Minneapolis Demonstrates How to Resist Brutality Without Losing Your Soul

It intuitively implemented the best teachings of liberal and religious traditions

“These are the times that try men’s souls.” That’s how Thomas Paine opened The American Crisis in 1776. The Declaration of Independence narrates the origins of that crisis: a tyrant choosing private gain over public good, usurping legislative authority, stifling immigration, cutting off trade, bending the judiciary, and sending “hither swarms of Officers to harass our people.” 250 years later, surveying the aftermath of the ICE surge in Minneapolis, we know what Paine meant.

We’re outraged. The violent deaths of Renee Good and Alex Pretti at the hands of masked federal agents shock and horrify us. Worse, they attack the foundations of American freedom. Liberal democracy requires that state power be limited, accountable, and answerable to law; that due process be sacrosanct; that enforcement remain proportional and transparent; and that when things go wrong, authorities are subject to credible review. That these constitutionally protected rights have been so brazenly ignored marks another dangerous turn for the American system of justice.

Much has been written about the social consequences of these threats. But we’d like to follow Paine in turning soulward. How do we bear witness and resist without letting our shock and outrage corrupt who we are? We’re not here to tell anyone what or how to feel. Rather, we want to explore two traditions of directing our feelings toward inner and outer peace.

Turning Resentment into Justice

First is a liberal-democratic tradition that rejects illegitimate authority and domination. Though most famous for his economics, Adam Smith deserves equal recognition for his Theory of Moral Sentiments, which argues that we naturally resent injustice and that sympathy with the oppressed drives our demands for justice. As Smith puts it: “Resentment seems to have been given us by nature for defence, and for defence only. It is the safeguard of justice and the security of innocence.” It is natural, Smith argues, to bristle at injustice and want wrongdoers to be punished. But we also realize that we cannot mete out justice ourselves. Our legal institutions must instead provide the kind of impartiality that we cannot. In other words: We can channel our resentment into making systems work for us, not against us.

We’re seeing that spirit play out in Minneapolis. Political institutions are responding: legal challenges are mounting to check ICE’s excesses; state and local officials are investigating the killings (and suing the federal government where they’ve been blocked); members of Congress are recollecting their power of the purse. All this is necessary; much more will be required.

But these aren’t the only institutions at work. Civil society has also mobilized: Community organizations and churches of all faiths staged a “Day of Truth and Freedom” that drew tens of thousands. Volunteers are delivering care packages to families who fear leaving their homes. The result: Against bitter winds and masked intimidation, Minnesotans are staging some of the most successful civil resistance of our lifetimes. They’re proving that the great strength of liberal democracy lies in providing a range of opportunities—public and private, formal and informal—to resist unjust authority without resorting to violence.

And this brings us back to Paine. If times like these try our souls, where can we turn for the emotional resources needed to sustain resistance in the weeks and months to come? The trouble, to paraphrase Adam Phillips, is that strongmen tend to bring out the strongman in us all. We feel ourselves being drawn to the anger and hatred that can itself perpetuate violence.

