Why Courts Can't Save America From This President

Our system has depended on norms, not laws, against the abuse of executive power and those are outside the scope of the judicial branch

Last week, Aug. 14 to 15, the Institute for the Study of Modern Authoritarianism, The UnPopulist’s publisher, hosted its second annual, ”Liberalism for the 21st Century“ conference at the Watergate Hotel in Washington, D.C. The sold-out event, which brought together many shades of liberal intellectuals, journalists, advocates, dissidents, and activists from all over the world, was a huge success. Its goal is to build a platform where anti-authoritarian freedom fighters can come together to exchange ideas and share strategies for defeating tyranny. It’s also a forum for thrashing out a revitalized liberalism that can address the problems of this century. And if the enthusiastic response to the event is any indication, we are building steady momentum.

We will publish a post of some of the responses we received later this week. But we want the important discussions at the conference to reach a broader audience, so we will be sharing the videos and transcripts of many of the panels. We have already published ISMA President and The UnPopulist Editor-in-Chief Shikha Dalmia’s opening address and Russian dissident Vladimir Kara-Murza’s dinner keynote.

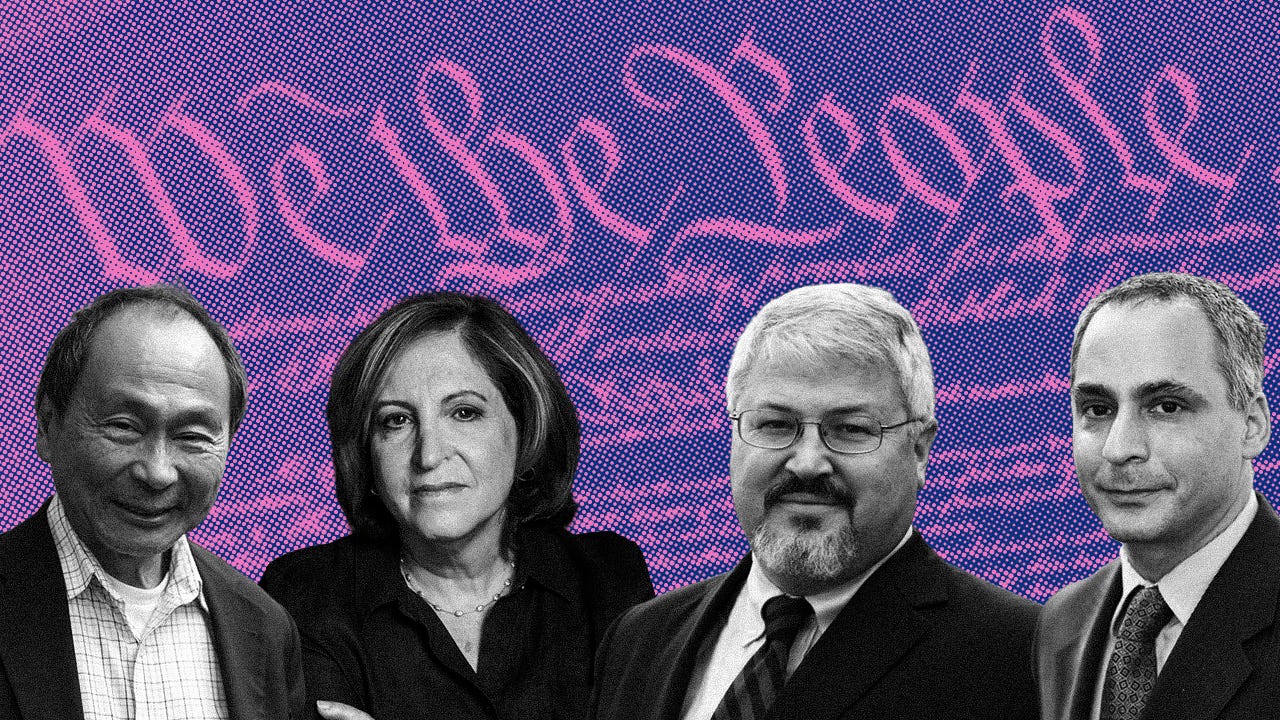

Today, we bring to you, “Liberalism at a Time of Constitutional Crisis: Taking Stock of U.S. Democracy,” our all-star opening panel featuring Stanford’s Francis Fukuyama, former Washington Post editor Ruth Marcus, and Harvard’s Jack Goldsmith. It was masterfully moderated by Lawfare editor and constitutional scholar Benjamin Wittes. This was a really important discussion that offered a sober—and sobering—assessment of the Trump administration’s institutional assaults and how its targets have held up. The participants disagreed about the role that courts can realistically play in pushing back against Trump’s authoritarian machinations—but they all agreed that we are in a great deal of trouble.

What follows is the full video and transcript, audience questions included, lightly edited for flow and clarity. We are certain you will find it immensely useful.

And if you are looking for accompanying material, we highly recommend re-reading Andy Craig’s brilliant commentary, “There Is No Piecing Back Our Badly Shattered Constitutional Order,” that powerfully argues that Trump’s actions have rendered our system unworkable, and until we embark on an active program of constitutional reconstruction, our disputes will be resolved not by laws but state might.

Benjamin Wittes: Frank, you said you wanted to address the assault on the deep state. That’s a great place to start. When we heard about mass layoffs before, I assume we have some people in the room who were affected by that; it’s hard to have a room this big in Washington without that right now. How severe do you think it all is? And what do you think is the relationship between that assault, if we will call it that, and liberalism?

Francis Fukuyama: So, I actually like the deep state. I think that any functioning political system has to have a civil service that meets these basic Weberian requirements of being nonpartisan, expert, professional. That has really been the target of this current administration; a lot of Project 2025 was really about what they would do to the so-called deep state. One of the deepest political characteristics of American culture is distrust of government—so this is nothing new. But the ferocity of this particular attack is quite unprecedented. It’s already done a lot of damage. But, unfortunately, I don’t think it’s over because they still have an agenda that they haven’t fully carried out. So let me just describe the different parts of it.

