William F. Buckley Cemented the Conservative Movement’s Preoccupation with the Liberal Enemy

He couldn’t define what conservatism was, just what it wasn’t

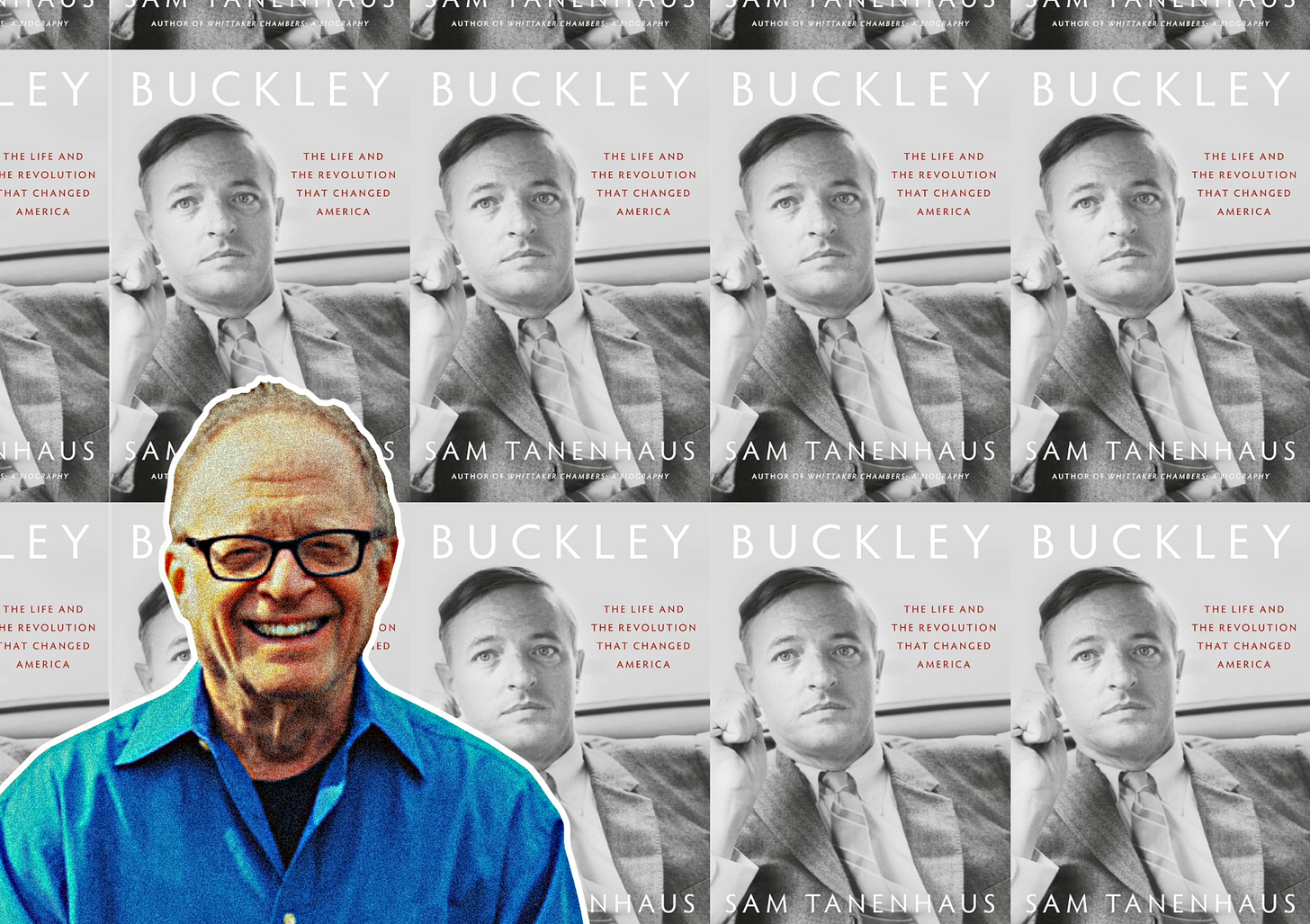

Book Review

From the early 1950s until the close of the millennium, William F. Buckley Jr. stood out as America’s preeminent conservative. The term “influencer” would be anachronistic, but Buckley was a leading conservative light on every platform of the day. He made his bones as a speaker, magazine founder, editor, television host and personality, novelist, journalist, and pioneering opinion writer. He became a counselor to presidents and was unquestionably one of the leading builders of the postwar conservative movement. Over the decades, Buckley moved from enfant terrible of the “liberal establishment”—by which he meant the dominant political ideology of New Deal liberalism and the social caste that ruled it—to something more like a lion at a zoo. Still fearsome, but comfortably ensconced in the halls he once castigated.

