Is the Lack of ‘Friction’ in Our Virtual World Leading to Liberalism’s Decline?

Our rapid-fire communication technologies may be overwhelming our capacity to deliberate and empathize, two new books suggest

Book Review

Our preferred metaphor for political dysfunction comes from the wrong era. “Gridlock” is a word of fairly recent vintage, first appearing in the 1970s and only becoming a widespread description of traffic in the 1980s. When we speak of “partisan gridlock,” we imagine congressional inaction in terms of a multidirectional traffic jam. But this metaphor carries the assumptions of a bygone era into the present. It presupposes both the desire and the physical possibility of motion—of, once we dig deep enough, friction.

Friction is paradoxical. Because it requires energy to overcome, it slows objects in motion; it brings us to a stop. So we “grease the wheels,” reduce friction on the axle, make cars more aerodynamic. But we also create friction: we replace tires when the tread wears thin; we dump not just solvents but also sand onto icy roads. A world without friction is a world without motion.

But we no longer live in Henry Ford’s America. It’s Mark Zuckerberg’s country now, and friction is no longer a given of the physical universe to be harnessed to our designs. In the virtual reality of the digital era, it’s a nuisance to be overcome. When we are always, already, everywhere all at once, motion comes to feel outdated, just another metaphor-as-relic of the human past.

World Without Friction

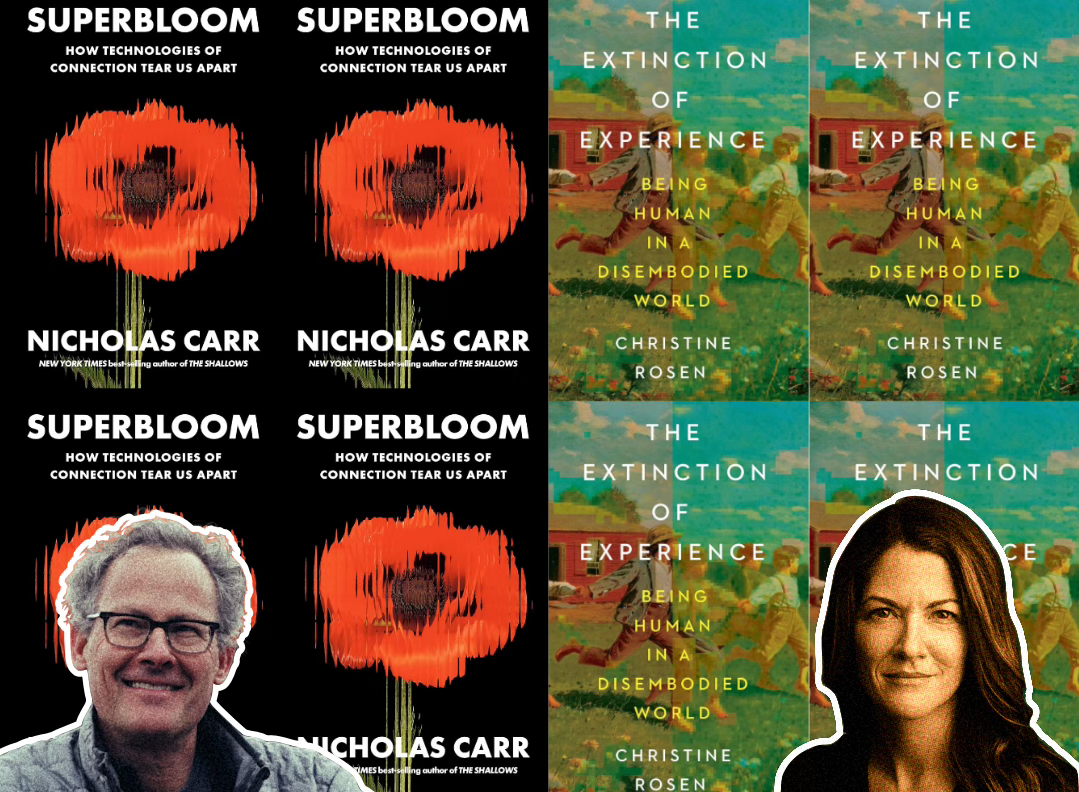

Nicholas Carr and Christine Rosen have written a pair of recent books—Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart and The Extinction of Experience: Being Human in a Disembodied World, respectively—that examine what it means to live in a world without friction. Why, both ask, have the technologies that promised to bring us closer together, to make us happier, to give us what we want, made us more isolated, anxious, angry, and politically divided?

The answer begins in the recognition that, increasingly, we interact as “mediated selves”—as digital, rather than physical, embodied, presences. This has consequences for how we treat others and how we imagine ourselves. Today’s concept of identity—defined more by markers of affiliation than internal qualities—is a form of “self-stereotyping,” Carr notes, “suitable for transmission through high-speed networks” that now pattern our lives. The forms this takes are often innocuous. But the result is different in important ways. Disembodied identity does not easily allow for the development of sympathy and empathy, a point that Rosen backs up with digestible summaries of the relevant research. These move at the slower speeds of the evolved human mind and body. They take time. They require friction.