The beginning part was DOGE, the Department of Government Efficiency. It built on something that was actually a very good part of the U.S. government, the U.S. Digital Service that Jennifer Pahlka and others in the Obama administration had established to try to modernize the digital systems of the U.S. government. DOGE began with the assumption that the U.S. government doesn’t actually do anything all that important, that most of the workers are sitting at home playing video games, and therefore if you fire a random 10 or 20% of them, really nothing is going to happen. It was carried out by people outside the government, by twenty-something engineers that had no concept of what it was that these different government officials did. So they did these random firings.

I think people are aware of this, but there are several aspects that we haven’t fully understood the effects of. The computer systems that the federal government uses are extremely fragile and very old. A lot of them are written in Fortran or COBOL or languages that modern software engineers simply don’t know anything about. They’ve been patched together by heroic civil servants over decades. It’s very hard to know exactly how they could have broken these systems. But the more sinister thing is that, now with support of an appeals court, they’ve actually had permission to get into most of the government systems they wanted to. It’s not like the GAO, a government agency that is tasked with overseeing the affairs of the rest of the government, is doing this. These are basically private sector actors who work for Elon Musk and have private sector interests. And we simply don’t know what kinds of backdoors they left in these systems where that information could be updated with further downloads, now that DOGE is largely out of the picture. And it went into legal territory where it should really not have gone, shutting down USAID and closing entire agencies. One I’m particularly close to, the National Endowment for Democracy, had its complete funding revoked despite the fact that it, like USAID, had been created by Congress with money appropriated by Congress and so forth.

So that was one initial assault. That phase is winding down. The second phase had to do with so-called for-cause employees. There’s about 200 of them scattered through the U.S. government. A for-cause official is an official that makes policy—a fairly senior position. But the law says that you cannot simply fire them—you have to give a reason. And the reason has to be a fairly serious one like corruption or malfeasance that can at least be articulated and demonstrated. So, a number of these for-cause employees were fired. There’s a good reason for having for-cause employees because there are certain roles in the U.S. government that are technical, that are best done by nonpartisan experts. This includes the head of the Bureau of the Census, the Bureau of Labor Statistics. You have inspectors general scattered throughout a lot of federal agencies whose main job is simply to watch for corruption and malfeasance in different agencies—and these were summarily fired.

So, Congress created this, as well as these multi-member commissions like the FEC, SEC, ICC, and so forth, for good reasons—because it was felt that there were certain positions in the U.S. government that needed protection from ordinary politics, because they depended on a kind of, if not nonpartisan, at least balanced-partisan oversight. And that’s why you had multi-member commissions and for-cause employment. The conservatives on the court had been gunning for this for a good long time under a theory of the unitary executive, where a single person in the executive branch, the president, should have the ability to fire basically everybody across the U.S. government.

We’ve seen the effects of this. This was actually supported by a Supreme Court decision in the 1930s called Humphrey’s Executor, the right of Congress to make rules like this to make it more difficult for the president simply to take these officials out. That’s been under a lot of pressure. They have not invalidated it yet. I suspect that they will next year when they take this matter up. The thing that stopped them in this particular instance was the Federal Reserve, because even the conservative supporters of President Trump understood that the independence of the Fed was something that the markets really, really cared about. If you remember, on “Liberation Day,” when they first broached the idea that Trump would get rid of Jerome Powell, the markets reacted very, very badly to this. So the conservatives on the court had this dilemma because they wanted to get rid of Humphrey’s Executor, they wanted to give the president permission to get rid of any senior official he wanted to—but they also didn’t want to make it seem like they were empowering him to get rid of Jerome Powell and the rest of the Federal Reserve. They are going to take this up again next year. I suspect that, since Powell’s term is up next year, Trump’s already had the ability to appoint new governors. He’ll have more of that by the time Powell’s term ends. And I think it’s going to be kind of a moot problem next year. I think Humphrey’s Executor will be gone and the precedent that the president can fire any of these officials he wants at-will will be established.

“So, I actually like the deep state. I think that any functioning political system has to have a civil service that meets these basic Weberian requirements of being nonpartisan, expert, professional. That has really been the target of this current administration; a lot of Project 2025 was really about what they would do to the so-called deep state. One of the deepest political characteristics of American culture is distrust of government—so this is nothing new. But the ferocity of this particular attack is quite unprecedented.” — Francis Fukuyama

The final thing is what’s now called Schedule G. At the end of the first Trump administration, they issued an executive order creating a new Schedule F that basically put the entire Federal civil service on at-will status. That was rescinded immediately by the incoming Biden administration, but it’s back now. It came back first as something called Schedule PC and then they posted a new version of it called Schedule G, which expands the ability of the president to remove federal officials beyond these very senior at-will officials to basically everybody in the federal government. This puts the country back to where it was before the passage of the Pendleton Act. In the 19th century, beginning with our first populist president, Andrew Jackson, every post in the federal government, every fourth-class postmaster, was a political appointee. And every time there was an election when the parties changed positions, as they did almost every two years in the period after the Civil War, almost every federal employee was fired and replaced by a candidate who owed his position to political patronage, to one of the two political parties. This was ended in 1883 by passage of the Pendleton Act that, for the first time, required a civil service examination and put the civil service on a merit basis. This took until World War I to become generalized throughout the U.S. government because Congress really did not want to give up its power of patronage. So it was a very gradual process.

Even before Trump got there, we still had about 4 or 5,000 so-called Schedule Cs, who were political appointees, which is about 4,000 more than in almost any other modern democracy where you have a professional permanent civil service. So we retained more of the patronage system even before Trump, and now they want to get rid of the whole thing. So, yes, your fourth-class postmaster will flip over if there’s an election that brings a different party to power. And I think the problem there is different because it basically is going to bring back opportunities for massive corruption. That’s what the patronage system in the 19th century was characterized by. That’s when you had all of these big city machines like Tammany Hall in New York. And with this ability to fire any employee of the federal government, the incentives for politicians to use that power to reward supporters is going to be very great.

Wittes: I want to ask you very briefly: Connect all this to the word “liberalism.” Because it seems like what you’ve laid out is a sea change in constitutional politics, maybe some really bad policy and opportunities for corruption. But what’s illiberal about it, exactly?

