Why Is the American Experiment in Trouble? Simple: A Demagogue Has Ignited the ‘Dark Passions’ of the People

Liberalism’s real failure is that it assumes far too sunny a view of human nature, three recent books suggest

Book Review

Here in liberal land, we bang our heads against the wall, incessantly asking ourselves the same question: How could it have happened here? Donald Trump and his semi-fascist MAGA movement seem like invasive transplants from Europe’s bloodlands. How could they take root in American soil?

Perhaps, though, we were asking the wrong question all along. Perhaps the right question is why it did not happen sooner. Or perhaps the right question is: Why does it ever not happen?

Yes, liberal democracies face challenges and turbulence. Yes, liberal institutions are flawed and can fail. Yes, migration, crime, cost of living, offshoring, social media; yes, yes, yes, and also, frankly, blah, blah, blah, because the truth is that no shortcoming of liberal institutions or concatenation of stressors accounts for the specific appeal of a politician who admires foreign dictators, encourages an insurrection, claims unlimited powers, compares his opponents to vermin, treats the state as his personal property, lies, bullies, threatens, and—need I go on? In 2024, knowing full well what it was doing, and presented in the Republican primary and the general election with many alternatives who did not embrace semi-fascism, the American electorate chose Donald J. Trump.

To understand this reality, perhaps we liberals need to question our idealism about human nature and our romantic notions of American democracy. In their different ways, three books—two of them, I believe, landmarks of contemporary political thinking, and the third adding an intriguing psychological twist—force us to gaze into ourselves.