Ten years before his passing in 2008, Buckley bestowed on Sam Tanenhaus, a historian, the honor of being his official biographer. This week, Tanenhaus made good on that promise with Buckley: The Life and the Revolution that Changed America. In his thousand page effort, Tanenhaus gives us a many-faceted Buckley. But two distinct public personas emerge: the ideological firebrand and the comic patrician. This combination of serious and unserious, rigid and flexible, resentful and playful, rescued the American right from itself, Tanenhaus argues, especially following the disaster in which Lyndon Johnson buried the conservative favorite son Barry Goldwater in the 1964 presidential election.

The Pseudo-Aristocrat

Tanenhaus is an accomplished biographer; his Whittaker Chambers, a Pulitzer-finalist in 1998, is remarkable. But Whittaker Chambers’ life had a neat narrative arc. What do you do with Buckley? Recall that Buckley wrote a full book covering just a single week of his life. Twice. So Buckley is necessarily long, but it moves fast, propelled by Tanenhaus’ prose, his jeweler’s eye for fine detail, and the frankly incredible episodes he includes.

More than that, Buckley is a vantage point for understanding substantial parts of the post-World War II right—including up to the present. Buckley’s story intersects negatively with the Civil Rights Movement. Tanenhaus charts his shift from a Catholic, libertarian aristocrat to spokesman for the “forgotten American” and a conservative white majority—a trajectory Buckley himself only recognized slowly. In finding this audience, the intellectual and political vanguard Buckley played such a key role in assembling transformed itself and America.

Tanenhaus delves deeply into Buckley’s childhood and family. He convincingly finds the early Buckley’s ideological and personal origins in his youth. As the anarchist writer Karl Hess explains, Buckley is “a Catholic aristocrat of the Spanish persuasion.” His parents curated his childhood to make that aristocratic life as close to reality as possible. The large Buckley clan were more than a family. They were a self-contained culture—hermetic, appealing, and drawn to beauty. Sylvia Plath is in their orbit.

That is, until they crossed into the deep prejudices of the era. Then the children are reactionary pranksters set against the world. They burned crosses and defaced an Episcopal Church in an episode laden with accusations of antisemitism. Buckley himself wasn’t involved in either case—but his father’s antisemitism ran deep. Later, Buckley Senior prevailed on Buckley Junior to break up a relationship between one of his sisters and a Jewish man—a friend of Buckley’s. Proving more loyal to his father than to his sister (or friend), Buckley did just that.

Tanenhaus suggests Buckley came by his elitism, his sense of white supremacy, and with it, noblesse oblige, honestly. He learned from his father’s Texan and Mexican sojourns to disparage democracy and hate revolution. Tanenhaus is superb on the racially complex town in South Carolina where the Buckleys are fondly remembered, but whites maintained the idyll through violence.

Tanenhaus reveals Buckley’s father funded an upstart paper founded in 1956 to oppose integration. The Buckleys were its sole backers, and Buckley’s sister and close working associate, Priscilla, even appeared on its masthead. All involved took knowledge of the paper to their grave. From this South Carolinian vantage point, Buckley recognized the possibilities of an alliance between the Republican right and Southern whites 15 years before Richard Nixon’s infamous Southern strategy.

Buckley was a teenaged America Firster and ready debater. It’s at Yale, though, where he was the biggest man on campus in a bumper class—a debate champ, Bonesman, and editor of the Yale Daily News—that Buckley’s life went into overdrive.

God and Buckley at Yale

As editor of the school paper, Buckley harangued faculty he thought religiously irreverent or economically socialist. He was a young reactionary on the make and eager to poke the administration. But, Tanenhaus says, Buckley sensed something meaningful in Yale’s reaction to him that led to his career-making God and Man at Yale. As an institution, Yale was anti-Catholic, maintaining unspoken quotas limiting Catholic and Jewish student enrolments. Yale stood in not just for elite education, but hypocritical liberals everywhere.

What Buckley learned at Yale was that the American right’s real enemy was the “liberal establishment.” (Sound familiar?). Liberals, for Buckley, were “far more dangerous” than radicals, socialists, or communists. To Buckley and his growing readers, liberals got hysterical when their unexamined orthodoxies were questioned. For their openness, liberals deplored all hypocrisies except their own. From these premises, Buckley made a career.

