The Censorship-Industrial Complex: The Right’s New Boogeywoman

Renée DiResta describes how a loose coalition of influencers mobilized on social media and targeted her for the crime of flagging lies and misinformation

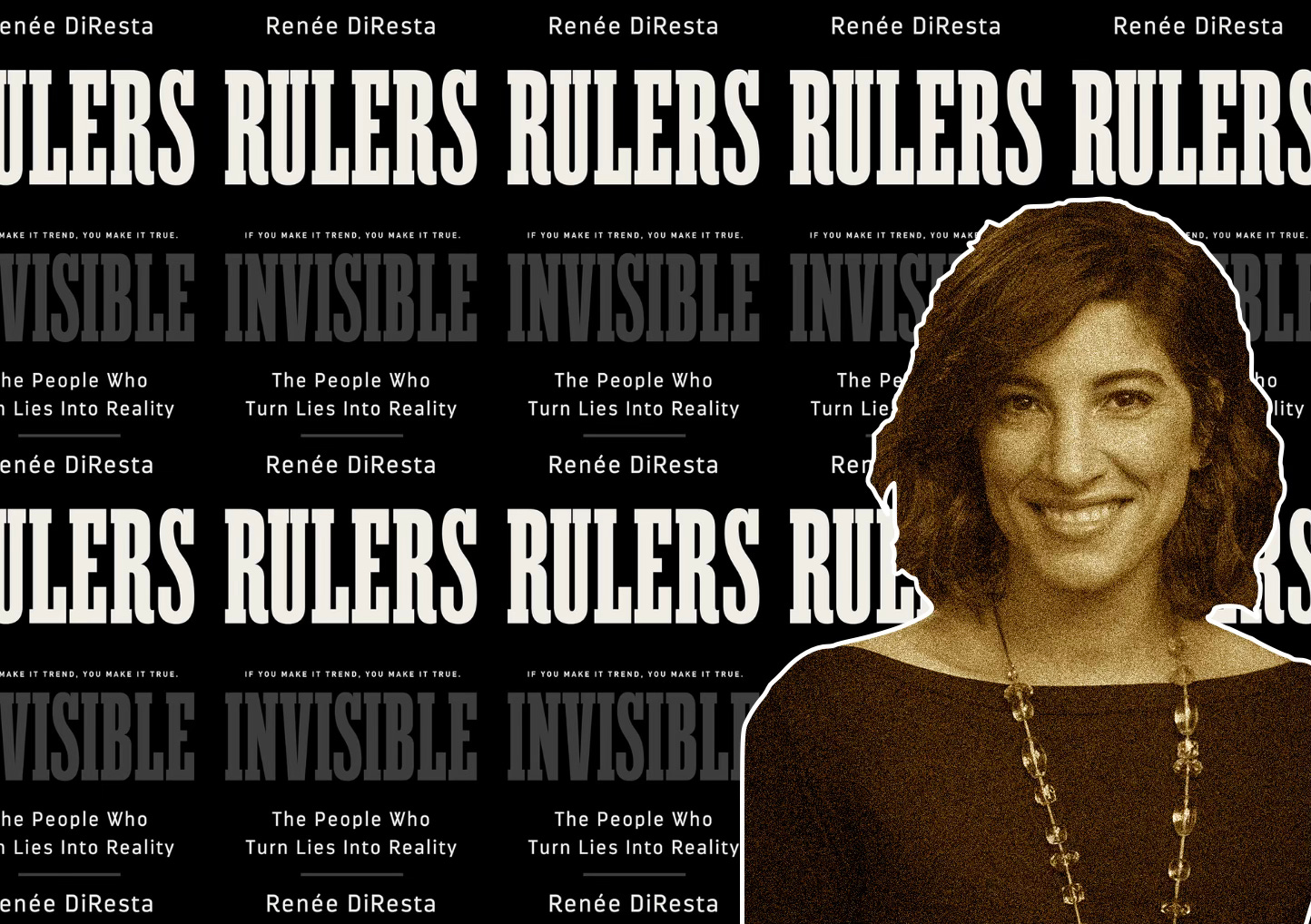

Book Review

How—how in the world—could it have happened? How did what seemed the most unambiguously good technology of our lifetime turn into the most abused and abusive? And not gradually but, in the scheme of things, practically overnight? Everyone over 40 remembers the boundless promise of digital media and online connectivity 25 short years ago. It would bring us together in exciting new concatenations of creativity and community; make reliable information about everything available instantly; bring a windfall to newspapers by cutting printing and distribution costs; expand the marketplace of ideas to turbocharge progress toward truth.