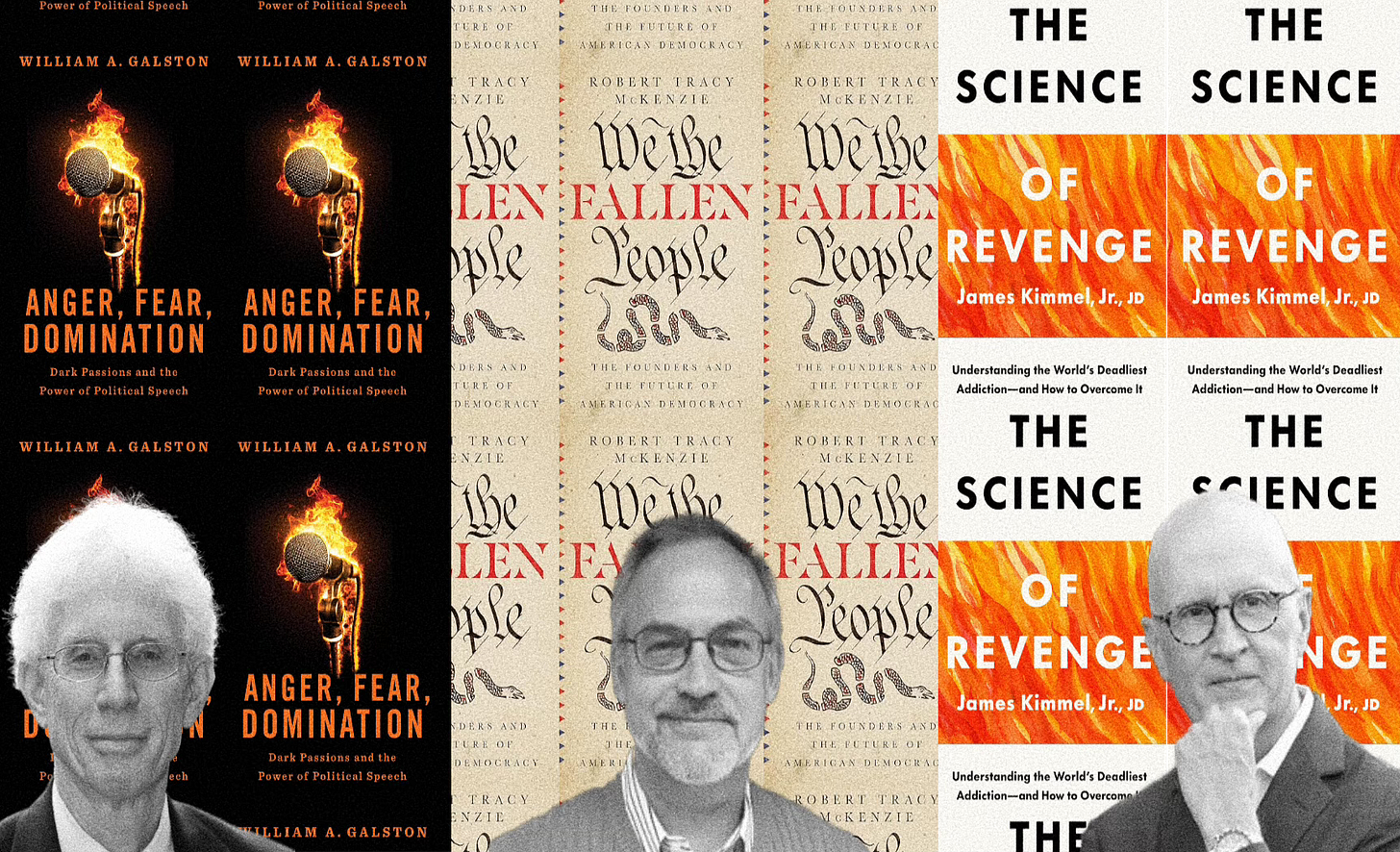

William A. Galston’s Anger, Fear, Domination: Dark Passions and the Power of Political Speech is a masterpiece, full stop. No one else could have written it. Galston is a colleague at the Brookings Institution and a personal friend, and I offered suggestions on his manuscript, so I do not pretend to objectivity. Please, judge for yourself. (The book is only 135 pages, so no excuses, just read it.)

If Aristotle and George Orwell had a baby, it would be this book. Combining the philosopher’s lucidity with the essayist’s realism, Galston centers something Aristotle and Orwell both well understood: political rhetoric does not merely reflect a democracy’s character, it also shapes it—and can distort, corrupt, and even destroy it. “The ability to put persuasive speech in the service of domination has been, and remains, the greatest threat to democracies,” writes Galston.

He builds his case on the bedrock of human nature. “Rational self-interest does not always drive human events, the passions matter, and evil is real,” he writes. “The dark side of our nature is here to stay.” He proceeds to plumb what he calls the dark passions: anger, humiliation, resentment, fear, and the drive for domination. Each has its peculiar pull, and together, in the hands of the gifted demagogue, they electrify mass audiences. “In mass politics, rhetoricians who can turn disconnected individuals into manifest communities with a collective purpose are enormously powerful,” observes Galston. “Unscrupulous orators know how to exploit this drive by enabling people who feel weak individually to experience power collectively, and then to use this power to dominate the groups against whom the demagogue directs them.”

Although Galston’s analysis is timeless, the main reason you and I care is that it happens to fit Trump like a glove, as Galston immediately recognized. “When I watched a Trump rally for the first time, my first response was horrified fascination,” he writes. “But this quickly gave way to the realization that I was watching democratic politics in its purest form—a man using speech to mobilize a multitude to act as he wishes them to.” Galston describes Trump’s 2023 CPAC speech as “a master class in the mobilization of the dark passions to advance a political agenda.” Trump conjures threats, whips up fear, voices resentments, blames sinister forces, and then offers himself as vindication. “For those who have been wronged and betrayed,” Trump declares, “I am your retribution.”

If you’re like me, you had trouble believing, at least initially, that anyone could fall for such obviously manipulative claptrap. Like a lot of liberals, I thought: seriously? I believed that the large majority of Americans are too discerning and decent to be swayed by dime-store demagoguery.

Alas, we liberals were woefully naïve, and our complacency left us defenseless. “Too often, liberal optimists are blindsided by ambitious leaders’ ability to mobilize the public’s anger, humiliation, resentment, fear, and desire to dominate, and to turn these qualities against liberal democracy itself,” Galston writes. “Today’s defenders of liberal democracy must set aside their illusions about human nature and history.”

One group of American liberals would be disappointed but not at all surprised by the country’s susceptibility to demagoguery. After all, they tried to warn us and—insofar as they could—protect us. The Founders were quite without illusion about the human passions, and they were distinctly unromantic about the American democratic character. “Although we may not like to hear it, proponents of the Constitution repeatedly insisted that, when it comes to our character, Americans aren’t exceptional,” writes Robert Tracy McKenzie, a professor of U.S. history at Wheaton College. “Hamilton was characteristically blunt: ‘We have no reason to think ourselves wiser or better than other men.’”

The quotations are from McKenzie’s 2021 book We the Fallen People: The Founders and the Future of American Democracy. No points deducted if you missed it; the book received little notice when it came out, perhaps because it emanated from a Christian publisher, perhaps because in 2021 Trump seemed safely in the rearview mirror, and perhaps because sometimes seminal books get overlooked.