Fukuyama: What’s illiberal about it really has to do with rules. Liberalism—my definition of liberalism—has to do with the rule of law and constraints on the exercise of executive power. And what Congress was doing by creating these different rules for federal employment was to put constraints on the power of the executive to simply do whatever that person wanted to do. I think that by turning all of this into a policy decision, it has eroded those kinds of checks.

Quite frankly, in Trump’s first term, the federal bureaucracy was a check on a lot of the things that he wanted to do. They simply slow-walked, for example ... I mean, now we’re in the midst of the National Guard coming into Washington, D.C.—he wanted to do that back in the first term after the George Floyd protests. And he was stopped from doing it by a bureaucratic structure that was slow-moving and resisted him and had the power to do it because a lot of the officials that were put there were chosen for professional background, for neutrality, and the like. And now, that’s going to be gone.

Wittes: Ruth, Jack, responses or thoughts?

Jack Goldsmith: On this question of Humphrey’s Executor, this very important Supreme Court decision about constraints on the president’s power to fire senior executive branch officials who have certain protections from Congress, the court has been attacking this precedent for a long time. Trump is not the first president to rely on this diminution of power to fire independent agency heads. That honor goes to the Biden administration, which did it in reliance on this precedent in many contexts. Trump is turbocharging this, obviously. Humphrey’s might be overruled—I’ve actually been surprised by how ambiguous the court has been in its interim orders about whether it will do that. There’s still many constraints on the president’s constitutional power to fire executive branch officials, even if Humphrey’s is overruled. So, I don’t think that the president is going to have free constitutional reign to fire every executive official just by the overruling of Humphrey’s.

But one of the many things I’ve learned this year is that the president has many better legal arguments than I ever appreciated for winnowing out and firing members of the executive branch. Not on the basis of some constitutional power, but rather simply relying on the various statutory schemes that have many ambiguities and loopholes and that have largely been regulated by norms. And, of course, if there’s a norm in the room, Trump is going to sniff it out and violate it.

So, a lot of what’s been going on for most of the clearing out of the bureaucracy has not been an exercise of constitutional power, but has been these down-in-the-weeds legal arguments where it turns out Congress did not do the greatest job in ensuring that the president didn’t have the authority to do what he’s doing.

Wittes: And, of course, the merits of those cases, of which there are literally tens of thousands, have not yet been approached because most of them have to go through the Merit Systems Protection Board, which doesn’t have a quorum right now.

Ruth Marcus: What’s going on in the executive branch right now and the assault on the deep state—and I say this as somebody who’s just finishing up a long profile of Attorney General Pam Bondi, so I’ve been looking a lot into what’s going on at the Justice Department in terms of the firings, and this president’s assertion of authority, leave aside Humphrey’s Executor, which applies to a very small number of people, and leave aside the independence of the Fed—this administration is just willy-nilly asserting the authority under its alleged Article II power to fire anyone for any reason at any time, law be damned. And there are some folks in this audience who have been the victim of this kind of firing, which pays no respect whatsoever to the rule of law. That is the situation that we are living under right now.

Wittes: I’m just curious if I can get the two of you to agree that there are some firings, for example, the firing of Maurene Comey, the prosecutor in the Epstein matter, who is ...

Marcus: I’m sorry, what did you say her last name was?

Wittes: Comey, yeah. The only authority cited for her firing is Article II of the Constitution. It doesn’t cite one of these esoteric loopholes.

So, on the one hand, you have stuff that represents an extraordinary power to reach down into the career bureaucracy and just get rid of anybody you don’t like. And, at the other end of the spectrum, there are RIFs—reductions in force—that are probably lawful, if distasteful. There are people—for example, FBI agents—who do not have the degree of civil service protections that exist in some other agencies. So, as you litigate this broad range of civil service decimations, you’re going to have a variety of different outcomes.

Fukuyama: I think there are three categories of bad things that are happening. One are unconstitutional things—like birthright citizenship. Then there are things that are illegal where you’ve got a statute that says you can’t fire somebody except under these conditions. They violate that. And then there’s a big category of things that are just bad governance. And I actually think that most of the really bad stuff has been in that third category.

For example, among the people that they went after first were probationary employees. Now, this is just some factual background: The U.S. government has roughly the same number of full-time employees today as it did in 1969. The size of the federal government has not ... I mean, it’s just a conservative myth that the government’s just grown by leaps and bounds. It actually processes about four or five times as much money as it did in 1969. But many federal agencies are really, really strapped. They’ve got a really big problem in getting young people, especially tech-savvy young people, to come into the federal civil service. The average age of a civil servant is somewhere in the high 50s. This is not the kind of government you want to deal with artificial intelligence and all the changing social conditions that we face. And it’s probationary employees that are these young people that made a big effort to get into the government, and they’re the first to go. So that’s bad governance—maybe perfectly legal, but it’s really bad governance.

Wittes: My point here is simply that, as these things get adjudicated over the next three to five years, you’re going to have, within the civil service decimation, a pretty wide range of outcomes. And I’m just trying to figure out if that is a point of common ground between Ruth and Jack.

Goldsmith: I agree with the way you describe the situation.

Marcus: Sure, yeah, probably where Jack and I disagree most vividly—and we’re friends, so it’s an energetic and fun disagreement—has to do with what happens in the interim period.

Wittes: Yes, but let’s come to that in a moment, because I’m about to ask you a question that’s going to tee that up for you, Ruth.

“The Supreme Court majority may not have the same conception of the president’s Article II authority that President Trump has, but it’s a pretty capacious vision of it. And when you combine its hesitation and unwillingness to intervene to stop the president in the interim with its broad conception of Article II authority, that is what interferes with my sleep.” — Ruth Marcus

All of this stuff ends up in the courts. Congress is dealing with exactly none of it. That puts an enormous burden on a set of institutions that likes to congratulate itself for passivity as a virtue. The performance of the courts over the last six months has been extremely variable by level of court, by individual judge. So I want to start with you, Ruth, on this: How do you assess the performance of the courts in relation to the question of liberalism and illiberalism in this moment?

