movement to lead our wayward society back to neglected truths and abandoned virtues.” Failing that, self-contained communities would provide alternatives for those who feel alienated and dispossessed in today’s system, reducing the demand for authoritarianism and anarchy.

Well. While modern capitalism certainly has its problems, I do not believe it is destroying itself, that “society is falling apart,” or for that matter that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation,” per Thoreau in 1854. (People have been worrying about the soul-destroying aspects of modernity for a long time.) If I did believe that society is falling apart, I would not believe that “intentional communities” and “pioneer archipelagos” could realistically solve the problem. When I read Lindsey saying his ideas are “potentially civilization-rescuing,” I see rhetoric that has gotten carried away with itself. When I reached his call for “another great awakening—a spiritual movement,” I wrote in the margin: “Good grief!”

Still, The Permanent Problem is worth your time. If you mentally dial down its excesses, you will find ideas that might measurably improve the quality of modern life, which is nothing to sneeze at. And we need more, not fewer, liberal thinkers to tackle the challenge of imagining new and hopefully better directions for the liberal project. We have plenty to fix!

There is a broader point to be made here about Lindsey’s book—and about Philip Slater’s. Only one economic, political, and epistemological tradition generates (or for that matter tolerates) intense, introspective criticism of itself. That tradition, of course, is the liberal one. Is Lindsey’s hoped-for spiritual movement likely? Probably no more than Slater’s now forgotten “new culture.” Yet both writers put their finger on real problems, push liberals to confront real failings, and seek to stretch the liberal imagination. And both remind us that liberalism’s secret weapon is its capacity for constructive self-criticism—something its competitors can never replicate.

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

Brilliant takedown of the recurring apocalypticism in liberal critcism. The parallel to Slater's 1970s anxieties really nails how these "civilization is ending" framings come in cycles, usually right before the systme adapts. I've noticed this pattern in tech policy debates too where everyone panics about disruption until markets and institutions figure out guardrails. The self-critique capacity argument flips the whole postliberal narrative on its head.

The problem with this is all the unexamined assumptions involved in treating "markets," "liberalism," "capitalism," and "neoliberalism" as interchangeable. Markets are at least as old as the riverine civilizations.

Capitalism and the wage system were created in early modern times in close alliance with the absolute state, and relied heavily on land enclosure and state-imposed labor discipline for their creation.

Neoliberalism is a project just a few generations old, and relies heavily on states to create artificial comparative advantage via protectionist enclosure by draconian IP accords and massive subsidies to extended logistic chains.

A market economy simply requires allowing market-clearing prices to form without hindrance, regardle of the prior definition of property rules. Capitalism, as a system of rent-extraction -- and even more so neoliberalism -- requires a specific form of property rules, centered on what Polanyi called "fictitious commodities." In particular, it requires property rules that create artificial abundance of land and resource inputs, and artificial scarcity of information and technique.