Free Trade Has Stronger Intellectual Roots in the Left than the Right

Before the Cold War, free market liberals and Marxists both saw commerce as a force for global peace and equitable prosperity, a historian shows

Book Review

For a long time, the conventional wisdom has been that the world is becoming increasingly economically integrated, that this process is a historical inevitability, and that only a fool would spurn its benefits. Over the past few months, Donald Trump has attempted to refute the first two theses through a personal embodiment of the third. His declaration of economic war against virtually the entire world led much of it to respond as anyone would expect.

When Trump first announced his candidacy a decade ago, many were surprised at the spectacle of a Republican politician so enamored of tariffs. This profoundly challenged the orthodoxy that being an American conservative meant being a vigorous proponent of free trade. That surprise has persisted. Recently, even the Chinese seemed bemused, invoking Ronald Reagan’s speeches to mock the American right’s shift.

But this surprise reflects another aspect of the aforementioned conventional wisdom—that the left tends to be wary of trade, globalization, and markets, whereas conservatives are the heralds of capitalism. After all, wasn’t it the two most iconic conservative leaders of the late 20th century—Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher—who won the Cold War for markets, global trade, and the KFC Double Down?

When Free Trade Was Left-Coded

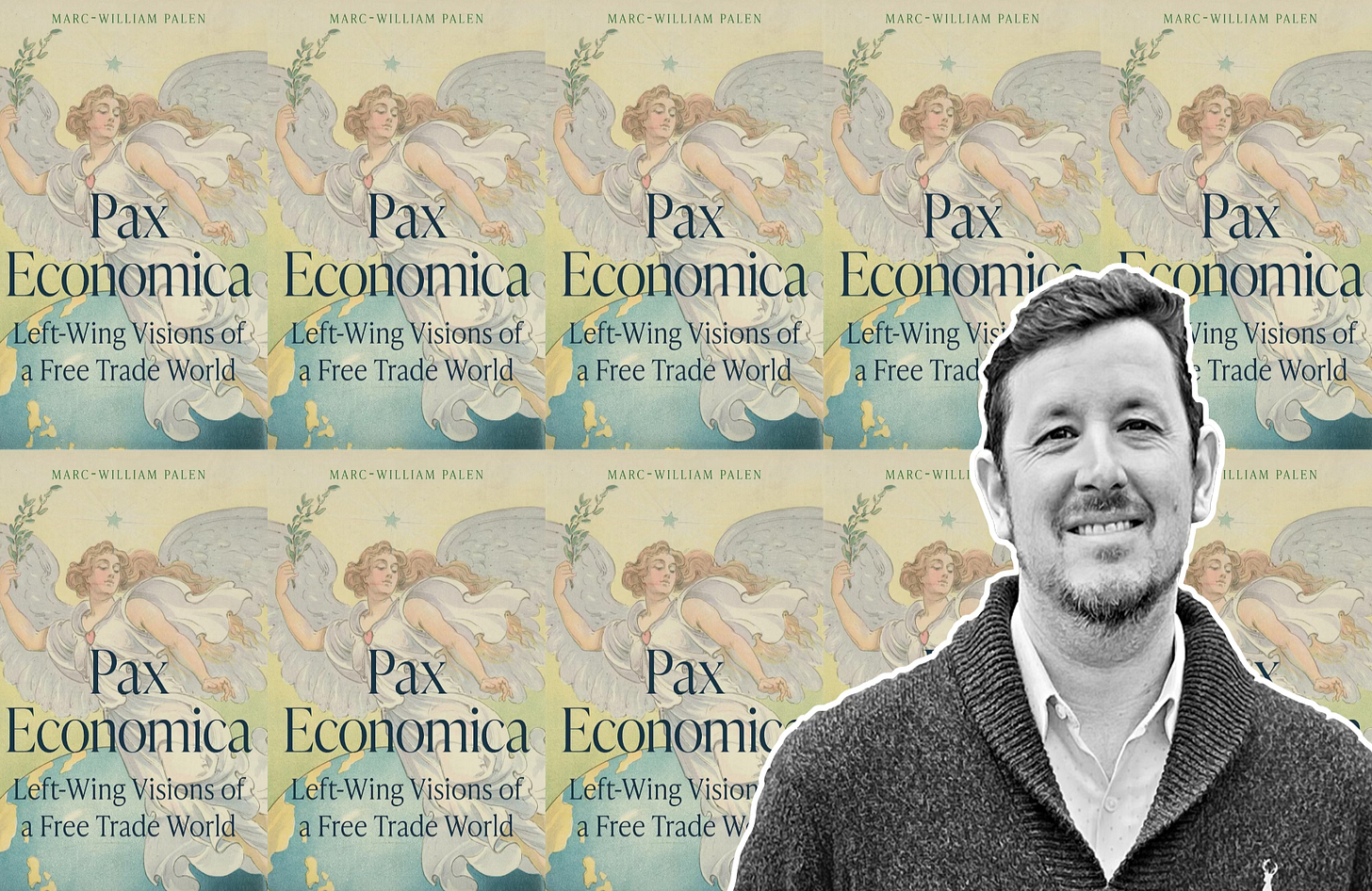

Marc-William Palen, a history professor at the University of Exeter and co-director of a History and Policy Forum focusing on global economics, seeks to upset that narrative. In his new book, Pax Economica: Left Wing Visions of a Free-Trade World, Palen challenges “Cold War lenses” with invigorating freshness. He introduces a “spectrum of left-wingers” who variably:

…sought reform, others revolution, but all shared the belief that economic independence would foster democratization, economic and social justice, and world harmony. For some left-wingers like Karl Marx writing in the 1840s, the envisaged interconnectivity wrought from free trade signalled the next progressive step in capitalism’s march towards proletarian revolution, and therefore deserved support. But for many other left-wing internationalists, universal free trade came to be seen as the economic bedrock of a more peaceful, prosperous, and democratic world order. ... These same social democrats, democratic socialists, and communists nevertheless often found themselves working alongside their more moderate liberal radical contemporaries to realise their shared vision of a peaceful free trade world.