Marcus: I think I want to fight the question—not the hypothetical, but the question. And for this reason: I don’t think we can assess the performance of the courts in a vacuum. I think we have to assess the performance of the courts in context. Jack will probably disagree with me about that, because the courts maybe shouldn’t pay attention to what’s happening in other branches or in outside society. But I can, and I do. And the courts are operating in a sphere where there’s been a complete systemic breakdown of checks and balances and the way things should operate.

So, you have law firms that are caving to outrageously unconstitutional edicts and therefore not stepping up to the plate to do the jobs that they would normally do. You have the media—much of it, not all of it, thank goodness—notably cowed by completely frivolous lawsuits, paying up millions of dollars and not doing its kind of constitutionally envisioned role. You have educational institutions anteing up enormous sums to make Trump leave them alone and scared about what they’re doing. That’s kind of external to government. You have one constitutional branch, Congress, that is completely absent from the scene, that provides very little, if any, check at all. You have a president who’s determined to exercise maximum constitutional authority.

I can’t tell you how many times I have written this sentence: This is not normal. But I also get to write this sentence: This is just flagrantly illegal. I mean, you can argue about Humphrey’s Executor or various things on the margins, but look at the firings of individuals—you have a system where people are fired; there are clear violations of the civil service law; they have to go to the MSPB, which is going to take forever, is non-functional, and doesn’t have a quorum to adjudicate these things.

So, to get to your question, you have to think about the courts within this system that feels to me—and I’m not usually such a hyperbolic, pants-on-fire type person—that the entire system is falling apart/falling down on the job. The courts, in this context, have been, not the least dangerous branch, but actually the most effective branch—but that may not be saying very much. And we also don’t know very well how effective they’re going to be in the end. If there is any institution that has performed well to date, it has been the courts.

But I have enormous concerns about two things, in the end. One is what the Supreme Court will and won’t allow the lower courts to do as these cases are making their way through the system. We’ve all heard about universal injunctions, and there are legitimate worries about lower courts overstepping their bounds. But there are also legitimate worries about an administration run amok and not hemmed in while these cases make their way through the courts. For example, I don’t lose any sleep, and I tell other people not to lose sleep, about birthright citizenship. I don’t think, in the end, even this Supreme Court is going to allow President Trump’s flagrantly unconstitutional executive order to stand. But a lot of mischief is happening, not necessarily in birthright citizenship, but within that process.

So, this court, for various reasons, is worried about exercising its authority—because if it exercises its authority too much, it won’t have its authority. But what’s the point of having authority if you’re never going to exercise it? I think it was Madeleine Albright who used to say, “What is the point of having these armies if we’re never willing to use them?” And that’s what I think about the court’s power.

The Supreme Court majority may not have the same conception of the president’s Article II authority that President Trump has, but it’s a pretty capacious vision of it. And when you combine its hesitation and unwillingness to intervene to stop the president in the interim with its broad conception of Article II authority, that is what interferes with my sleep.

Wittes: Jack, I think your sleep is less interfered with by the court than Ruth’s. Talk to us about the court’s performance as you understand it.

Goldsmith: Sure. So the first thing I would say ... Ben, you said all of it ends up in court. And, as you know, that’s not true. A lot of the illegal things Trump is doing can’t end up in court.

Wittes: I take that point. That is exactly right. But give us some examples of the things that don’t end up in court.

Goldsmith: So, the president is acting blatantly illegally by not enforcing the TikTok ban. Presidents have played fast and loose for a while in their discretion to not enforce certain laws. No president has ever just said, “I’m not going to enforce this law because I don’t like it.” That is blatantly illegal. It’s actually, arguably, one of the most clearly illegal things he’s done.

Wittes: And just to be clear, this is a law not merely passed by Congress, but upheld by the Supreme Court.

Goldsmith: Right. That’s one thing.

The open corruption ... he’s basically exercising his Article II authority. He’s basically said, “No prosecutions of any of this corruption stuff.” So he’s greased the wheels of that in a way that is never going to reach the court in this administration, and it’s going to be hard in a later administration.

Some of the stuff Ruth mentioned, which I put under the heading of extortion—the universities, the law firms—these things can make it to court, and they have, and the administration has lost every one of these cases in court. But it doesn’t matter, because we’ve learned that the extortion can still work—these are the settling law firms and the settling universities—even if you can win in court. Because, the administration, if it’s completely shameless and willing to use power extremely aggressively, can absorb the losses in court and still win. So that’s another example where the courts can’t save us.

There are many, many, many examples of things not reaching the courts, or reaching the courts, the courts doing the right thing, and it doesn’t matter. That’s the first point.

The second point is people have looked at the Supreme Court’s record. The Supreme Court has basically been engaging this in what’s called its interim orders docket. These are decisions about what the rules are going to be during the course of litigation. And the Trump administration has won most of these. So people look at this and say, “The Trump administration has won 15 of 18 cases”—or whatever the numbers are. “The court is in the tank for the Trump administration.” And I just think that is massively misleading. The court only considers the cases that the Solicitor General, the Justice Department agency that argues these cases before the court, thinks it can win, i.e., the weakest lower court decisions are the one the court is looking at.

And, frankly, I’ve looked at all 18 of these, you can argue many of them, but the court has not, in my judgment, done anything obviously wrong in any of these cases. It’s also stood up to the administration in some areas where it really matters. More importantly, in putting this in context, there are literally dozens—by my count, it’s hard to count, but four to six dozen— injunctions by lower courts against various things that the Trump administration has done, which are being complied with, which the government has not sought interim relief from, and which are basically having an impact in slowing down what’s going on.

Two more things. First, the courts have to comply with the law. They can’t just pick up the vibe that the president’s out of control and start pushing back. They have to pay attention to the law. Now, we can debate about what the law is and what the president can do, but they can’t just respond to the vibe and push back against the president, because they have to ground it in law.

Here’s the really important thing: The court, without the support of the Congress and without the support of the executive branch, is simply not as an institution, in part for the reasons that many of these cases can never make it to court, and in part because the court does not have sword or shield, and has always been in this precarious position vis-a-vis the executive branch, going back to Marbury v. Madison, the most famous decision in Supreme Court history, where John Marshall took a dive in that case because he was worried that his decision wasn’t going to be enforced ... the court is always in this precarious position vis-a-vis the executive. And if we think that the court is going to save us from President Trump, that is just a massive mistake. It’s not going to happen for all those reasons.

