Bernie Sanders Wants to Counter MAGA's Gains With the Working Class by Challenging the Oligarchy

He wants his party to offer a bold social democratic alternative to the neoliberal consensus just as Trump has done on the right

Book Review

Over the past decade, as the centrist neoliberalism that had been the dominant ideological framework in American politics began facing considerable challenges, the major beneficiary proved to be the illiberal right. For a while, Trump’s surprise victory in 2016, especially viewed in light of Joe Biden’s electoral course correction in 2020, was treated by many liberals as a temporary disruption. With Trump’s return to power in 2024, however, they have begrudgingly realized that Trumpism is no accident—not an aberration that can easily be undone, but a lasting force with deeper appeal.

But Trumpism has not been the only ideological alternative to gain ground. All the way on the other side of the political spectrum, the left—in America and abroad—has also seen its popularity grow. Leftist candidates in Mexico, Brazil, and France attained major victories in part by promising to challenge prevailing economic wisdom and, at least in the case of the latter two, block the illiberal right from coming into power. In the United States, self-described democratic socialists like Sen. Bernie Sanders (Vt.) and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (N.Y.) are undoubtedly controversial—but they are also among the county’s more popular politicians, holding anti-Trump and anti-oligarchy rallies drawing tens of thousands. New York City Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani, who also counts himself a democratic socialist, has generated even more interest in this leftist alternative to the status quo.