Well, we got some goodness. And also a boatload of badness: trolls, edgelords, mass disinformation, rampant misinformation, mimetic warfare, alternative realities, addictive algorithms, radicalizing recommendations, fake news, fake persons, canceling and bullying and doxing and dragging and brigading and many other previously nonexistent verbs. Also we got news deserts, depressed kids, and Q-Anon, plus Alex Jones and Yevgeny Prigozhin, characters not even “Get Smart” could have dreamed up.

All technologies have their dark side. Yet the dark side of the interwebs has come to dominate public conversation to a remarkable, and largely justifiable, extent. In her important new book, Invisible Rulers: The People Who Turn Lies Into Reality, Renée DiResta persuasively explains why. This didn’t just happen to us. It wasn’t the inevitable result of technological change or human frailty. It was done to us.

Her book’s strength is that it is about people, not technology. “This is not a book about social media,” she writes. “There are enough of those. Rather, my focus is on a profound transformation in the dynamics of power and influence, ... a force that is altering our politics, our society, and our very relationship to reality.” The book’s aim, she says, “is to guide you through the evolution of this carnival hall of mirrors, this world of echo chambers, grifters, and keyboard culture warriors, to explain just how we got here and how we might get out.”

Those looking for a big villain—big government, big tech, or big brother—will be disappointed. Instead, DiResta traces loosely coordinated networks of variously motivated manipulators, each reacting to and feeding others to create an emergent ecosystem of lies, half-truths, and conspiracy theories. “Gone are the days of a single, all-encompassing propaganda machine,” she writes. “Now, a symphony of influencers, algorithms, and crowds work tirelessly to construct intricate belief systems, not across society but within their respective niches.”

The internet is not merely a transmission mechanism for content, as it initially seemed; rather, “Recommendation and curation algorithms shape the very nature of content itself.” By monetizing attention, they create powerful incentives to manipulate users with sensationalism and fakery. And—how did we not see this coming?—sociopathic actors took to the manipulation game like fish to water. They swam circles around old-fashioned institutionalists in media and politics.

The author hails from the world of venture capital and tech startups, where she became expert at data analysis. In the mid 2010s, her avocation as an immunization advocate led her deep into online networks of vaccine misinformation. One might have thought anti-vaxxers were technological Luddites, but the opposite was true; they adeptly used techniques like algorithmic manipulation, repetitive messaging, and search optimization to make fringe claims look mainstream and garbage look like science. “Anti-vaccine activists have been at the forefront of leveraging all of the technological features social platforms provide,” she wrote in 2018. The expertise she developed could be applied to other situations, and so the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence tasked her to investigate Russia’s online propaganda methods. In 2019, she became research manager of the Stanford Internet Observatory, which did important work studying how state actors exploit information networks.

Those same techniques could be, and were, applied here at home for profit and political advantage. In DiResta’s telling, the combination of influencers, algorithms, and online crowds exploited and exacerbated social and cognitive vulnerabilities. They created memes and tropes which combined familiarity, novelty, and repetition to be compellingly clickable and shareable. Influencers became expert at gaming algorithmic recommendations, which were tuned to favor engagement and extremism. (When DiResta watched anti-vaccine videos, for example, “YouTube’s recommendation engines began to suggest I might also be interested in chemtrails, flat Earth, and 9/11 conspiracy theories.”) The click business, proving profitable, sucked more investment and talent into the influence game, creating a cycle that spun away from truth. As influencers, algorithms, and audiences trained each other, they altered the realities we see online—and that’s realities plural: “Consensus reality has shattered, and we’re experiencing a Cambrian explosion of subjective, bespoke realities.”