Wittes: I want to ask you about the issue that Ruth raised earlier, which is, she doesn’t necessarily disagree with you that, on some of these big cases, the court’s going to end up in a good place. But there’s all this mischief that happens in the interim; there are the issues that Frank raises. It turns out you can actually destroy an entire federal agency just by reductions in force or firing all the people in it. It turns out that you can take away citizenship from a lot of people—or at least you can try—between the time your order goes into effect and when the Supreme Court says what we all know it’s going to say. So, my question is: How tolerant should we be of the court being—and I concede right up front that this is its traditional posture—let things ripen, let things percolate in the lower courts, wait till there’s a conflict in the circuits, don’t rush to rule on anything.

But there’s something that moves me, frankly, when Ruth lists all the institutions that are not doing their jobs, and saying, “Hey, this thing is before you on an emergency order.” The failure of everybody else is actually worth some measure of urgency on the court’s part.

Goldsmith: I would just point out that most of the things Ruth mentioned aren’t before the court. The law firm issue hasn’t come before the court.

Marcus: It’s coming.

Goldsmith: It’s coming, and I have zero doubt that the court will rule against the Trump administration on that. The universities as well. So, let me just contextualize the point. What you’re basically saying is: The court has, without fully blessing what the administration has done in the 15 cases it’s looked at, allowed the administration to proceed for one or two years, during which period massive damage can be done, no matter what the court decides.

Marcus: Massive, irreparable damage.

Goldsmith: Yes, massive irreparable damage, no matter what the court does.

Wittes: And it has linked that—sometimes explicitly, sometimes not explicitly—to a probability of success on the merits.

Goldsmith: Yes, right.

Wittes: Implying that, when it comes time to it, we may actually say, “This is fine.”

Goldsmith: I think, implying that we’re probably going to say it’s okay. But all I can say is that this is a cost. The court is not a perfect institution. It’s a “reactionary” institution. It has rules. It is the most reactive of the three institutions of government, and it has many constraints. On the merits of those cases, there’s not a lot to obviously disagree with—but I acknowledge that this is a massive cost.

To put it in perspective, because the court is allowing those things to continue, all these other things that have been slowed and stopped by the lower courts, the court is not looking at that because the Solicitor General hasn’t even brought it before it. So, we’re really looking at a massively skewed sample. And I think it’s kind of hard to get the full picture by just looking at the Supreme Court decisions without looking at the four dozen lower court injunctions against the administration, which, despite the early nonsense, are being complied with.

“The president is acting blatantly illegally by not enforcing the TikTok ban. Presidents have played fast and loose for a while in their discretion to not enforce certain laws. No president has ever just said, “I’m not going to enforce this law because I don’t like it.” That is blatantly illegal. It’s actually, arguably, one of the most clearly illegal things he’s done.” — Jack Goldsmith

So, all I can say is: the court is following its rules. We can argue about the merits of each case. We can get down in the weeds. Maybe it should have sent a signal in a couple more cases—go slow. I mean, these are non-legal calls that the court often makes. And maybe it should have done that a few more times. But I think, in the round, the court has been doing what it should be doing.

Wittes: Your point is well taken. And just as an example of it, Jack is speaking in big, round numbers here—“dozens of injunctions.” One of them involves the case that Frank mentioned earlier, which is the National Endowment for Democracy case, which there was a ruling in the other day at the lower court in which the district judge basically said, “I don’t believe this is not a political interference, and you need to give the NED its $97 million.”

Goldsmith: Is this the Dabney Friedrich opinion?

Wittes: Yeah, so, Dabney Friedrich is a superb judge, in my view.

Goldsmith: And she’s a Trump-appointed judge. I read this opinion. It’s a completely convincing opinion. I expect that this is not one the Solicitor General is going to be fighting.

Wittes: Just today there was a status report in which the government did not mention that it was appealing, which I take it to mean that it won’t, and it did say it was going to obligate the funds in an expeditious fashion. The interim statuses can be quite variable.

Ruth, I don’t want to leave this stage without talking a little bit about the press. For those who don’t know our respective professional histories, Ruth and I worked together as Washington Post editorial writers for a long time. Over the last three weeks, we have seen a mass exodus from The Washington Post of people with, I would say, longer than X number of years of experience there. I don’t know whether Ruth would agree with this term, but it’s death spiral-like. So, Ruth, I’m interested in your thoughts on the state of the press in general—you yourself have left the Post recently, although not as part of this particular wave—but also the state of the press more generally.

Marcus: So, not all of the problems with the press are Donald Trump’s fault. We have a business model that was collapsing, separate and apart from Donald Trump. But he has not helped matters. I think that the capitulation of entities like CBS, apologizing and settling a lawsuit involving its decisions about what to quote from an interview—this is an interview with Kamala Harris on 60 Minutes—when the quotes were entirely accurate and fair, and the notion that you would pay money to settle this suit because you want to get your merger approved by the authorities, is ... there’s just no adjective that could be strong enough to describe this. The notion that ABC would settle a bogus defamation claim involving the fairly accurate description of what the president did in his private life to a woman is just another example of the fear that he has put in people. And I think Jack made a really important point that Trump was going to ultimately lose these lawsuits, but it didn’t matter because he won by filing them. Trump is going to ultimately lose in his efforts against law firms, but it doesn’t matter because he has cowed them by threatening to put them on his little blacklist.

Look, the Post specifically and the media generally is still doing what it is instinctively, institutionally supposed to do, which is covering rigorously the Trump administration as it’s supposed to cover all administrations. But the combination of this punitive environment and the disintegration of the news cycle has caused woe, not simply for The Washington Post, but across the industry.

And I spend most of my year these days living in Wyoming, where I think about somewhere between a dozen and 19 local newspapers have, all of a sudden, because they were owned by the same conglomerate, shuttered their doors. If we do not have functional press, if we do not have functional local press, if we do not have functional national press, corruption is going to thrive. The framers understood that you cannot have a functioning democracy without the sunlight and reporting that’s necessary for it, and we should all be very worried about these things.