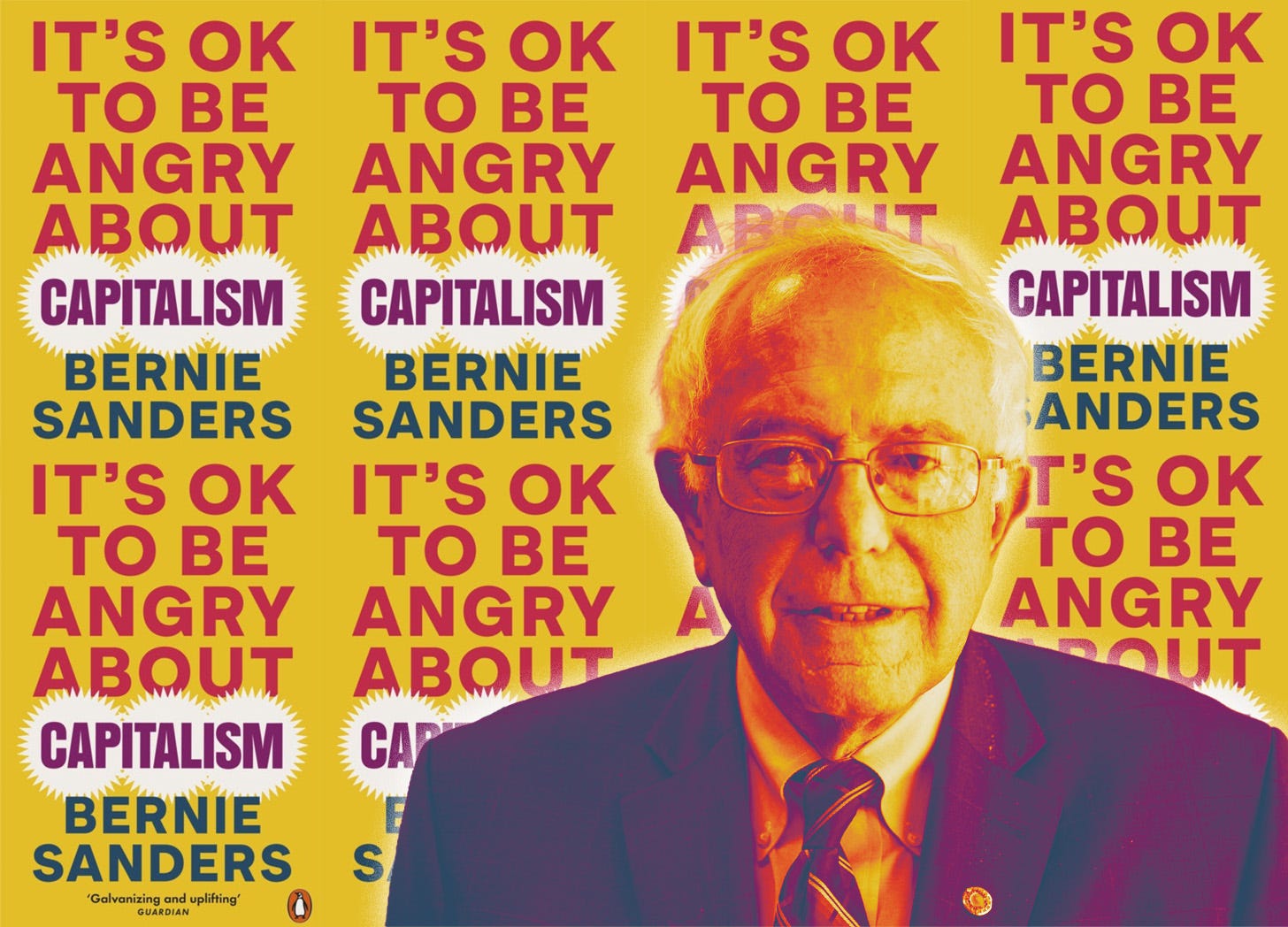

But in thinking about these challenges to the neoliberal consensus of the past few decades, there is no shortage of deep dives into the Trump phenomenon and the global far right more broadly. Less discussed is the leftist alternative. To understand it, at least in the context of American politics, the best place to look is still Sanders, the movement’s longest-tenured standard bearer. His 2023 book, It’s Ok to Be Angry About Capitalism, provides as good a starting point as any of what it looks like in action.

Is There Room For This Shade of Red in the Red, White, and Blue?

For leftists, one frustrating feature of American political commentary is that, while capitalism and liberalism are understood to come in many different forms, socialism is often construed as coming in its worst-possible form: a command economy and authoritarian political system. As implemented in the Soviet Union, Cuba, Venezuela, and other places, this system promised the realization of human equality through temporary political control but ended with brutal dictatorial regimes that exacerbated existing inequalities while creating new ones. While it is essential to repudiate command economics and authoritarianism of any kind, the characterization that socialism is inherently wedded to these features is inaccurate.

The U.S. House recently passed a resolution singling out socialism—and, tellingly, not fascism or its MAGA sibling now raging in America—as intrinsically opposed to American ideals. Its main backer, Sen. Rick Scott (Fla.), literally asked Congress to “condemn socialism as a failed ideology and the antithesis of the American dream,” showing the extent to which “socialism” remains a politically useful bogeyman on the right so that anything with that label is instantly discredited without much further debate or discussion.

Yet recent scholarship has shown that socialism, understood broadly as social equality, has inspired intellectuals from Einstein to Martin Luther King. It is a diverse tradition capacious enough to include many different versions, some more palatable than others within an American political context. Years ago, Sanders walked back, or at least contextualized, praise he gave in the 1980s to some social policies in Cuba, Nicaragua, and the Soviet Union under communism. In 2020, he said: “I have been extremely consistent and critical of all authoritarian regimes all over the world including Cuba, including Nicaragua, including Saudi Arabia, including China, including Russia. I happen to believe in democracy, not authoritarianism.”

In his classic, The Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell defended democratic socialism and opined that it was so common-sensical he was surprised it hadn’t been implemented already. This particular kind of socialism boasts a track record that arguably includes great successes, such as shortening the working day, securing more freedom for workers during the weekend, and championing free trade as a countermeasure to imperialism and authoritarianism. “Nordic socialism,” or what historian Francis Sejersted calls the “Scandinavian variant of socialism” in The Age of Social Democracy, has been the driving force behind some of the world’s most successful societies that have delivered more equality without jettisoning markets.

And it is simply not the case that socialism is an aberration in U.S. politics. Its origins can be traced back to activists like Frances “Fanny” Wright in the 19th century who often coupled concerns of wage labor exploitation with calls for abolitionism and women’s suffrage. As Matt Zwolinski and John Tomasi point out in their pioneering history, The Individualists, many early American socialists saw themselves as libertarians, and were identified as such. In the 20th century, the “Sewer socialists” ran major cities like Milwaukee for decades, a tradition that Sanders himself continued as the Mayor of Burlington, Vermont. Socialist intellectuals like Irving Howe, Michael Harrington, and Helen Keller called out the problems with America’s oligarchic capitalism. Martin Luther King Jr. famously said, “Call it democracy, or call it democratic socialism, but there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country for all God’s children.”