As she traced and exposed the confabulators and influencers, DiResta became their target. They turned all the techniques she had mapped against her. As she relates in the book and in The Atlantic and The New York Times, they made up a story that she was a CIA operative who was at the center of a global scheme to censor the internet. Seizing on the bogus narrative, Republicans in Congress and Trumpy activists launched a ruinously expensive fusillade of subpoenas and lawsuits toward her and other researchers. They also “worked the refs” by insisting that social media companies suppress conservatives (not true; if anything, social media skews right, according to copious research—see here and here and here and here and here); they recoded the terms misinformation and disinformation as slurs aimed by the left against the right; they argued that alerting social media companies and government agencies to false and potentially dangerous material is intrinsically censorious, even if whether to act on those alerts is entirely up to the companies and agencies (and usually, DiResta says, they don’t act).

Now, there are genuine problems with governments’ leaning on private companies to remove or downrank online content. If a U.S. agency has something to tell a social media company, the interaction should be standardized, logged, and subject to oversight. And there are undeniably problems with content regulation by social media companies (government should never do it), because getting it right is wicked hard.

Not regulating content, though, is impossible even in principle. The online world is not an unmediated public square in which people communicate directly with each other; it has no “free speech” setting. Rather, its entire business model is to decide for users what they are and are not likely to encounter—decisions which users can do little to influence and know practically nothing about. “There is no such thing as a ‘neutral’ ranking or recommendation system,” DiResta observes. “Every algorithmic curation system—even the reverse-chronological feed—is encoded with value judgments.”

Even if neutrality were technically feasible, it would not be viable as a business proposition. Social media companies are platforms for user-generated content, yes, and in that capacity they should be open to many kinds of content. But they are also businesses that seek profits, publishers that need advertisers, and communities that set standards and boundaries; and in all of those capacities, they not only can regulate their content, they must. No reputable media company can stand by if its Black customers are targeted with messages urging them to vote on Wednesday. And the fact that identifying misinformation can be contentious does not mean we should stop trying—although election deniers, anti-vaxxers, and Russian and Chinese troll farms hope we will.

I have been in the anti-censorship business since the publication of Kindly Inquisitors in 1993, so I need no lectures about the value of open discourse and heterodox expression. I think it’s great for some social media companies and their customers to prefer relatively permissive content standards. But it’s also perfectly valid for Facebook and YouTube to set higher standards, tell us what they are, and try to enforce them consistently—even if they make mistakes, as they will. And (this should be obvious, but apparently isn’t) it’s also perfectly valid for independent scholars to identify what they think is online misinformation and report it to social media companies, the public, and, yes, government agencies. That’s free speech, too. DiResta grimly notes the irony of being sued and subpoenaed out of existence by people “portraying themselves as champions of free speech even as they try to stifle ours.”

As of now, the anti-anti-disinformation campaign is succeeding. “The government agencies, nonprofits, and state and local officials that had worked to defend American elections in 2020 and 2022 have stepped back in the face of these attacks, concerned about their safety and uncertain about what they were legally allowed to do now,” DiResta writes. “Tech companies have backed away as well.” The Stanford Internet Observatory is in trouble and may effectively shut down.

The irony is that the real Renée DiResta is nothing like Torquemada. She is anti-censorship. She understands that trying to police the internet won’t work and shouldn’t be tried. Instead she favors improving user controls, modifying recommendation engines, diversifying platforms, improving online literacy, and other non-scary measures which you’ll have to read the book to discover.

More important than her specific recommendations, though, is her big-picture takeaway: “For sure, companies and governments must bear their burden of figuring out how to regulate this new space, to restore trust and shore up institutions, but we as citizens have a responsibility to understand these dynamics so we can build healthy norms and fight back. This is the task of a new civics.” Building trustworthy institutions and establishing pro-social norms; that, not censorship, is what works. And don’t we have a word for it? Ah, yes: civilization.