And, honestly, I have to say, if Donald Trump were to recede from the scene tomorrow, my degree of worry would not be greatly lessened.

Wittes: Yeah, I agree with that. Although there are a few areas where it would be lessened, and one of them involves the institution of the Voice of America, which brings together Frank’s point about the sort of drive-by destruction of the federal workforce, with Ruth’s point about journalism.

We recently posted a job at Lawfare, and the unbelievable number of VOA formers who applied for it with incredibly refined expertise in very specific parts of the world was just heartbreaking, actually.

I don’t know if that’s fundamentally a media story or fundamentally a destruction of the federal workforce story, but it’s an awful, awful situation.

Fukuyama: Could I ask a question of my fellow panelists?

Wittes: By all means!

Fukuyama: So, Jack and Ruth, you both refer to the weakness of a lot of the cases, and I assume that’s because what Trump is trying to do is extortion, essentially, right? That university has a contract to do cancer research with the federal government, and the government is canceling that because of antisemitism, right? And that’s why the government is going to lose if they take it to court. Why are [those that Trump has targeted] so afraid to pursue these things, then? Why are they settling early if they really don’t have a legal basis?

Goldsmith: For the same reasons that you had a split among the law firms. Some of the law firms fought, and they’ve all won in court, and they got their formal legal protection. And then some firms settled, and they’re in many ways in a worse position. But the ones that got their formal legal protection, it doesn’t matter—the Trump administration can continue to impose pain on them through informal means by just, on the sly, not hiring any of their clients to do federal government work.

Fukuyama: What about universities?

Goldsmith: It's the same with the universities, I think. I’m not an expert on this, and Harvard won its injunction when it went to court, but the Trump administration has endless tools in reserve—it recently went after its patents—to continue ratcheting up the pain. And, again, I’m not speaking for Harvard, but Harvard can fight these things legally—but, ultimately, even if it wins in this round, it’s going to end up losing in the politics in the next round. So, I think the universities want the pain to go away.

I wrote a book about the mob, and this is the way a shakedown works. You bring illegal pain on someone, and they settle because they want to lessen the pain, even though it’s illegal. And the government, it turns out, when you really weaponize it, can bring round after round after round of pain against you. That, in a nutshell, is the way I think it’s working.

Wittes: Yeah, and that has immense implications, just to go back to the name of the panel, for liberalism.

Ruth, you have a Pam Bondi profile coming out, as you mentioned. The pointy end of the spear in any effort to weaponize the government is the Justice Department, both because, in an offensive sense, it prosecutes cases and investigates cases, but also because, in a defensive sense, when you shake down Harvard University and Harvard sues you, it is the Justice Department that is going to defend that.

My general impression is that the magnitude of the changes in the Justice Department are breathtaking, and it is very hard to overstate how impactful the last seven months has been. Particularly at the FBI, it is much worse than is public. There are large parts of the Justice Department that are decimated of personnel and, frankly, there’s an inverse relationship between the quality of the personnel and the likelihood that they’ve left or are leaving. I’m curious, in your reporting for this story, is it any better than my admittedly hyperbolic characterization?

Marcus: Oh, it’s so much worse. You’ve completely understated it because it’s not just the hollowing out of the department. I think 70% of the Civil Rights Division is gone. Half the career lawyers in the Solicitor General’s office are gone. Half the lawyers in the office that defends the federal government against these lawsuits are gone at precisely the wrong time for the administration.

Wittes: ... And Jack’s old office.

Marcus: The Office of Legal Counsel, which gets to the point: It’s not simply the hollowing out and what that means ... by the way, in the next administration that comes—because there will someday be a Democratic president elected—what does an attorney general in a Democratic administration do? Does he or she then purge the people who have burrowed in in that administration? Are we just in this endless cycle of retribution?

“The capitulation of entities like CBS, apologizing and settling a lawsuit involving its decisions about what to quote from an interview … when the quotes were entirely accurate and fair, and the notion that you would pay money to settle this suit because you want to get your merger approved by the authorities, is ... there’s just no adjective that could be strong enough to describe this. The notion that ABC would settle a bogus defamation claim involving the fairly accurate description of what the president did in his private life to a woman is just another example of the fear that he has put in people. … Trump was going to ultimately lose these lawsuits, but it didn’t matter because he won by filing them. Trump is going to ultimately lose in his efforts against law firms, but it doesn’t matter because he has cowed them by threatening to put them on his little blacklist.” — Ruth Marcus

But it’s so much worse than that because the Justice Department has always, in Republican and Democratic administrations, occupied a complex and shifting role where it is the job of the Justice Department to be an advisor to the president, which means giving legal advice not just about what you can do, but about what you can’t do, and what the requirements of the law imposes on you. This Justice Department conceives of itself in an entirely different way: Its job is simply to achieve the goals of the administration, no matter what. The president was frustrated by his first attorney general, [Jeff] Sessions. He was frustrated by his second attorney general, William Barr. He picked Pam Bondi for a reason. He is getting what he wanted, which is: full steam ahead. There are no people at the Justice Department telling him, “Mr. President, you really can’t do this,” because they wouldn’t last if they did. And that is another really important internal constraint that is gone.

Wittes: I’m going to give Frank the last word. But before I do, Jack ... so, one thing that you all should know about Jack Goldsmith is that he has trained half the Justice Department. And he is an exceptionally beloved teacher. I cannot tell you how many people come to me and they know me as the guy who did Lawfare with Jack. You have a lot of contacts in the Justice Department from students there. Is Ruth overstating the matter?

Goldsmith: No, she’s not. In fact, I would say it’s even worse than Ruth described. It’s basically like an atomic bomb dropped on the Justice Department. I want to underscore something Ruth said: There are tens of thousands of lawyers in the executive branch, spread out, whose job is to ascertain the massive array of laws that’s supposed to govern executive branch behavior. And you can be cynical about this system, but it always worked, including with the Justice Department, in keeping the White House and the senior executive agencies more or less within the law, with some exceptions. And this administration has systematically and ruthlessly and successfully eliminated, with one exception, all internal legal resistance. It is simply not acceptable to offer an opinion contrary to the one that the president, who is not a lawyer, wants to push. It’s really an extraordinary thing.

