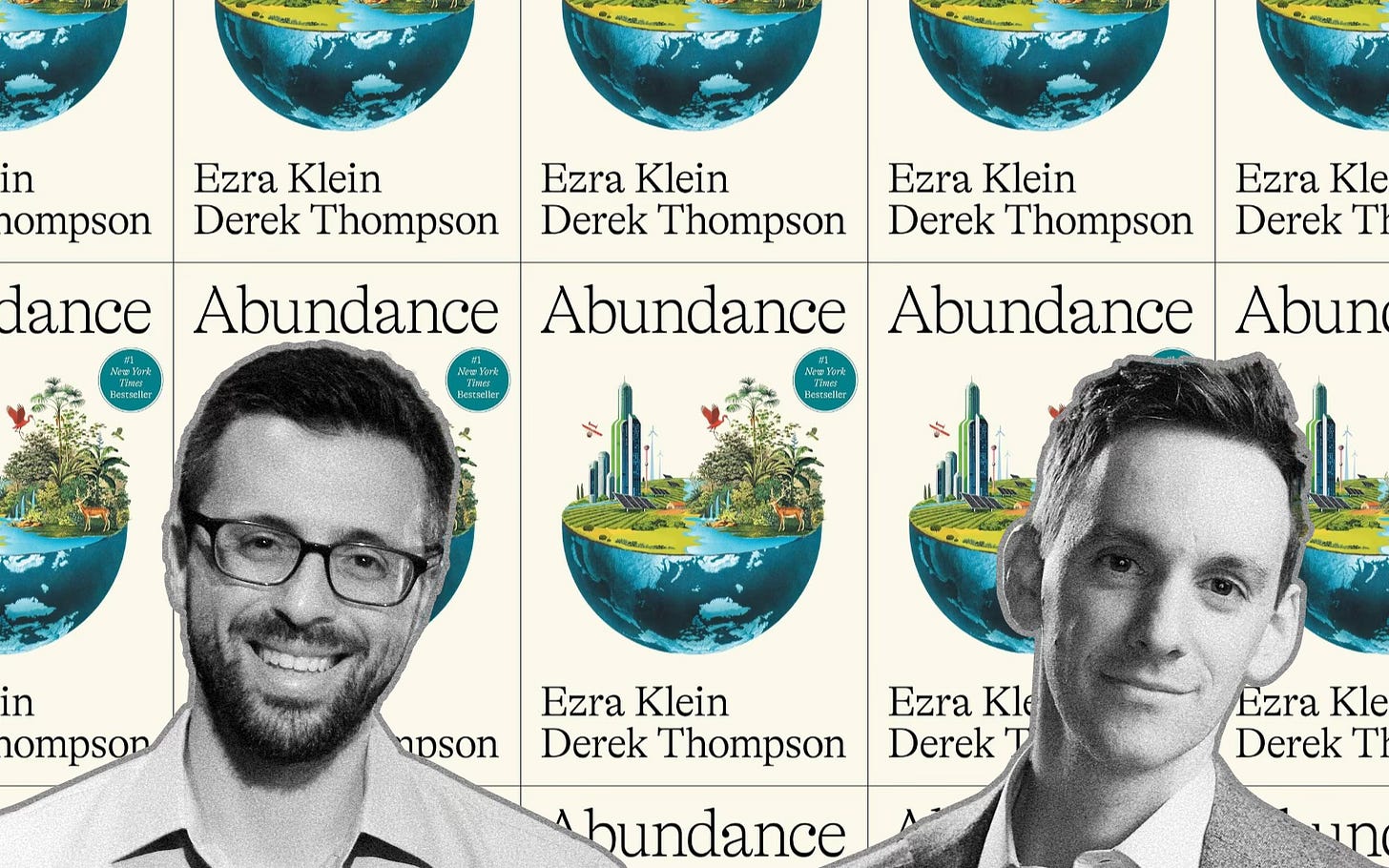

'Abundance’ Offers a Sounder Way Forward for the Left than Degrowth or Redistributive Progressivism

But the authors of this important book might have been more effective had they chosen a less confrontational strategy with their own side

Book Review

The compromises and consensuses that have underpinned American politics for the last several decades have unraveled. But what is to replace them? In the White House, Donald Trump strains to implement a vision of personalist authoritarianism. In the political wilderness—shut out of the executive, both houses of Congress, and subject to the rulings of a conservative majority on the Supreme Court bench—Democratic factions fling recriminations at each other. But we all share the bone-deep sense that something has come unstuck in America—and that, perhaps, the field is open for new programs.