Postscript: Jonathan Rauch and Renée DiResta will both speak at the “Fighting Misinformation without Censorship” panel at the Institute for the Study of Modern Authoritarianism’s upcoming conference, Liberalism for the 21st Century.

Questions they’ll explore include: How will technological advances, especially the widespread use of AI, impact censorship, misinformation, and the way citizens engage with their governments? How does this shift bear on liberal concepts of freedom and society? And what can liberalism offer in managing this shift?

© The UnPopulist 2024

Follow The UnPopulist on: X, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and Bluesky.

I was excited to read the book (I loved books like Active Measures by Thomas Rid), but thought Invisible Rulers perpetuated the moral panic (or elite panic, as Jacob Mchangama calls it) of disinformation/misinformation/conspiracies that Rid was far more nuanced about. (Dan Williams also brings much-needed skepticism to misinformation research.) But instead of engaging with legitimate criticisms, she focused on a few bad actors online and turned the (potentially?) sloppy journalism of Taibbi and Shellenberger into a sinister conspiracy worthy of the nuts she writes about.

And it’s simply not true that she’s anti-censorship. She concludes the book with ideas on solutions and uses the story of how FDR and media companies removed the fascist Father Coughlin off the air as an example. (Her account of this is also incredibly misleading — FDR used broadcasting licenses in order to bully nearly all New Deal critics off the radio, not just fascists; which is ironically what skeptics of the Disinformation researchers are worried would happen. And FDR did it with glee, not “regretfully” as portrayed in the book. David Beito’s book The New Deal’s War on the Bill of Rights and Robert Corn-Revere’s The Mind of the Censor and the Eye of the Beholder are great sources on the history of government jawboning broadcast media.) She also advocates for European-type social media regulation laws, which Jacob Mchangama also critiques well. She also advocates for labeling content with fact checks, which I was hesitantly in favor of until seeing how fast those were politicized and used to protect narratives rather than truth. Should we start putting fact check labels in books? What about music that perpetuates fringe conspiracies (a lot of underground rappers like Immortal Technique have lyrics that would fit right in with Alex Jones and QAnon)?

Even her solutions that don’t involve censorship are ridiculous. She spends the whole book writing about the problems with echo chambers or “bespoke realities” only to come to the conclusion that users should have way more control over what they see on social media — in other word: doubling down on the echo chambers. As she says, “The outstanding question, of course, is what impact self-selection at scale would have on warring factions. Would most people opt in to something extreme that simply reinforces their preexisting bespoke realities? I would like to think the answer is no, but we don’t know enough yet to have an answer.” I completely agree with forcing interoperability and decentralizing social media, but it’s bizarre coming from someone who just spent 300 pages trying to convince people how dangerous it is not to have some nebulous “consensus reality.”

It would have been far more interesting to read about potentially applying possible solutions to polarization (like Amanda Ripley writes about in High Conflict) to the structure of social media. Like, is there a way to get warring factions to play “on the same team” temporarily, which they have rival gang members do in Chicago? Or have users recognize different aspects of their identity rather than the one-dimensional partisan? Or finding a way to “complicate the narrative” in online spaces? Instead, I felt like the book was just a bunch of cheap shots.

It wouldn’t let me hyperlink the articles I wanted to attach, so here are a few of them:

https://unherd.com/newsroom/beware-the-wefs-new-misinformation-panic/

https://open.substack.com/pub/conspicuouscognition?r=4i2vl&utm\_medium=ios

https://open.substack.com/pub/conspicuouscognition/p/yydebunking-disinformation-myths-part-e14?r=4i2vl&utm\_medium=ios

https://open.substack.com/pub/conspicuouscognition/p/should-we-trust-misinformation-experts?r=4i2vl&utm\_medium=ios

https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2022-12-23/europe-digital-services-act-social-media-regulation-free-speech

The whole concept of "mis/disinformation" was so egregiously abused and weaponized during Covid that institutions relinquished their credibility and moral authority to make that sort of determination. It's too bad, because there really are bad actors out there, but unfortunately no small number of those bad actors are embedded at places like the Stanford Internet Observatory.