Liberal radicals, democratic socialists, Marxists, and left-libertarians ... not exactly a collection of intellectual traditions one would expect to share a respect for the same economic solution. But as Palen makes clear, they each came to endorse free trade as an antidote to imperialism, deprivation, authoritarianism, and war. The global interconnectivity that they sought would create ties of such mutual dependence that, gradually, nationalist xenophobia would soften; conflict would become so toxic and costly, they thought, that none would dare indulge it. The alternative, economic insularity, would lead to declining standards of living—especially for the poor—and sharpening nationalist tensions between great powers and those aspiring to join the club.

Palen devotes a lot of space to exploring those overlapping affinities between groups who in other respects diverged widely. He notes how both Marx and Engels endorsed free trade as a means of integrating the global economy and thus bringing the working classes of the world into contact with each other in preparation for their expected revolution. Later Marxists took a less instrumental view of free trade. Luminaries of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) such as Eduard Bernstein and Karl Kautsky worked to combine “Manchester liberalism and Marxism.” Kautsky’s support for “free trade remained remarkably consistent,” Palen writes, “and was tied closely to his antipathy towards German protectionism and colonialism.” Bernstein, likewise, was influenced by both Engels and the British free-trade tradition, believing it to be beneficial for “the proletariat and the bourgeoise,” and identified nationalism and protectionism as partly to blame for German militarism.

Alongside these socialists were radical liberals and feminists who shared many of the same aspirations: Richard Cobden, the British politician and author who tirelessly campaigned for free trade and peace; fierce pro-marketeers like Frédéric Bastiat, who lamented that industrial lobbyists had led to the formation of “Fortress France” against the world; and a young Joseph Schumpeter, who “portrayed imperialism as a monopolistic symptom of atavistic militarism and protectionism—an ailment only democratic free-trade forces could cure.” Georgists like Frederic C. Howe and Leo Tolstoy felt that a tax on land, combined with free trade, would bring about a new epoch of peace. The author of War and Peace even saw “free-trade through land reform prescription” as the “economic means to implement his spiritual philosophy and for dismantling Russian serfdom.” Feminists in the Young Women Choosing Action (YWCA) movement crusaded for free trade as an antidote to the wars they saw claiming generation after generation. Women’s groups aligned the cause of peace and economic prosperity with what Palen describes as an ethic of maternal care.