Enter Abundance, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s new book that gathers together ideas developed by the YIMBY—Yes In My Back Yard—movement, as well as others more familiar from science fiction or Silicon Valley techno-optimism. Its underlying idea is simple: “To have the future we want, we need to build and invent more of what we need.”

Rather than focusing narrowly on a single policy issue and proving its point exhaustively, Abundance exhorts readers to dream differently. As the authors note, the goal of the book is not to provide a list of policy prescriptions but to place a new master narrative at the heart of progressive politics—or, as Klein and Thompson suggest, at the heart of American politics generally, in order to form the consensus basis of a major party realignment not seen since 1980. Understanding the strengths of Abundance—and why it is, nevertheless, a bit of a tactical misfire—requires understanding its place in this larger debate.

In Search of Master Narratives

Let’s begin with “process liberalism”—this is the ancien regime, the consensus that has come apart. For decades, in Abundance’s telling, progressivism has been dominated by an obsession with process and regulation. If there is a problem in society, the story goes, it is likely caused by powerful forces of government or capital. So we should restrain the ability of those forces to do harm. This approach, process liberalism, was a reaction to the excesses of New Deal growth machines, emblematized in the twin disasters of urban renewal and environmental catastrophe. “Nader’s Raiders,” activists who followed Ralph Nader’s lead in pursuing progressive policies primarily by suing the government to stop development, embodied this concept. Process liberalism’s failure is most visible in the housing crisis wracking blue states.

What are the rival master narratives, for progressives, to the ancien regime of process liberalism?

The first is Occupy Wall Street, which burst onto the political scene in 2011 with the electrifying slogan, “We are the 99%.” That slogan would be taken up by Bernie Sanders in his 2016 presidential primary run and by the explosively growing Democratic Socialists of America. Neither Sanders nor the DSA was able to stage a formal takeover of the Democratic Party, but the master narrative they offered clearly moved a great number of people, including many left-wing intellectuals, and continues to do so today. We can boil that narrative down to a simple premise: the 99% are struggling because wealth and power are being hoarded by the 1%, the billionaires and their corporations. We can fix America’s problems, the recommendation goes, by attacking corporations, breaking up concentrated power, and redistributing their wealth. This narrative seems to underlie much of progressive policy, whether or not it bears Bernie Sanders’ name. Tax and redistribute—what could be more progressive than that?

The other rival master narrative, as Klein and Thompson note, is the philosophy of degrowth that has become popular in certain elite intellectual circles. It begins not with billionaire power but with climate crisis: the world has a fixed carrying capacity, and we are exceeding it. If we are to survive as a species, we must all consume less. The dark mirror of degrowth is the right-wing populism embodied by Trump. Yes, Trump says, the pie is fixed—so if we’re going to have more, others will have to have less. Grab, grab, grab. Upset about the price of housing? Blame an immigrant. Upset about losing your job? Blame China. Upset about your son not getting into college? Blame the woke. There’s only so much housing, so many jobs, and so many college slots to go around—so we better find some subalterns to take them away from.

Klein and Thompson’s grand move is to diagnose all of these master narratives as ideologies of scarcity. However much they differ in the details, these ideologies share a single foundational truth: there's only so much to go around. Abundance asks us to imagine a world where we can solve our problems by building more: more housing, more green energy, more universities, more medicines, more science, more everything.

The Progressives Strike Back

Abundance, perhaps unsurprisingly, has attracted a slew of left-of-center critiques. Some have been measured; others have analytically relied on targeting the authors’ class position (“the abundance vision ... [an] upper-middle class experience that might well reflect the authors’ lives ... reads like a rich suburb gone green.”) or on subsuming Abundance within Silicon Valley reactionary futurism (“Abundance is a de facto book-length companion piece to [Marc] Andreessen’s pandemic-era essay ‘It’s Time to Build.’”), despite Klein explicitly disavowing key planks of that perspective in print. One consistently leveled charge is that the book is neoliberal: it celebrates the market and denigrates government—or, as a swarm of angry people will yell at you if you mention Abundance on Bluesky, “Abundance is just rebranded Reaganism.” Despite Klein and Thompson’s repeated defenses of government, there is a certain crowd that is convinced that Abundance is just a stalking horse for a familiar Republican program of deregulation and tax cuts.