The exception is the Solicitor General’s office. This is an amazingly interesting fact: The Solicitor General is the branch of the government that argues before the Supreme Court. And it has a very conservative Solicitor General. But the Solicitor General has quite clearly told the White House: We have to play different and play nice with the Supreme Court. And they have been playing different and playing nice with the Supreme Court, in ways that are not on board with the way the rest of the Justice Department works. And it’s a remarkable testament to how important the court is seen even by the Trump administration. So I know that there is independent judgment being brought to bear in that office. But the rest of it has been decimated in terms of personnel and in terms of independent legal judgment.

Wittes: Frank, you get the last word.

Fukuyama: I just want to expand on the point about what the next administration, a Democratic administration, will be faced with. Because you’ve got a live case of this in Poland right now. A little less than two years ago, a liberal coalition ousted the PiS—this Law and Justice populist party—and they’ve not been able to deliver on their agenda because there are too many PiS people that have burrowed into the bureaucracy, into the courts. They can’t get rid of them. And it’s going to lead to the PiS coming back, because people are saying: You promised that you do all this stuff and you’re not delivering on it. We’re going to face that same thing here, I think.

Wittes: You will hear a lot of great panels during this conference. You will not hear one with deeper expertise about the way the federal government works, has worked over the last eight months, and the way the justice system has responded to it.

Question: I’m a regulatory lawyer and I really appreciate your conversation. The bit you talked about at the end is well documented—it’s called “jawboning,” the ability to use weak claims of legal authority to achieve great effect. Jack did a good job of summarizing it. It’s the link between liberalism and the rule of law. When the administration can weaponize the legal system to get what it wants by making claims, by bringing lawsuits, the rule of law doesn’t exist anymore. But my question is about the dimension of this that we haven’t talked about, which is how Congress should respond. So I’d like to hear your thoughts about what you would suggest the Democrats do if they are able to take Congress. What legislation should be drafted to respond to the problems of the undermining of the independence of regulatory agencies and particularly to focus on the things people have taken for granted?

Wittes: Jack wrote a whole book with Bob Bauer about remedial legislation. What’s one piece of remedial legislation, from each of you?

Goldsmith: I actually wrote a whole book with about 60 different proposals in response to Trump 1.0. First, it’s hard for me to imagine Congress engaging in serious legislative reform. It’s just hard to see how we get there. In the last four years, there were a lot of people yelling and screaming that this was coming and you should do something. No one was interested. Obviously, legislation can help in some areas, especially with some of the corruption, which is very under-regulated by design and needs to be fixed. Maybe that’s where I would start.

But this is a problem that goes beyond what law can fix. The lesson I’ve learned in the last 10 years is the extent to which—and I’m sorry to use this word—it’s really non-legal norms that are kind of part of the working operation of the government that can’t be legislated easily. So I just don’t think there’s anything close to a silver bullet. I mean, it would take a long, long list of reforms. The pardon power needs reforming.

Marcus: In the aftermath of Watergate, we enacted a whole slew of changes that were designed to prevent a repeat. Almost all of them over the years or recently have been defanged and disestablished and it is really hard to imagine a Congress in the current environment that’s willing to take up that task in any meaningful way, I’m sorry to say.

Fukuyama: This is why Humphrey’s Executor is so important. If the court actually overturns Humphrey’s, it doesn’t matter. Even if Congress could agree that they wanted to limit the executive, it wouldn’t be held constitutional. So it’s a meaningless discussion.

Wittes: I disagree with all of you. I’m going to be the ray of sunshine here. There are three things that a Congress coming in can do, and none of them involve legislation.

The first is appropriations. Ninety percent of what Trump is doing can be stopped dead in its tracks by an appropriations committee that gives a shit. The second is investigations. Investigations are a non-legislative function of Congress. The House of Representatives in the first Trump administration did a heck of a job with investigations. The Ukraine investigation was a very, very serious piece of work, done with no executive branch cooperation, under difficult circumstances. We learned a lot from it. And the Jan. 6th committee, which was created in the House of Representatives—everybody’s forgotten the name Liz Cheney; you shouldn’t—was an amazing accomplishment that she and Bennie Thompson and the others did. It was really a terrific piece of work. And the third is impeachment. It bothers Donald Trump a great deal that he’s been impeached twice. And it was an important moral statement both times.

So congressional action ... it is not the perfect branch of government—it’s never going to be. But I want to resist the sort of Debbie Downerism on Congress, particularly about the House of Representatives, which vacillates between extremities but is capable of doing great things.

Question: I grew up in Canada and I’m a Canadian citizen. I moved to the U.S. 40 years ago and became an American citizen. I live in Detroit at the moment. Should I throw all my stuff into a truck and drive through the tunnel?

Fukuyama: Well, no. The single biggest check we have is an election. And there are a bunch of elections coming up. That’s the one thing that can really put the kibosh on all this illegal activity. So, no, I would definitely not go back to Canada. I would stay here and vote. And I’d persuade all your friends, and your friends’ friends, to vote.

Question: Since you’re talking about civic morale and some of the norms that undergird the system, I’m wondering if you could say a little bit about the morale among lawyers and the legal community. My interest in this question is because there’s so much turmoil in the intellectual movement more broadly, but it seems like the Federalist Society and lawyers more generally are not being swept up in that. I’m wondering if you could give us the temperature, the civic morale, among the legal community more broadly, not just in the DOJ.

Goldsmith: I can’t give you a good answer. There are a lot of lawyers in America in a lot of different communities. The split among law firms of those who have stood up to Trump versus capitulated to Trump is a massive fissure. The Federalist Society is very much on the outs of the Trump administration. They’re not nearly aggressive enough for the Trump administration, so they’re kind of being pushed to the side.