“Digitization acts as a universal solvent for all that’s tangible in culture,” Carr warns. Perhaps, of liberalism too. In its broadest sense, liberalism is the political structure of living together as free citizens. But what if the human experiences on which that depends are weakening and collapsing? What if its present challenges are less the results of individual actors or movements but of technological advances? Carr and Rosen suggest these questions are necessary to raise as we consider and adapt to our present.

We make sense of new technology through stories, by fitting it into more familiar accounts of the world. The story we told ourselves about the advent of digital media, beginning in the post-Cold War optimism of the 1990s, has largely been one of democratization. This approach informed media accounts and popular sentiment about the early internet, as well as Justice John Paul Stevens’ majority opinion in Reno v. ACLU (1997), which limited its regulation.

The problem is that this story—what Carr dubs “the democratization fallacy”—was doubly wrong: it was neither predictive of what the internet and digital media would bring nor descriptive of the history of social and communications technology that had brought us to that point.

Carr devotes the first half of his book to that history, helpfully summarizing it into four intertwined developments:

Content collapses, as analog media’s regulatory regime and epistemic architecture give way to digitization’s totalizing advance.

Media technology extends beyond its traditional transport function to assume an editorial role, automating judgments about the relevance and quality of information.

People streamline their writing and reading to optimize their efficiency as transceivers of messages on a high-speed communication network.

Social media encourages unchecked self-expression, greatly expanding the platforms’ supply of content but producing feelings of envy, enmity, and claustrophobia among individuals.

Carr notes that content collapse involves the flattening out of previously distinct tools, habits, and experiences into a single platform: think of the number of devices from 2000 that have been incorporated into your phone; or of social media’s roles as postal service, broadcaster, advertiser, and content creator, all wrapped together. This flattening first changed our epistemic architecture (how we learn what is real and what is not)—and then, since 2012, our social architecture (the physical and time-bound rhythms of life that mark events and create separation between public and private). In effect, content collapse rendered obsolete more than two centuries of legal precedent concerning communications technology and media. These depended on the ability to distinguish mass from interpersonal communication, conversations from broadcasts, and, ultimately, physical networks: telephone calls went over wires in our yards; radio and television, electronic broadcasts. And we regulated them differently.

This matters because it helps explain why society and the state have not been able to adapt to (or accept) the ways in which the democratization fallacy was in error.

The internet gives us too much information, too fast. Carr made this argument initially in his 2011 book, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains. But Superbloom further develops the cognitive shortcuts we use to process this information. That we use these shortcuts has been true for a long time—perhaps always. Research in the early 20th century began to confirm that human brains “rely on rules of thumb, intuitive judgments, and other mental shortcuts ... to make sense of things.” And that we imitate: what others believe and repeat, we find increasingly plausible. Descriptions of informational cascades are just as old. In these, “the more people in the group who subscribe to the claim, the more compelling it becomes to everyone else in the group. Even skeptics get carried along. The claim becomes a belief, and the belief a marker of group identity; holding it becomes a social norm.”

Today’s technology—designed to eliminate friction—has removed the brakes on this. Once limited to the slow pace of local conversation, today “cascades can begin anywhere, and they can crisscross a country or the entire globe in a matter of hours, if not minutes.” Social media’s algorithmic incentives mean that “the unending competition to produce messages that will get repeated, that will propagate through the network, is a battle for meaning as well as influence.” “Meaning,” Carr warns, “becomes a network effect. What’s true is what comes out of the machine most often.” Thus, he says, the extremes of both Jan. 6 rioters and cancel culture vigilantism come to be.

This does not mean the internet is broken. Rather, he contends, it’s doing what it was designed to do. Neither are we victims of mysterious overlords from Silicon Valley: “In placing the blame for the internet’s failings on social media companies, we let the net itself off the hook while also absolving ourselves of complicity.” But complicit we are. Our own actions and desires, he insists, are just as, if not more important. All social media has done is “amplify the signal that was always there.”

The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars but in our selves.

Our Mediated Age

Today, Carr and Rosen explain, everything is mediated. Our goals are primarily about communication, not production; images become more important than the objects they depict— “representations of things take precedence over the things themselves.” To illustrate, Carr points to the “superbloom” of his title, the 2019 poppy bloom in Walker Canyon, Calif., which became a social media megaevent, drawing a distinction between a “superbloom” of poppies and the social media event of a #superbloom. The former exists in the physical world: a place to go and see. In the latter, the “media representation turns into a gathering spot,” a place for people to “go” and be seen. “The real thing, the referent, disappears,” he writes, “the carpet of poppies is experienced as an image even before it’s photographed. ... The canyon didn’t exist except as content—content they wanted to be a part of.”

