The Bogus Postliberal Indictment of Liberalism

Illiberal intellectuals engage in freeze-frame storytelling to blame liberalism for problems it didn't cause and is more capable of addressing than their alternatives

In two short years, Americans will celebrate the 250th anniversary of our Declaration of Independence. Given the challenges we face as a country, this landmark birthday has me wondering … are the liberal principles underlying the American experiment still guiding that experiment? And, as we ramp up our A250 plans, do we really get what it is that we’re celebrating?

On the first question, a sober assessment requires, well … sobriety. It’s important to recognize that relative to other places and other times, Americans are living lives marked by high degrees of political freedom, material abundance, and social equality. This is indeed worth celebrating.

At the same time, far too few Americans recognize these benefits—equality, material abundance, and social wellbeing—as the fruits of the liberal-democratic project. On both the left and right, many pursue authoritarian politics rather than liberal norms and institutions, as the route to improving their lot. Also worrisome is the surge of illiberal extremism, again, on both the left and right. A recent Reuters/Ipsos poll finds that 68% of Americans are concerned that extremists will engage in violence if the upcoming presidential election doesn’t go their way. While the motivation behind the recent assassination attempt on Donald Trump is not yet known, the fact that it happened reminds us what’s at stake.

As troubling as illiberal extremism is, however, the rising influence of a more erudite illiberal movement—let’s call it the “postliberal intelligentsia,” or PLI for short—is just as, if not more, concerning.

Who Are the PLI?

Among this cast of influencers are self-described postliberals, Catholic integralists, common good constitutionalists, and nationalist conservatives. Admittedly, the PLI is a diffuse crowd, with competing platforms and occasional infighting reminiscent of a scene from Monty Python’s Life of Brian. Despite their differences, however, the PLI is united by a single, overarching belief: The constitutionally constrained liberal-democratic order is the source of everything that is wrong in the world.

The list of grievances is long. Liberalism’s blind faith in individual liberty and autonomy, they argue, has devastated community and family life by pulling people away from their hometowns, delaying marriage and family formation, and making divorce too easy. Liberalism’s permissiveness has corrupted and stupefied America’s youth, compromised women’s traditional place within society, denigrated the moral status of masculine virtues, and degraded American culture through immigration from the developing world.

Most prominent is the movement’s forthright rejection of progress, which, they argue, has devastated the working class, fueled tyrannical corporate power, and sacrificed American economic interests at the altar of global trade. What’s needed to counteract these forces? According to the PLI, a new elite must emerge, one that sets aside the separation of powers, seizes the administrative state, and flexes its authority to impose political control over the economy and a pre-modern notion of “the common good” as the country’s governing ideal.

If none of this raises alarm, I get it. When we think of threats to an inclusive liberal democracy, we think of angry young men carrying tiki torches, the Proud Boys, and Jan. 6 insurrectionists. The PLI are not these guys. They are smart, bookish, (mostly) polite people with ideas. They do their organizing at conferences in glamorous ballrooms. Some hold endowed chairs at the country’s most prestigious universities. They are people with whom you might strike up a pleasant conversation after religious services or in line at the grocery store.

And that’s exactly the point. As concerned as we should be about the instigators of political violence, elite intellectuals aligned against core liberal principles are far more likely to move the Overton window in a way that accommodates authoritarianism in our day-to-day politics and culture.

And indeed, the PLI are gaining ground. They are internationally networked and have significant influence on the world stage. We’re seeing their influence in mainstream American politics, with the rise of nationalist conservatives in Congress like Josh Hawley and Marco Rubio, and the continuing influence of Donald Trump’s former advisor Stephen Miller on nationalist conservative immigration plans to “seal the border, deport all the illegals.” We’re seeing it with Trump’s decision to pick JD Vance as his vice president for a second term. And we’re seeing it in the PLI’s loose affiliation with populist right media figures like Tucker Carlson and Steve Bannon.

Liberal Rejoinders Are (Understandably) Incomplete

Public intellectuals—including William Galston, Stephanie Slade, Jonah Goldberg, Garrett Epps, Mark Lilla, Samuel Gregg, and others—have offered necessary and insightful responses to postliberal critiques of liberalism. But as good as these rejoinders are, when a liberal takes on the PLI, it’s like being on one side of the net in a tennis match facing a dozen opponents, all lobbing balls in different directions at the same time. A crushing response to a single complaint still leaves eleven others bouncing around on the court.