“There are three things that a Congress coming in can do, and none of them involve legislation. The first is appropriations. Ninety percent of what Trump is doing can be stopped dead in its tracks by an appropriations committee that gives a shit. The second is investigations. Investigations are a non-legislative function of Congress. The House of Representatives in the first Trump administration did a heck of a job with investigations. … And the third is impeachment. It bothers Donald Trump a great deal that he’s been impeached twice. And it was an important moral statement both times.” — Benjamin Wittes

In my experience, there is no single, coherent legal community. I have to say, the legal community has been largely silent in Trump 2.0. He’s done a good job of cowing them. And that’s happened in many, many contexts. But I can’t speak to what the morale is. I mean, there are many conservative lawyers who are on board with what’s going on in the legal community. So I don’t think there’s any simple answer to that question, I’m sorry.

Marcus: I think it’s a community that’s pretty traumatized. Whether you’re in a firm that capitulated or whether you’re in a firm that resisted or whether you’re in a firm that has kept its head down ... I think it’s hard to be a law professor in this environment. I think it’s hard to be a law student in this environment. I think it’s hard to be a practicing lawyer in this environment and say, “I would like to take on this client, but my firm doesn’t want me to. A judge has asked me to take on this case, but if I do this, I’m going to run afoul of things and I’m going to screw my partners and we’ll make a few million dollars less a year.” I think it’s a very difficult climate for lawyers.

Wittes: I will just point to a fact in one of Ruth’s articles recently: an excellent profile of Paul Clement, a conservative super lawyer who has taken on a number of really important cases in this environment and deserves a lot of credit. One of the things he did is an amicus brief at the request of the court in the Eric Adams case. This was when Emil Bove, whom I suppose we should now call Judge Bove, decided to drop this case in a pretty explicit quid pro quo for policy support from the mayor of New York. And the judge wanted to see whether there was any question about whether he had the authority to maybe not dismiss the case at the request of the Justice Department under those circumstances. According to Ruth’s story, the initial lawyer that he approached was unable to do it because, presumably, the firm refused to let him do it. So Paul Clement was actually the second choice. I cannot think of a previous case—I’ve been in this business a long time—where a federal judge comes to a big firm lawyer and says, “You’re a genuine expert in thing x, would you, as a service to the court, do an amicus brief?”, the lawyer is willing to do it, and the firm says no. I’m sure there are such examples. I can’t think of any. So, that’s one component of the atmosphere.

I want to identify one area where the morale is extremely high and the bar deserves a lot of credit, and that is the mostly-left litigating activist organizations. These are groups—there are some that are less political—that have really taken on an enormous amount of weight on their backs, often with firms helping them quietly in the background since the firms can’t put their name on anything, and sometimes without any help at all. I have spent a lot of my career doing battle with the ACLU—they’ve represented me in the last year. There’s a group of groups that have really overperformed, and I do think in those settings people feel very good about practicing law.

Question: You talked about both the weaponization of the government, but also the hollowing out of it. So I’m curious if you could explain how those two things go together.

Marcus: I think of them as distinct. We haven’t talked about weaponization enough. At the Justice Department, instead of seeming to resist Trump’s admonitions and exhortations to go after his political enemies, we’re seeing at least the incipient stages of launching investigations and convening grand juries. Just using the mechanisms of the criminal justice system in a way that has not been done since Nixon to go after political enemies. And that is very dangerous.

The hollowing out maybe involves people who won’t participate in that, who refuse to participate in it, and who refuse to defend it. If you don’t have people who are trained up in the way that they should behave, if you don’t have transmitters of the norms, then you don’t have effective norms. So, I do worry about the hollowing out as a long-term consequence, but I do worry about the weaponization as a very short-term and dangerous consequence.

Goldsmith: I just want to say one thing in response to Ruth, which will probably be very unpopular in this room. The Trump administration believes the weaponization did not start with the Trump administration. And they’re not without some basis in thinking that. I think this is hugely important to understand as a predicate to what’s going on now. I’m not saying that what’s going on now is justified. It isn’t. But there were some, in my judgment, bad decisions made in various contexts at the federal and state level.

“It’s basically like an atomic bomb dropped on the Justice Department. … [T]his administration has systematically and ruthlessly and successfully eliminated, with one exception, all internal legal resistance. It is simply not acceptable to offer an opinion contrary to the one that the president, who is not a lawyer, wants to push. It’s really an extraordinary thing.” — Jack Goldsmith

There is a tension because you need manpower to weaponize, but it turns out you can weaponize with not many resources. This has been a problem for the Justice Department. They’ve had all these lawsuits against them and they’ve hollowed out the Justice Department and they don’t have enough people to defend. So they haven’t been doing a very good job in a lot of these cases. But it also turns out that you can open an investigation with one person and ruin someone’s life. It doesn’t take massive resources to achieve consequential weaponization. But there is a tension there, I agree.

Wittes: It is also the case that some of the weaponization, particularly on the extortion side, is being done by people outside the government entirely. The call actually doesn’t have to come from the Justice Department.

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

This is an excellent and useful discussion. As a lawyer, I find the dilemmas excruciating. One point to add. It is said that "the federal bureaucracy was a check on a lot of the things that he wanted to do. They simply slow-walked, for example ...". I don't think that is correct, on the whole. What the "deep state" did was mostly just to enforce the law, to say, the statute doesn't allow this, or you have to follow the usual procedures. That's not slow-walking. It's not deep-state subversion. It's the rule of law. Ironically, the main law that the bureaucracy was enforcing and the administration was resisting was (is?) the Administrative Procedure Act, which was enacted in the late 40's as a Republican check on the potential excesses of the New Deal state. So they're actually fighting a prior Republican remedy for governmental overreach, one that has functioned reasonably well ever since. More basically, "deep state" is a bad term: I wish non-Trumpistanis wouldn't use it ... it came from the description of how the security services undermined the real, constitutional state in Pakistan, and is grossly inappropriate to describe how the Civil Service in this country is supposed to function. Let's not adopt one of Trump's lazy and mendacious slurs into responsible discourse.

Great discussion and it’s great that this panel has both left leaning and right leaning legal and political experts. I think the legal profession still has a degree of professionalism about it, even a conservative lawyer can argue for a liberal case. And I think that when the House flips to the democrats, the house will once again be able to make it tough for the Republicans to continue to enable authoritarianism!