But what is lost in this way of experiencing the world? That’s where Rosen, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a founder of the technology journal The New Atlantis, picks up the thread. The Extinction of Experience attempts to chronicle the variety of human experiences she sees going extinct in a digitally-mediated world. Think of it as Silent Spring, but if we were the subject instead of the environment: a chronicle, but also a call to change course, to develop “a new humanism” that allows us to live in the real, messy, physically-embodied world without rejecting technological progress.

The experiences she focuses on are easy to overlook. Some readers might take them for granted or be inclined to dismiss them as unimportant: handwriting, waiting, being bored, face-to-face communication, the experience of place, space, and serendipity; reverie.

Don’t be too quick to do so. Rosen comes armed with data: lots of it. Take handwriting and especially cursive, that obviously vestigial practice in an era of keyboards and touchscreens. A decade’s worth of studies show that learning to write by hand—and especially to write well by hand—improves literacy, memory, and expression. Typing is more efficient, a fact not without its benefits. But there are trade-offs. Perhaps, she suggests, the decline in reading comprehension among American schoolchildren over the past two decades is not just the result of technology but of the choices we have made about it: that we’ve chosen to prioritize efficiency over friction, even for six year-olds, despite plentiful evidence of the need for friction to help us learn, remember, and be satisfied with our experiences.

Or the face-to-face encounter. Our students, my colleagues and I regularly observe, no longer really speak to one another. They’re constantly communicating, of course—but it’s almost always mediated through their phones even when they sit next to each other. But not all socialization is created equal. Human bodies evolved to communicate in person, looking at each other: this triggers physiological responses that help us process and comprehend the other person. Our language evolved for this too: our words are complemented by modulations in tone and facial expression. Our expressions of emotion are embodied, but we have to learn to read them, beginning young. How, Rosen asks, “do our interactions change when a skill evolution fitted us for—face-to-face communication—gives way to mediated forms of interaction?” In a world where our interactions are primarily mediated encounters, our emotional literacy also declines. We have a harder time reading emotions, assessing trustworthiness, developing empathy, and forming friendships. In other words, having the kind of interactions that liberal citizenship depends upon.

These habits and others under threat of extinction constrain our desire for the efficiency of immediacy over the patient pursuit of long-term goals, both personal and political. The presentism of a mediated life undermines this. “Our new technologies encourage us to value the new and the now, which is why,” claims Rosen, “in the realm of public discourse, we value reaction more than deliberation.”

Liberalism Depends on Friction

So perhaps it should come as no surprise that one of the defining features of our present political landscape has been Congress’ choice to abdicate almost all of its duties and responsibilities. When the world is mediated, when reality is already virtual, “the world’s greatest deliberative body” gives way to the celebrity politician. On the left and the right, the most prominent voices are increasingly those who treat Congress as just another social media platform. Transforming Congress into #congress can efficiently grab attention (and fundraising) but accomplishes very little.

This would also suggest that the forces commonly perceived as threats to liberalism are, perhaps, symptomatic of a less visible but more foundational shift. Liberalism, I increasingly worry, does not just require friction but is the political system of a very specific measure of friction.

This is easiest to see when we turn our attention to Anglo-American conservatism, Burke’s Whiggish counterpoint to a continental tradition rooted in reaction. Conservatism within a liberal political system intends itself to be that system’s friction. It acknowledges (or at least once did) the inevitability of change over time, but seeks to slow it in an effort to adapt wisely, to control the change in order to conserve the structure. Sometimes this tension is achieved prudentially, pragmatically—Eisenhower’s postwar caution that infuriated the extremes of his own party. Sometimes it operates more as a kind of American dialectics, pitting thesis and antithesis against one another—but in a healthy politics, the result has been advance created by that tension, not the stasis of irresistible force against immovable object.

This dynamic plays out left-of-center, too: the dealmaking “moderates” against the more impatient progressives. Clinton and Obama, we might say, knew how to work friction to their own advantage, to adjust to the conditions on the road. But the frictionless society is more visible in its effects on the party of friction—and, through it, more destabilizing: Donald Trump has never promised friction. He’s the frictionless candidate, offering only the immediacy of desire.

The digital mediation of our lives and society will still be with us beyond Jan. 21, 2029. The tools that enable this—smartphones; social media; the internet; and, lately, generative AI—require our attention. They require this attention, in the collective “we,” not just because of the challenges they create for individual health and happiness, but because the societal challenges they pose will be longstanding. Technological revolutions pose challenges to existing orders: this was true of the printing press, the Industrial Revolution, the internal combustion engine, radio and television. To what extent, then, does the current digital revolution present a challenge to liberalism?

I don’t know. And you don’t either. Any answer that’s already at the tip of your tongue is very likely wrong. I also don’t have solutions. Carr and Rosen suggest steps that are modest and, by their own admission, imperfect.

Liberalism, of course, has survived changes in media and technology before; it can again. But this process of adaptation requires knowing which questions to ask and how to ask them: of thinking deeply and slowly; of noticing details. It requires, in other words, the habits friction brings to our lives. In their books, Carr and Rosen have given us the language and framework this task requires.

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

Excellent, excellent review and a must-read for all who care about the future of liberalism and democracy.

Well written