But that was then, and this is now. Sanders’ current charge is to make a case that is realistic and achievable in the Trump-Musk epoch.

Sanders’ Socialist Vision

Sanders’ It’s Ok to Be Angry About Capitalism is an attempt—though not the only recent one—to more clearly establish the parameters of a distinctly 21st-century American socialism. America has always featured enough suffering and injustice for many to be attracted to radically egalitarian messages. But 2025 is a very different landscape from the early 20th century, when Sanders’ hero, Eugene Debs, won almost a million votes on an anti-war, pro-free speech platform.

The first thing to note about It’s Ok is that it largely avoids tackling the first-order questions that usually dominate a socialism versus capitalism discussion. Sanders has little criticism of markets, accepts the importance of the profit motive, and stays largely silent on international economic institutions, a tacit capitulation to the notion that there is no workable alternative to a market economy. Instead, Sanders’ beef is with what he calls the “uber-capitalist economic system that has taken hold in the United States in recent years, propelled by uncontrollable greed and contempt for human decency.”

Frustratingly, the difference between acceptable capitalism and “uber-capitalism” is never clearly demarcated, leaving readers to figure it out from examples. The same problem plagues Sanders’ approach to conveying the essence of democratic socialism: there are worse ways to explain something than by giving examples of it—as Sanders frequently does in his book—but at many points readers could have greatly benefited from a clear definition. Sanders hails from the political arena, rather than the academy, so this is not surprising; even though he is the most well-known exponent of democratic socialism, he’s not first and foremost an intellectual or theoretician.

'Abundance’ Offers a Sounder Way Forward for the Left than Degrowth or Redistributive Progressivism

Still, it’s a missed opportunity, given how little familiarity the American public has with the different varieties of socialism. Plenty of right-wingers know they don’t like it, a lot of young people find it intriguing, and Donald Trump thinks anyone who opposes him embodies it. Sanders gives us a vivid sketch of it in action—just not a clear delineation of what it is conceptually.

Democratic Elites vs the Working Class

Sanders’ book works best as a nuts-and-bolts primer on his political experiences and what should be done to tackle America’s social and economic woes, with one eye on the street and the other on the old boys’ clubs of American power.

The first third covers his political rise and where he thinks the country’s politics have gone wrong. His diagnosis is that while Republicans largely remain the party of tax cuts for the wealthy, they have also shown far more political savvy in mobilizing mass support, including from the traditionally Democratic working class. Sanders argues that this partly stems from the loss of southern Democratic support after the Civil Rights Movement. This explanation misses that much of the working-class drift results from Republicans’ skill in dividing voters against one another through a powerful media echo chamber that blames everyone—women, immigrants, Blacks, Muslims, transgender people, teachers, and union leaders—for the nation’s challenges while ignoring those with actual wealth and power.

Sanders’ mixed, but largely critical, evaluation of the Democratic Party centers on the lack of viable class politics. He argues that by abandoning the working class, Democrats created a “political vacuum” where right-wing populism’s resentments could fester. Democrats have drifted far from FDR’s openness toward condemnations of the “economic royalists.” From the 1990s onwards, Democrats consolidated around “third way” politics pursuing incrementalist improvements. The result is that the Democratic Party, once clearly identified as the party of the working class, has increasingly come to be seen as the party of better-educated and better-off Americans. To adapt Musa al-Gharbi recent formulation, the Democrats have never—or at least not in a very long time—been “woke.” Party elites make symbolic gestures toward equality but have little interest in challenging entrenched power to improve the lives of the least well-off.

To Sanders’ contention that the Democratic Party has left working-class voters behind, left-liberal critics might object that the Biden administration was one of the most worker-friendly in generations, with Biden even joining a picket line. Sanders would likely retort that, while this might have helped him in 2020, those same working-class voters seemed unmoved when they turned back to Trump in 2024. Whatever overtures Biden made, it was all too little, too late. What both Sanders and his critics need to show, however, is evidence that American workers are more animated by economic issues than the culture war battles that are Trump’s bread and butter.