Next, Buckley and his old debate partner and brother-in-law Brent Bozell put together a defense of Joseph McCarthy. Bozell typically gets cast as a tragic sidekick, a hardliner, or a pseudo-martyr for postliberalism. But Tanenhaus unexpectedly highlights Bozell’s centrality as a prescient strategist of the conservative movement. He comes into his own as Buckley’s debate foil, but also his intellectual one.

Buckley and Bozell didn’t think McCarthy a first-rate statesman. Nevertheless, their early careers were deeply entwined with him. Indeed, Buckley maintained a policy that wasn’t quite “no enemies to the right,” but came perilously close as he worked to maintain the largest possible anti-liberal coalition that necessarily included conspiracists and racists.

Intellectual Comedy

Buckley is typically considered a conservative intellectual. After all, he wrote dozens of books and debated hundreds of academics and writers. But, Tanenhaus rightly argues, Buckley was never really a theorist or deep thinker. He believed in ideas, but it wasn’t his calling to plumb them. Despite several serious efforts, Buckley never wrote his “big book.”

Instead, Tanenhaus gives us Buckley as a political performer. His genius was “intellectual comedy.” His best mediums were speeches and television, his spoiler mayoral campaign in New York, the (quite good) book he got out of the campaign, and his self-referential books in general. Buckley mastered the smirk, the pointed query, the sigh, the quip, the passive-aggressive introduction. Even his voluminous columns were a chance to perform. To be sure, Buckley was very smart, but he excelled from an early age at sounding deeper on a subject than he actually was. Even his aureate prose was performative: a “preemptive smokescreen,” one protégé put it. There had always been polemicists and cranks on the right. Someone finally made it look fun.

Buckley’s other contributions to the American right were as an institution builder and totem. In many ways, Buckley’s real life’s work was National Review. The magazine served as a platform to attack liberals and liberalism—words he and his fellow conservatives warped out of recognition—and to some extent hash out what exactly conservatives stood for. Over time, Buckley learned how to drive the news, not just comment upon it.

With National Review, and later his television show Firing Line, Buckley could bestow a degree of respectability. As a gatekeeper, Buckley could exercise some constraints over the right. But only so much. In addition to his own coalitional instincts, Buckley had subscribers and donors to satisfy, voters to win, and colleagues to mollify. His tense relationship with the conspiracist John Birch Society demonstrated the limits of Buckley’s powers as arbiter of conservatism. Despite disliking the organization and its founder, Robert Welch, Buckley pulled his punches and alibied the society—although not always Welch—for years.

Buckley often considered himself a libertarian, but he reliably supported U.S. security services. Tanenhaus depicts the student Buckley dissembling to defend the FBI on campus. It proved habit-forming. The mature Buckley gave cover to the under-fire CIA. Likewise, as a journalist he wittingly or not advanced Nixon’s anti-Allende policy in Chile and—Tanenhaus hints—maybe used psychological warfare techniques to distract during the Pentagon Papers scandal.

Tanenhaus reveals that Buckley knew more about Watergate than he let on. Previous biographers have put Buckley’s ambiguous actions during Watergate down to pained indecision. Tanenhaus argues that his statements in defense of the administration amount to being an “accessory after the fact.”

Cruising Speed

Buckley’s big idea, though, is a variation of the one he picked up at Yale. There is, he believed, a “liberal establishment.” It’s barely cognizant of its own existence—but it imposes a rigid, equalitarian, soft-headed orthodoxy on the rest of America. Instead of joining this elite, Buckley—a product of his truly unique upbringing—spent his career trying to expose and dismantle it and the world it made, wielding every idea or news story as a cudgel. Or so it seemed.

Tanenhaus winds up the main narrative of Buckley by 1980. Buckley’s peak radicalism ran from 1951 through to the late 1960s. During this period, he shocked liberals, launched a defining magazine, cheer-led a presidential campaign, became the most widely syndicated columnist in America, ran for mayor of New York, and earned a television show. Gradually, Buckley’s libertarian orthodoxies fall away and he took on his most successful role: the patrician defender of the silent white majority’s prejudices.

But Buckley is also a story of a radical joining the world he once sought to remake. Buckley became an institution. In his institutional era, Buckley received the legitimacy he perhaps craved. He became a regular in The New Yorker. His circle of friends encompassed moderate and liberal journalists and intellectuals. Henry Kissinger, whom Buckley had introduced to Richard Nixon, now cultivated Buckley for the Nixon Administration. The one-time scourge of the GOP became a clubby part of the gang. By the time Reagan’s in the White House, Tanenhaus writes, Buckley was “not so much in a bubble as in a luxuriously appointed helium balloon.”