Make no mistake, however: like Galston’s, McKenzie’s book is a landmark of liberal self-understanding. Indeed, they should be read in tandem. McKenzie meticulously documents how the founders’ view of human nature comports with the Christian concept of fallenness. “For all their praise of virtue, the Founders were realists,” he writes. “They exhorted Americans to revere and practice virtue. They didn’t expect it. When it comes to gauging their reading of human nature, we must see that they thought of virtue as, quite literally, artificial. It doesn’t occur naturally in our species.”

Now, the Founders also did not assume that humans are relentlessly depraved. They saw virtue as attainable, but rare and in need of studious cultivation by citizens and civil society. “The mild voice of reason,” as Madison put it (in The Federalist No. 42), “is but too often drowned ... by the clamors of an impatient avidity for immediate and immoderate gain.”

Of all the threats the Founders perceived to America’s democratic self-government, the demagogue was what they feared most. Hamilton says it starkly in Federalist No. 1: “Of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics, the greatest number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants.”

And yet—in only two generations, Americans dismissed and then forgot the Founders’ warning. Andrew Jackson and his supporters ascended by flattering the people that they are good and wise, and by claiming that the president personally embodies the public’s goodness and wisdom. “At the heart of the Jacksonians’ appeal to the voters in 1828 was not a set of specific policy proposals or a careful comparison of the candidates’ qualifications,” writes McKenzie. “Above all, they offered the voters a larger story in which to situate their lives. Its central themes were grievance, conflict, corruption, and conspiracy.”

Ever since, to a greater or lesser but always considerable extent, the United States has been Jackson’s country more than Madison’s. “As it emerged in Jacksonian America, the gospel of democracy is that men and women individually are basically good, and collectively they are reliably wise, with the result that the will of the majority is infused with an unassailable moral authority,” writes McKenzie. Woe betide the politician who dares to hint that sometimes the people are not as wise as career politicians, elite experts, or professional administrators.

Nonetheless, party gatekeepers, establishment media, institutional safeguards, and politicians’ respect for certain norms sufficed to fend off demagogic attacks until 2016, when the establishment bulwark faced, and crumbled before, precisely the kind of person Hamilton warned against in 1792 as “the true artificer of monarchy”: “a man unprincipled in private life, desperate in his fortune, bold in his temper, possessed of considerable talents ... known to have scoffed in private at the principles of liberty.”

Among the demagogue’s tools, none is more powerful than the motivating power of revenge. As Galston notes, the desire for revenge can and often does override rational self-interest; and it can and often does “turn brutal and end by denying the adversary’s humanity.” For a mob in thrall to vengeance, anything goes.

Why? Perhaps because, as James Kimmel Jr. argues in The Science of Revenge: Understanding the World’s Deadliest Addiction—and How to Overcome It, the impulse to seek revenge is hard-wired and literally addictive.

Kimmel, a lecturer in psychiatry at Yale University (no relation of Jimmy Kimmel), describes himself as a former revenge addict who, first as a litigator and eventually also as a husband and father, “threatened retribution against just about anyone for the slightest offense.” Eventually, his escalating cravings for revenge brought on self-loathing, depression, and suicidality, which in turn led to self-awareness and a reset—plus a desire to learn everything he could about revenge.

“Your brain on revenge looks like your brain on drugs,” he writes. “Getting revenge, or even just fantasizing about it, is rewarding, releasing dopamine and activating the brain’s pleasure and reward circuitry.” Let’s face it: revenge feels awesome! But, like other highs, it wears off. We crave more. The spiraling desire for vengeance may become self-harming and self-defeating, but no matter: “Revenge destroys individuals, families, romantic relationships, fortunes, communities, nations, and empires.”

The world’s great religions can all be viewed as being, among other things, elaborate moral and social technologies designed to cabin and channel the craving for revenge. “Vengeance is mine,” decrees the god of Judaism and Christianity (in Deuteronomy and Romans); that is, revenge is God’s province, not ours. Our constitutional order relies on a similar principle: revenge is the law’s province. Had retribution been left in the hands of ordinary individuals, families, and tribes, a modern liberal society would be impossible. (Ask an Iraqi.)

You see where this is all leading. “Donald Trump’s long history of uncontrolled vengeful behavior suggests he’s suffering from revenge addiction,” writes Kimmel. Trump has made revenge the organizing principle of his career. He nurses every grievance, real or imagined, and exacts revenge in the pettiest imaginable ways. He comes right out and says it: “I am your retribution.”