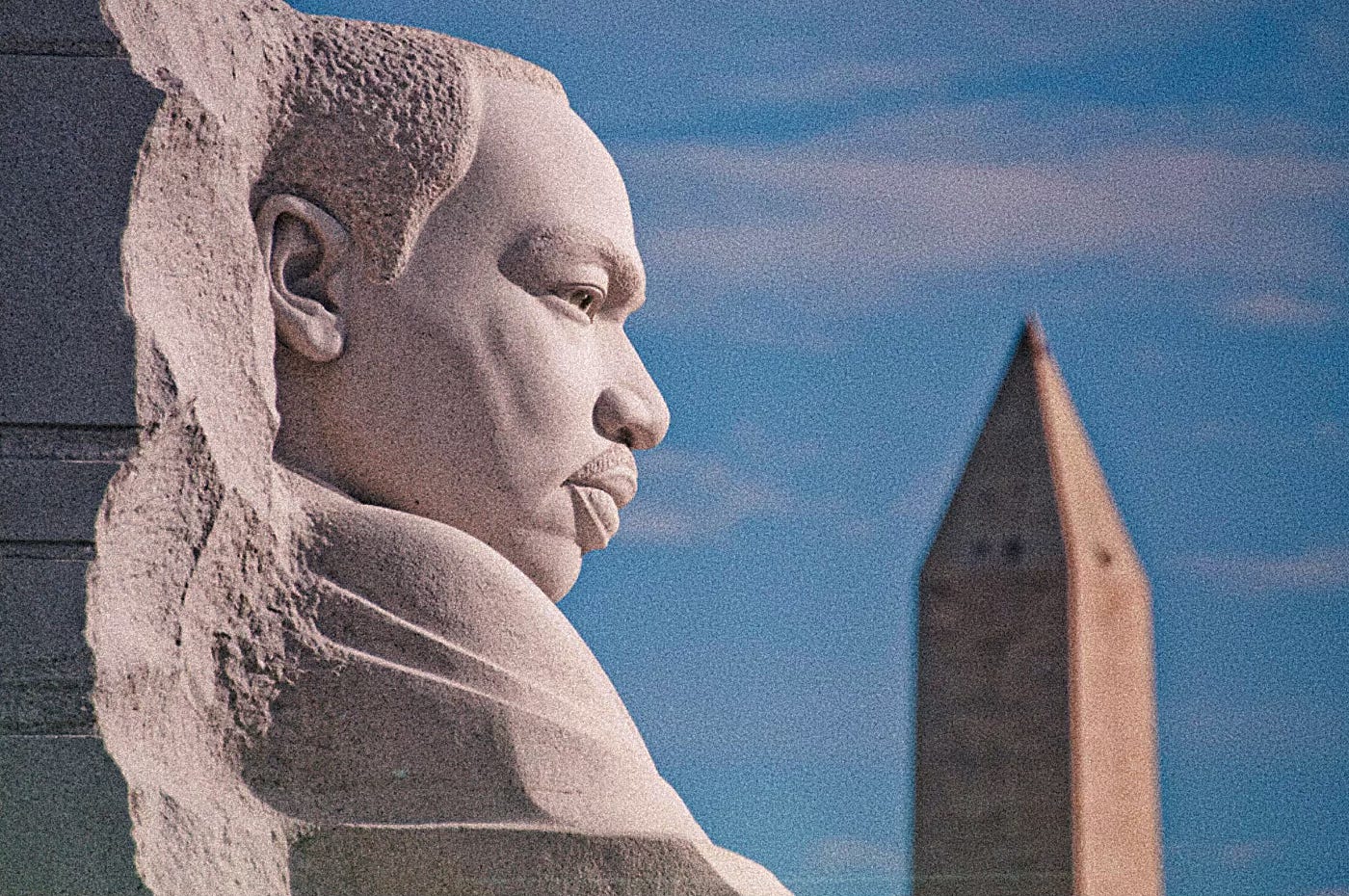

Compassionate Liberalism

Some liberals, such as Martin Luther King Jr., also point us to another, older set of traditions centered on compassion. In these, we seek the opposite of oppression. Against intolerance and xenophobia, we choose openness. Against fear, we bring hope. We learn that resistance begins with the hard work of overcoming our own worst impulses. As King puts it in Stride Toward Freedom, nonviolent resistance “avoids not only external physical violence but also internal violence of spirit. The nonviolent resister not only refuses to shoot his opponent but he also refuses to hate him.”

As social scientists, we’re struck by how these mental and behavioral practices also promote social goods. Consider Jesus’ famous admonition in the “Sermon on the Mount”: “Do not resist an evildoer. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also.” As theologian Walter Wink explains, to modern ears the centuries-old translation of antistenai as “resist” connotes acquiescence. A better translation, he suggests, is “Offer no violent resistance to one who does evil.” This not only better fits the context of preventing an “eye for an eye”; it also opens space for non-violent resistance. After all, Jesus had just finished praising gentleness, mercy, and peace. What are these if not resistive practices against evil?

King, for his part, found such virtues both morally and strategically necessary: “Christ showed us the way and Gandhi in India showed it could work.”

Buddhism offers similar disciplines. Practices of metta and karuna—goodwill and compassion—are directed toward everyone without exception, even those who commit atrocities. Extending a desire for wholeness not only to the victims of ICE harassment, but to the ICE agents themselves, recognizes that those who dehumanize others have lost sight of their own humanity. By nurturing compassion, we work toward restoring that insight in ourselves and others. This is not passivity. It is not absolution. It is, instead, a refusal to become what we resist.

Thankfully, these practices also provide a deep, restorative calm that can sustain resistance over the long-haul. Empathy—feeling another’s pain—can quickly exhaust us. Compassion draws on different parts of our brain and evokes warmth, concern, and care. It’s actually hard to hold onto anger while extending metta and karuna. Try it. Indignation in the face of injustice, yes—but not enmity. By releasing our simmering anger, we comfort ourselves and those around us and become more effective advocates for the oppressed. We also subvert the very hatred on which tyranny thrives.

The Long Arc of Resistance

In short, liberal and compassion traditions converge on the belief that we must allow ourselves to feel all the resentment that injustice demands while choosing—as so many Minneapolitans have chosen—not to follow these into violence.

All of this may sound hopelessly naive when extremists celebrate brutality. But most Americans want none of that. We want a society in which we’re free to pursue our own projects and purposes. We want governing institutions that can prevent harm without causing more. And then we want to get on with our lives. Here, too, Adam Smith got there first in noting how “the liberal plan of equality, liberty, and justice” leads to flourishing and peace.

Yet every generation learns that equality, liberty, and justice cannot be taken for granted. They must be reclaimed again and again from tyrants who believe that, under pressure, we’ll prove just as cruel and as rageful as they are.

Americans keep proving them wrong.

© The UnPopulist, 2026

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

When public opinion is STRONG, Trump knows he has to back down. It's time to call Congress (202 224 3121) and the White House (202 456 1414) about ICE reform. The next 10 days are critical. Read about the 10 Democratic proposals to curb ICE.

https://kathleenweber.substack.com/p/the-most-important-thing-you-can

I have been recommending Dr Gene Sharp's book From Dictatorship to Democracy for a very long time because it's all about nonviolent civil disobedience campaigns, and he talks about maintaining these attitudes in the face of violent governmental pushback, but very few people even bother to read it.