Another objection to Sanders’ claim that the Democrats simply abandoned the working class might come from the Marxist left. The operative presumption is that if presented with an economically left-populist program, the working class would re-realign to its natural home. Some leftists are skeptical. Contemporary Marxist thinkers, like New York University sociology professor Vivek Chibber, have stressed that workers and the marginalized take enormous risks when they attempt to unionize—let alone push for worker ownership of the means of production. Ever since Reagan fired thousands of air traffic controllers, those risks have compounded. This is coupled with an elite-dominated Democratic Party that seems lukewarm toward supporting them and a two-party system that evidence shows overwhelmingly caters to the rich. It’s unsurprising that many people would be suspicious of those who proclaim it can be otherwise, meaning winning back that trust will probably be a long term process no matter what left-of-center program is put forward.

I suspect that, at a certain level, many swing voters who cast a ballot for Trump are aware that he intends to do little for them. But the resentments they feel must go somewhere. Lacking a universalistic politics of inclusion centered around empowering people, the working class and many minorities—ethnic, religious, and sexual, who’ve long been marginalized—turn to a resentment driven politics of dispossession. Barring a viable political movement channeling anger against corrupt oligarchs who use their wealth to buy political power that they then use to consolidate and expand and their economic power, it will be directed at the most vulnerable who are far easier to punish for one’s woes.

Feeling Berned by the Status Quo

Sanders, an independent who caucuses with the Democrats, rejects the ultra-left proposal that the Democratic Party should be abandoned, and suggests the party be reformed to embrace a radical social democratic agenda. This would include: tackling inequality through heavily taxing the wealthy; reinvigorating the labor movement by making it easier to unionize; repealing Citizens United and advancing public funding for smaller local media; guaranteeing voting rights; investing heavily in green technologies while moving away from fossil fuels; breaking up the largest monopolies.

But Sanders’ signature crusade is to achieve “Medicare for All.” For Sanders, healthcare ought to be treated as a human right, and he sees no reason why the world’s wealthiest country should have millions of citizens who lack even minimal health insurance and avoid vital treatments to save money. Sanders and his fellow leftists point out that while countries like Canada are preserving or even expanding care and enjoy longer life expectancies, Republicans have just slashed access to medical care for millions who need it. Though many liberals, including the editors at this publication, have raised serious concerns about “Medicare for All,” Sanders sees it as fundamental to his vision. I am firmly in Sanders’ camp on this one.

An area where, healthcare aside, more agreement exists between liberals and Sanders is the importance of markets. Liberals stress the economic benefits and moral freedoms provided by the free market. Sanders, surely to the surprise of many, does not call for overturning markets and replacing them with state ownership. What he wants is to put “uber capitalism” in its place—something liberals from Adam Smith to John Rawls and self-described socialists like John Stuart Mill would agree is integral to liberal justice. It was Smith in Theory of Moral Sentiments who insisted that reverence for the rich was one of the greater perverters of our moral sentiments and who called for ameliorative programs for the poor and efforts at combating monopolies.

For too long Democrats have focused too exclusively on outreach and messaging over substantive offerings. Of course outreach and messaging are vital parts of 21st-century politics. But the substance of Democrats’ ideology has shifted very little since the Obama and arguably even Clinton years. That has entailed cosmetic or at most minimal efforts to challenge sharpening inequality and provide for the working classes. These efforts aren’t nothing—but they’re not enough. If the current wave of enthusiasm for egalitarian politics demonstrates anything, it is a hunger for a politics of hope and democracy rather than Trump’s fear and oligarchic authoritarianism. Democrats would be wise to pay attention.

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

Good post. However, like Sanders, I think you are underselling the importance of cultural issues for voters. When we say they are being forced / tricked to blame of minority groups by the media, it doesn't take into account key piece of democracy--the negotiations for values around the good life, etc.

Really appreciate how this lays out the diffrence between rejecting markets entirely and challenging oligarchic power. Sanders' core argument about the political vacuum is solid, when you abandon economic solidarity, resentment-based politics fills that space fast. I remeber organizing in rust belt towns where folks wanted concrete policy wins, not just symbolic representation. The trickiest part is that incremental wins do matter, but they're not enough when the structural problem keeps compounding underneath.