In his publishing-circuit interviews and podcasts, Klein appeared surprised by this strain of criticism. On one level he is right to be: the book explicitly endorses strong government intervention in the economy as essential to abundance. There is no discussion of tax cuts. It endorses environmental protection as a goal.

And yet Abundance repeatedly picks fights with progressives. Within the first 30 pages it praises AI, Tesla, and return-to-office. When it discusses the necessity of supercharging science and innovation, it moves quickly past guaranteed progressive crowd-pleasers like “increase immigration” and “increase funding for universities” and on to “metascience,” the speculative process of using scientific methods to improve our strategies of science funding—a topic primarily of concern to Silicon Valley intellectuals. Other sections speculate on the necessity of both powering and controlling a soon-to-come artificial superintelligence. And, of course, Thompson did Abundance no favors by promoting it on the podcast of Richard Hanania, who despite recent and occasional anti-MAGA leanings remains a notorious scientific racist. In sum, Abundance does very little to offer progressive intellectuals a spoonful of sugar—indeed, it embraces shibboleths and cultural signifiers almost guaranteed to put progressives off their supposed medicine.

Going Around the Gatekeepers

A suspicion of the authors on a personal level appears to be at the core of much of the criticism. But then, if you announce that you are coming to slaughter the sacred cows, you should not be surprised when the cows object. But this is the big political bet of Abundance: that Klein and Thompson can go around the progressive intellectual gatekeepers and speak directly to the progressive base, to ordinary people. This is not a matter of speculation; they discuss the place of Abundance in a hoped-for political realignment in some detail in the concluding chapter. They quote Gary Gerstle on what forging a new master narrative will require:

a capacity to shape political opinion both at the highest levels ... and across popular print and broadcast media; and a moral perspective able to inspire voters with visions of the good life. Political orders, in other words, are complex projects that require advances across a broad front.

There is a reason this book is being sold in Barnes and Noble and Hudson Books. There is a reason it’s the kind of book you could buy your dad for Christmas. Klein and Thompson are willing to pick these kinds of fights with progressive intellectuals because they gamble that they can, in so doing, speak more directly to the progressive base. In some ways, that has been my experience: for every highly-engaged progressive screaming at me that Ezra Klein is a fascist, there is a normie Democrat replying, “I read Abundance and thought it was good.”

This represents something of a departure from other books in a similar vein. Consider the larger context of the YIMBY movement and intellectual tradition: books like Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page Aldern’s Homelessness is a Housing Problem, Paul Sabin’s Public Citizens, or even that classic of the canon, Donald Shoup’s The High Cost of Free Parking. These books are narrow, focused, and detail-oriented. Colburn and Aldern’s book, for example, wades through extensive academic literature and quantitative studies to carefully examine—and rule out—every alternative explanation for regional homelessness rates other than: “it’s the price of housing, stupid.”

From a political perspective, those books are engaged in trench warfare: the slow, grinding process of shaking progressive intellectuals out of their dogmatic slumber by narrow but unassailable argument. Abundance is not that book. It represents a new move: the attempt to take these ideas “on the road” and bring them to ordinary voters in a bold narrative of a better future.

Abundance Progressivism?

But in all this I have not answered a simple question: Is Abundance right? In the broad strokes: absolutely.

The housing crisis is indeed caused by a crippling scarcity of housing. Blue states do spend tens of billions of dollars on infrastructure and get astonishingly little in return. The climate crisis cannot be solved without building enormous amounts of green energy, transmission lines, and—yes—carbon capture facilities. If we cannot build more housing, if we cannot build infrastructure, if we cannot build green energy, then we have nothing to offer the American people—nothing other than a feel-good progressivism that appeals to virtue-signaling homeowners comfortable with the way the world is and unwilling to do much to change it. And in all of these cases, it is inarguable that our current system of regulation is behind much of our inability to build.

What I disagree with is Klein and Thompson’s confrontational strategy. But progressives are right: Corporate power is also a problem! Wealth inequality is also a problem!

The issue with contemporary progressivism, though, is that so often “disciplining capital” is filtered through the lens of process liberalism. Consider the program of “value capture” in urban development. The idea is that governments will require developers of new market-rate housing to also perform various other civic tasks (beautification, affordable housing), thereby capturing some of the value capital creates and transferring it to the public. In practice, what policies like inclusionary zoning actually do is create a tax on new construction. You end up getting less housing, fewer public benefits, and the (hidden) transfer of money from the public to existing homeowners who benefit from the scarcity of housing, widening the gulf of inequality.