Part of the challenge is the gaslighting nature of PLI critiques. Is liberalism’s most important failing that it subordinates the church to secular politics? Is it that it allows too many goods, too much investment, and too many people from foreign shores? Or is its gravest crime that it allows Drag Queen Story Hour? It’s hard to tell. And just when you think you’ve nailed your response to one, the target changes.

But in fairness, another part of the challenge is that liberalism is, in fact, multi-faceted. Depending upon who’s making the case, liberalism may be championed as a political apparatus for constraining government power, or a set of rules aligning private and public interests, or as an ethos that favors reason-based inquiry and the open exchange of ideas. And running through all these facets of a liberal society is a moral philosophy grounded in the notion that each of us is the dignified equal of our fellow human beings.

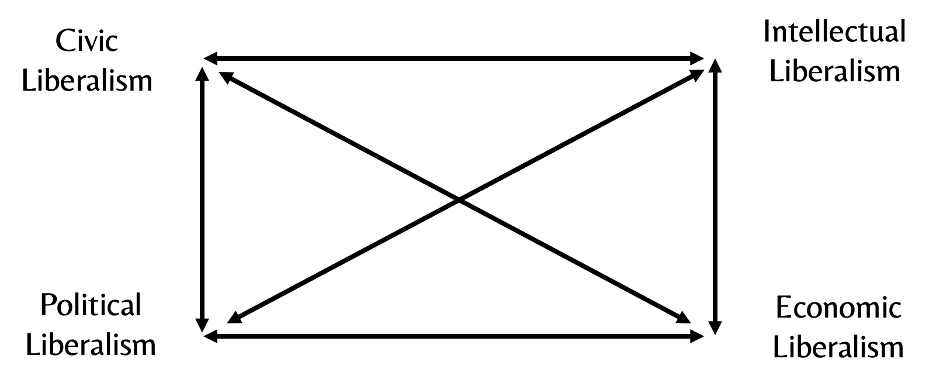

We should consider any capable defense of a single facet of the liberal project as a welcome contribution. And yet, any such contribution is likely to be incomplete. If we are to fully “get liberalism,” we have to see it as a coherent system that allows for experimentation and learning. And this means that occasionally we need to pull back the lens to see how its principal domains—political, economic, intellectual, and civic freedoms—work together.

Getting Liberalism In One Glance

To help “get liberalism” in a single glance, see the “Four Corners” illustration below. At each corner is one of the major domains of the liberal project. The double-headed arrows signify the dynamic relationships that exist across each of these domains.

The most familiar corner of the liberal project, political liberalism, emphasizes the institutional rules of the social and political game. Liberal rules constrain government power, check the power of majorities, ensure procedural fairness, and protect individual and minority rights.

Politically liberal rules of the game provide the baseline protections needed for the other domains to do their work. Political liberalism, for example, protects rights of property and enforces contracts, which in turn form the foundation of economic liberalism. Economic liberalism affords people the freedom to openly innovate, produce, collaborate, compete, and exchange with others in their commercial lives. And it’s this corner that has driven what economic historian Deirdre McCloskey describes as the “Great Enrichment” we’ve experienced over the last 250 years.

Similarly, political freedoms of speech and assembly provide the enabling conditions for intellectual and civic liberalism. The free and open exchange of ideas, scientific experimentation, and creative endeavor can only flourish if protections for speech and expression are guaranteed. Likewise, freedoms of association are necessary conditions if a civic liberalism—the arena of associational life in which we forge social connections both thick and thin—is to thrive.

But it’s not just political liberalism that supports the health of other domains. Economic abundance fostered within the economic liberalism corner sustains intellectual labors and accelerates discovery within the intellectual liberalism corner. Those discoveries, in turn, accelerate the pace of innovation and growth in the marketplace.

Such loops of reciprocal support illustrate a key feature of the liberal order: It is a system that learns and course corrects. As imperfectly liberal as the American founding was, the political freedoms that did exist—freedoms of the press, speech, and assembly (at least for some)—were key inspirations for emancipatory social movements that gained momentum through the essays, publications, oratory, and activism of leading abolitionists, and later, women’s rights, civil rights, and gay rights leaders. These intellectual and civic efforts, in turn, shifted the Overton window that eventually made liberal political reform possible.