Kimmel does not muse on this question, but it naturally arises: what if, after a decade under Trump’s influence, American politics has become not only accepting of revenge as a motivating principle but positively addicted to it? What if WWE-style revenge porn has become, for many Americans, the point of politics? And what if, the more revenge-saturated our political culture becomes, the more revenge-hungry it becomes?

Most Americans do not want to turn politics into hunger games. Polls show that most Americans want politicians to squabble less and deliver more. But if a revenge-addled minority can take over one of our political parties and dominate sectors of the media, it can cause enough disruption to make ordinary politics dysfunctional. As Galston writes, “When the dark passions dominate politics and social relations, comity erodes, and enmity, vengeance, domination, and dehumanization come to the fore. Decency is thrown on the defensive, and liberal democracy—which, more than any other form of government, requires restraint and mutual forbearance—becomes hard to sustain.”

Well. Before we all jump off a cliff, let us remind ourselves: the dark passions are not the only passions. Demagogues are not the only political actors. Generosity and decency, lawfulness and truthfulness, and what Lincoln called “fraternal feeling” all still matter. Kimmel notes that, against revenge addiction, forgiveness really works, because it “appears to reduce the pain of grievances and the desire for revenge rather than just covering it up.”

Galston likewise notes that meliorating rhetoric has its own power, citing, among other examples, Robert F. Kennedy’s impromptu April 1968 speech in Indianapolis, where he calmed an angry crowd after Martin Luther King’s assassination. Leaders who perceive and regret the country’s descent into retributive politics—and there are many—can find their voices.

We need to hear more from them, much more, especially from those who are Republicans. “We must ‘fight fire with fire,’ passionate advocates insist,” writes Galston, “and there is, I confess, an exhilarating sense of release when we do. But ... it is usually more effective to fight fire with water. Responsible leaders should seek to douse the flames and cool the temperature of our politics.” History has shown that the dark side can be defeated. But to defeat it, our leaders—and all of us—must push back; and to do that, we must heed Galston’s grim warning about its power.

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

I ran across the Galston book over the weekend, watched the Brookings youtube interview with Galston and Rauch, which was excellent. I'm one chapter in, and loving it. IMHO, it is absolutely the right diagnosis. I think it aligns closely with James Baldwin's thesis as well. I was planning to recommend the book to the Unpopulist to review, and you were miles ahead on this. Thank you for this! Highly recommend.

A wonderful handful of book summaries! As a conservative I have never had much faith in human nature. A skepticism only reinforced the longer I live. Maintaining a Stoic perspective keeps me from falling into cynicism and nihilism.

The Republican vision of a permanent Republican majority began to gain traction with the election of 1992 when Bill Clinton was sworn into office. The mid-term election of 1994--- which was the first public relations campaign based on a national party propaganda piece called "The Contract With America." Newt Gingrich understood that as long as Tip O'Neill's adage about all politics being local prevailed Republicans could never get the power to dominate the government. Like Trump's "Project 2025" the Contract was formulated by The Heritage Foundation. Only 13% of the Contract's promises were ever met. "Project 2025" has been much more successful.

The Democrats in response also began to increasingly nationalize their campaigns. From then on forward the only thing that mattered was securing a chamber majority and negotiating (compromising) with the other party as little as possible if at all. The goals of both parties became dis-empowering the other. Voters had to hate and distrust one or the other of the parties. The acrimony increased into the hyper-partisan revenge fest we see today.

The 21st Century National Socialists in ascendancy today see their primary purpose to permanently dis-empower what they call "The Left." "The Left" is an elastic term which basically includes anyone who questions or tries to challenge whatever their agenda is on any given day. Conservative firebrand Liz Cheney is "left." John McCain is "left." Mitt Romney is "left." and so on so forth blah, blah, blah. All of which is intellectually dishonest and irrational but a simple and convenient way to dispose of any meaningful engagement with ideas dangerous to the "inner party." Just call it "woke" and pay no more attention to it.

The goal of the election of 2024 is to dis-empower the Democratic Party permanently at the federal level and in the states where they currently hold absolute power. But even if they fail, even if the Democrats were to win back a slim majority in the House and Senate they will still be stopped by Trump's veto power and The Republican Supreme Court. The Democrats will never have the power to undo the damage that has been done in two years without winning every general and mid-term election--- for at least a decade. And probably not without a demagogue of their own.

Recovery from rage is possible. However the people who need recovery most will, like their alcoholic brethren, deny they have a problem. They also get too many benefits from their rage