By collapsing the last 30 years of Buckley’s life, Tanenhaus only deals cursorily with significant rumbles, left and right. It’s probably the correct decision, but we get only glimpses at, for instance, Buckley’s tortuous struggle with right-wing antisemitism in the early 1990s. In other places, one might quibble with the balance of coverage. Perhaps there could have been more on the inner workings of National Review, which demanded so much of Buckley’s professional life. Tanenhaus gives us a strong portrait of Buckley’s devout Catholic faith. But it’s such a bedrock for Buckley’s life and politics that it may have necessitated greater analysis than there is. The relationship with James Burnham, a political theorist who became one of Buckley’s most important mentors and lieutenants, deserved more detail. We learn very little, too, about Buckley’s relationship with his wife and son. Although, knowing the way Buckley’s son and literary executor Christopher threatened to cut off Tanenhaus’ access to Buckley’s papers—as presented in the younger Buckley’s beautiful memoir Losing Mum and Pup—one wonders whether this decision was out of Tanenhaus’ hands.

Did Buckley Give Us Trump?

Buckley is likely to be the definitive biography. If you want to damn Buckley, there’s plenty of ammunition—not least of all his efforts to free Edgar Smith, a convicted and obviously guilty murderer and sexual predator, from prison. Released, he attacks again, though, mercifully, no one is killed.

Yet alongside Buckley as ideologue and patrician runs a third persona. The magnanimous friend; the “boon companion.” This was Buckley at his best. Tanenhaus presents a surfeit of quotes attesting to Buckley’s charm, generosity, bonhomie, and joie de vivre.

Tanenhaus concludes that, in Buckley’s time:

as in our own, no one really could say what American conservatism was or ought to be. Buckley himself repeatedly tried to do it and at last gave up. But for more than half a century, millions of Americans could confidently say who had been the country’s greatest conservative, William F. Buckley, Jr.

This is correct. It’s hard to define a coherent, consistent, timeless idea of conservatism. Many—not just Buckley—have tried. For a time, Buckley reconciled the competing aspects of the American right in his own person: its individualist libertarianism, fervent religiosity, faith in the free market, hawkish anti-communism, base disdain for liberals, and populist demagoguery. But also its knotty relationship with racism in the segregated South and Northern cities and suburbs; its heritage of antisemitism; its complex relationships with conspiracist cranks and authoritarians; and the deliberate or convenient forgetting of these darker elements. None of these aspects are unique to Buckley, but he singularly embodied them all.

As a conservative, Buckley had a laundry list of “principles” that often sat in tension with one another. Like other conservatives, Buckley rolled his principles out strategically rather than consistently. Whatever principle was most relevant for the political issue at hand suddenly became the most apt, the most important.

Tanenhaus doesn’t make the claim that Buckley built the American right. But for a long time, Buckley represented something like its figurehead, patron saint, and paladin all at once. Activists and intellectuals looked at Buckley as their ideal.

And what has that bequeathed us? A right that takes liberals as traitors to America. That prioritizes performance and controversy over principles. That hides its historic dalliances with white supremacy. That reflexively defends the punitive power of the state. After all, Buckley bestowed his blessings on the likes of Rush Limbaugh, Dinesh D’Souza, and Laura Ingraham, all architects of the present moment.

Yet, this doesn’t quite do Buckley justice. For his limitations as a theorist, Buckley really did care about ideas, and the right reasons behind his positions that the crass hyper-culture warriors lack today. Buckley’s idea of “owning the libs” meant wit and debate. He put liberals and radicals on television for prolonged discussion; he didn’t caricature them on political talk shows.

Buckley’s halting efforts at policing the cranks in his own party are overstated, but they were real and generally pursued in good faith. Buckley cared about marshalling responsible conservatives and maintaining respectability, an idea that seems quaint today. As the conservative archetype, Buckley put a premium on ideas and high culture, not instinctive vulgarity. He exhibited spiritual and financial generosity, not a get-mine parsimoniousness. Above all, Buckley, especially in his mature years, demonstrated a vital forbearance and friendship for political foes (Gore Vidal notwithstanding) absent from the media complex he inspired.

But, we live, to a not inconsequential degree, in a world Buckley has shaped—and there is much to lament about that.

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

Thanks for the piece. Since my parents never paid for cable TV growing up, PBS was a mainstay. My political awakening began with the McLaughlin Group and Firing Line. But I had very little knowledge of Buckley other than his accent and mannerism made me wonder if he was American when I was a kid. Obviously, the conservative movement became a grift/entertainment industry the last 30 years. Finally in one fell swoop, destroyed itself completely by letting Trump hijacked it a decade ago.

Been waiting for Tannenhaus to publish for so long, I can't remember if I pre-ordered this.