This vision of a pax economica might have seemed just that—a mere vision, not reality. But Palen argues that it came close to being realized in the postwar period. Major international institutions committed to peace were founded, the colonial powers began (begrudgingly) withdrawing from their fiefs, and integrative efforts in Europe and beyond gained traction. Lamentably, despite these favorable conditions, the pax economica did not materialize; indeed, throughout the book, there is a sense of a noble path not taken, though Palen makes clear that it’s not too late to try again.

What Happened to the Pax Economica?

Palen contrasts free traders on the left with a counter-canon of (usually) conservative economic nationalists. In the United States, this took the form of arguing for a “strong fiscal-military state with subsidies for internal improvements and infant industrial protectionism: what became known as the ‘American system’ in the decades preceding the country’s civil war.” In Germany, a confluence of “protectionism, conservative nationalism, and colonialism, first under Bismark and then under Wilhelm II” was a key point in the conservative reconstitution of a German empire. Today, Trump’s America First economics has “included trade wars with the nation’s main trading partners, pulling the USA out of the TPP, scrapping NAFTA, and working to dismantle the WTO from within.”

A recurring worry, which runs from Bismark through to Trump, is that the interdependence engendered by free trade is a form of weakness. Many endorsed a combination of autarky and imperial expansion in response: if their nation could acquire enough land, resources, and subjects, then it could avoid dependence on foreign trade. It could dictate control of its economic life, and those of its human subjects and puppet states, from above. At their most virulent, Palen notes, these ideas culminated in Hitler’s “economic nationalist Nazi empire,” which adopted:

German colonial methods from south-west Africa as it looked to Latin America and eastern Europe for colonial exploitation. These ‘indolent’ regions were to have become peripheral agricultural producers to feed the German industrial centre. ... In the case of Nazi-occupied Poland, this is effectively what transpired.

Palen’s narrative—left-wing free traders of all stripes set against largely conservative economic nationalists—is an appealing one today. But is Palen anachronistically reading history to build up and explain contemporary events? And what does it mean for his thesis that figures like Thatcher and Reagan were among the most prominent recent advocates of free trade? And what about all the various forms of statist autarky adopted by socialist regimes throughout the Cold War?

Much of Pax Economica is devoted to exploring these issues. On Palen’s telling, the overlap between radical liberal and socialist commitments to free trade began to break down after the Russian Revolution, when Stalin endorsed the idea of socialism in a single state. But the real split, Palen contends, came from the widespread perception, among former colonial subjects, that “free trade” as understood by the Western powers meant neo-imperialism in practice. They had a point—free trade was sometimes imposed in blatantly hypocritical ways, such as demanding open trade for Western goods but imposing tariffs to protect economically vulnerable industries.

At times it could become even more sinister: Palen points out that, after the Cuban Revolution in America’s backyard, the U.S. set up a longstanding and crippling economic embargo of the island nation. This was done in the name of human rights concerns—concerns which didn’t stop the U.S. from trading with far more brutal regimes, many of which it had a hand in creating. The U.S. and its allies frequently intervened to overthrow democratically-elected but left-wing governments across the world, ranging from Iran to Chile to Haiti, often seizing resources and industries for American capital. All this led statesmen like India’s Jawaharlal Nehru to conclude that non-alignment in Western-led economic systems was simply the safer course to maintain a fragile, newly enjoyed independence.

Once More on Neoliberalism

Probably the most controversial element of the book is Palen’s sharp condemnation of neoliberalism, defined by intellectual historian Quinn Slobodian as a global project to encase and protect the market from political, even democratic, pressures.

Palen claims neoliberals gained ascendency between the 1970s and 1980s and “ostracized free trade’s left-wing supporters from the very supranational institutions and structures they had helped create.” He acknowledges ideological affinities within the Manchester-Marx nexus, with “right-wing intellectuals like Friedrich Hayek” drawing from the same “liberal wellspring as the commercial peace movement, and saw many of the same globalist postcolonial opportunities stemming from decolonization.” They also “supported supranational oversight and diminution of national sovereignty to enforce it,” Palen notes. But in contrast to thinkers and activists emerging from the Marx-Manchester nexus, the neoliberals were “deeply critical of the welfare state, anti-colonial nationalism, and trade unions.”