Consider likewise the problem of environmental protection. A common criticism of Abundance is that it advocates for more environmental destruction in the name of growth. As Klein and Thompson repeatedly emphasize, they believe in protecting the environment. But Abundance’s critics have failed to recognize the distinction between environmental laws like the Clean Water Act and those like the National Environmental Policy Act. The former sets clear standards in pursuit of specific environmental goals and leaves industry alone to figure out how to meet them; the latter does not mandate any environmental goals or environmental protections—rather, it requires government agencies to produce reports stating what they expect the environmental impact of their decisions will be. And these reports can then be challenged by private citizens in court for being insufficiently comprehensive. In practice, it’s a mechanism for endless legal headaches for anything new—even congestion pricing or green energy!

This is the power of a master narrative to shape intellectual terrain. If your narrative is about disciplining capital, then anything that looks like capital discipline seems good—even if it strangles the green energy we desperately need. On the other hand, the abundance narrative is not immune to such seductions. If your narrative is “regulations are hampering growth,” then anything that looks like a regulation might be a candidate for attack—even if there’s no evidence that it’s the source of our problems. It does not take much imagination to understand how this can serve right-wing ends.

Master narratives are seductive. But for precisely that reason they are dangerous: by making politics a matter of identity, they obscure areas of agreement. Ned Resnikoff has argued that the YIMBY agenda—and its abundance extensions—has a lot to offer those who wish to discipline capital. Rentiers, monopolists, and oligarchs thrive when malfunctioning regulations create barriers to competition. But abundance-aligned reforms can help us increase democratic control over the economy and sustain a thriving housing market. We can build green energy and tax billionaires and protect trans rights, all at the same time. These don’t have to be competing policy goals.

W. David Marx argues in Status and Culture that to succeed as a cultural innovator, you must simultaneously satisfy two inherently contradictory goals: prove that you are a genuine member of a group, while simultaneously standing out from that group. But Klein and Thompson have messed up the former task: reassuring progressives that they can embrace abundance without forfeiting their progressivism. They can, though. We just have to show them how. Ultimately, abundance liberalism must be willing to be a bit protean, flexible enough to accommodate itself to a variety of political identities, while maintaining consistency on its core policy: abandon artificial scarcity and build.

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

Years ago when I worked at what was then the world’s largest financial services company, our chairman would enjoin us to own “a share of mind” of our customers. It was not as clunky as it sounds. How often and how quickly will our clients turn to us when they have a particular need to be met?

Democrats, in their present parlous state, are looking to increase their share of mind among the electorate. All this supply-side progressivism talk is to make voters associate the Democrats with being the party that most efficiently provides the enabling conditions (now called state capacity) for Americans to pursue the American Dream that neoliberalism has promised them. In that sense, abundance progressivism is the handmaiden of neoliberalism.

But can we do anything about it? Sadly, no. Looking back at the great sweep of American history since it began its industrialization, it’s seems clear to me, albeit belatedly, that a feral kind of capitalism is embedded in the identity of this nation. The state exists to rescue a business and financial sector fuelled by animal spirits when it runs amuck. Only when there is a catastrophic economic crisis that discredits that economic model is there a shift in the relationship between state and society more broadly.

And one could argue that the Great Depression too in the end rolled out a safety net for businesses. In return it asked for a semblance of a welfare state. That side of the bargain had been progressively (sic) shredded since the 1980s. The hubris of the private sector is now so great that it wants to perform its high wire act with no safety net.

An insightful post. Abundance pairs very well with progressivism and progressive goals, so I'm disheartened by a lot of the infighting, which seems largely unnecessary. I will say a fair number of critics of Abundance clearly didn't read the book. David Austin Walsh admitted he only "read bits and pieces", though I'd wager he didn't read it at all.

My area of interest is medical research targeting aging biology to treat/prevent age-related diseases and increase healthy lifespan. While there has been talk of abundance related to healthcare, especially from the Niskanen Center, medically targeting the biology of aging to fundamentally change 21st-century medicine is still largely unknown, despite fast-growing support; examples includes ARPA-H programs PROSPR to develop aging biomarkers and run FDA clinical trials against them and FRONT to realize functional repair of neocortical tissue. PROSPR is run by a researcher who was a mentor in Longevity Biotech Fellowship, and FRONT is managed by the author of "Replacing Aging."