The neoliberals were also far more willing to disconnect their commitment to capitalist freedom from other, crucial kinds of liberal freedom. They were willing to support authoritarian regimes from Pinochet’s Chile to South Africa, so long as they got on board with the right economic program. Thatcher and Reagan, widely seen as avatars of neoliberalism, saw little conflict between supporting the purported freedom that came from capitalism and propping up authoritarian regimes abroad. Thatcher exercised a heavy hand at home in crushing the labor movement, and wasn’t above using torture to crack down on militarism in Northern Ireland. By the end of the Reagan-Bush years, there were more people in jail in the U.S. than the Soviet Union. In each case, full freedom for markets didn’t require full liberal freedoms for the lower orders.

For Palen, neoliberals largely saw in free trade a means of spreading capitalism and rewarding capitalists. They reaped profit while being indifferent to, and even distrustful of, “democracy, human rights, and national sovereignty.” At their worst, for neoliberals, “democracy was no longer seen as an accompaniment to worldwide free trade, but as an impediment.”

Palen’s Pax Economica therefore joins a growing literature that advances a more complex analysis of the idea that Trump’s economic nationalism represents a radical break from neoliberalism. Modern economic nationalism does indeed dispense with free trade and internationalism—but in Palen’s telling, cooperative and egalitarian internationalism was never a paradigmatic feature of neoliberalism in the first place. Instead, the vision of a free and open world of trade is more closely aligned with the Marx-Manchester lineage of thinkers. On Palen’s view, the dim evaluation neoliberals took of human rights, democracy, and developing countries, their espousal of a competitive and non-solidaristic ethic, and a fascination with hierarchical power all did little to bar right-wing populism and arguably helped catalyze it.

This is an interesting theory, but one not given enough space or argumentation in a history that very much feels like it was written with the present and future in mind as much as the past. Figures like Friedman and Hayek may have been wary of elements of the welfare state. But Friedman was also willing to flirt with arguments for Universal Basic Income, and Hayek consistently indicated that he wasn’t opposed to various forms of insurance against unemployment (and perhaps even for public healthcare). Moreover, far from being distrustful, neoliberals often invoked the language of human rights and democracy to justify interventions in Cuba, Iraq, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere. Even if much of this was done to smooth the way for their other views, or ideological whitewashing for imperialism, it does complicate Palen’s claims. If liberal socialists (like adamant free-trader John Stuart Mill) could justify imperialism as a humanitarian, civilizing mission, there is no reason contemporaries might not be similarly led astray despite good intentions. Hopefully Palen graces us with a sequel that further develops these complex arguments.

While reading Pax Economica, I was reminded of Matt Zwolinski and John Tomasi’s The Individualists, which I also found to be excellent. That book tells a somewhat melancholic story of a libertarian movement that was proudly radical, often egalitarian, and even willing to embrace socialist solutions as a response to the rich fleecing the poor. In Zwolinski and Tomasi’s telling, these alignments were shattered by the Cold War, where history was blurred and liberalism and libertarianism both took sharply conservative turns. These turned out to be disastrous ... for liberals and libertarians, who lost their identity by either drifting into the MAGA haze or finding themselves untethered from their prior philosophical moorings.

Pax Economica tells a parallel and vital story about radical liberals, left-libertarians, socialists, Marxists, and feminists who united in a shared commitment to free trade, anti-imperialism, cosmopolitanism, and peace. For a brief moment at the end of the Second World War, they managed to push much of the globe in a freer direction. But the Cold War broke apart these ties, leading many liberals to see the left as their arch-enemies and vice versa. Palen ends with a call to rediscover the economic peace movement’s “radical history” as “left-wing internationalists search for a new foreign policy to combat both neoliberalism and a new twenty-first century protectionist order.” I hope we find it.

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

I will need to read this one and write reviews in Swedish and Serbo-Croatian. I recognise that just as there is a Left and a Right, there are left-wing individualists and collectivists, as well as right-wing individualists and collectivists.

My progressive father once told me that he was already in favor of globalisation during the 1970s in Yugoslavia when he was able to be transported in Japanese cars, listen to music from America, and watch softcore movies from Sweden in his town.