Contestation Drives Social Learning

If there is a secret sauce that drives this learning, its primary ingredient is contestation.

At the core of political liberalism is the notion that government authority is contestable. By dispersing authority across the three branches of government, for example, each sphere of political power checks each of the others. The liberal marketplace too is an arena of contestation. The astonishing coordination we see in the marketplace is achieved not through top-down edict, but through the tugging and pulling of countless individual plans colliding with countless others.

Intellectual liberalism is also grounded upon the principle of contestation. Intellectual progress happens in the collision of ideas, but for that process to work, no one—no matter their title, role, or standing in society—can hold a special claim to truth that exempts them from challenge. Contestation also runs through civically liberal spaces, in which individuals and groups have the freedom to experiment with different ways of living, without the presumption that any particular group has the authority to impose its ways upon others.

And across all these domains, because there is contestation, there is experimentation. And wherever there is experimentation, there will be dead ends and wrong turns. But this is how liberal discovery unfolds.

This is perhaps easiest to see in the arena of intellectual discovery. When we want to solve a problem, we speculate, offer arguments, and run experiments. Any mature thinker knows that contestation—exposing one’s intellectual labors to the bright lights of scrutiny—helps us spot and weed out the bad ideas and sharpen the good ones. And through this process we become smarter. But it’s not just that individuals become smarter. Society as a whole accumulates and embodies—through continuous experimentation, learning, and fresh application—whole bodies of knowledge that no single person, no matter how smart they may be, could develop on their own.

And the same holds across the other domains of the liberal project. Every entrepreneurial endeavor is, in essence, an attempt to solve a problem. Many (if not most) attempts fail. But some succeed. And over time, through iterations of trial and error, entrepreneurs find the solutions that align incentives such that people unknown to one another can coordinate and get things done. (Through Uber, a stranger shows up at our doorstep and takes us where we need to go.)

Consider also the many civic lessons the liberal order has learned over time, lessons about how we can live together peacefully and productively, despite our differences. Interracial and same-sex couples can marry, raise children, put pictures of their spouses on their desks at work, and guess what? The world does not fall apart! These lessons may seem obvious today, but they were lessons that had to be learned.

In short, because liberal environments are contestable, we have the elbow room to try things out, make mistakes, adjust, and adapt. In the process, liberal societies have opportunities to learn, to become more consistently liberal over time.

The Liberal Promise Is a Society That Learns

But all this contestability, experimentation, and adaptation is precisely what the PLI want to avoid. It’s the whirling openness of liberal societies, they argue, that renders us victims of social and economic progress.

To drive these points home, PLI critiques often deploy freeze-frame storytelling. These freeze-frame narratives point to something bad happening in the world, tie that bad thing to liberalism’s fondness for individual liberty, and then propose a top-down fix (if they propose a fix at all). Because liberalism is the supposed cause of the problem, the audience is expected to set aside any liberal squeamishness they may harbor, such as concerns about individual rights, constitutional restraint, or market-based reasoning, as the PLI elect impose their conception of the common good.

Freeze-frame narratives are effective in the sense that they put any honest defender of the liberal project into a position of having to concede that (a) problems exist, and (b) solutions can be elusive. But where we agree that a problem does in fact exist, rather than responding apologetically or defensively, liberals ought to ask, “In which system will we have the best prospects of solving the problem?” Freeze-frame storytelling, intentionally or not, has the effect of foreclosing this line of questioning, and keeps us from understanding liberalism as a system that fosters learning.

The liberal promise is not that bad stuff doesn’t happen. Liberalism doesn’t promise that there won’t be economic or social disruption. What it promises is that with liberal norms and institutions in place, free people tend to find solutions. But when we reject liberal principles, workable solutions are much less likely to be found.

As America’s 250th anniversary approaches, we should not deny that as a country we’re facing serious problems. But those problems should make us all the more grateful that we are still living in a society that, because of its liberal foundations, is capable of learning and meeting those challenges.

The critical question is: Will that foundation survive the next 250 years? Or will illiberal remedies destroy the marvelous system that learns?

Emily Chamlee-Wright sits on the board of our parent organization, the Institute for the Study of Modern Authoritarianism. This essay was originally published in Persuasion, our partner publication.

Your "Bogus Indictment of Liberalism" was excellent...as far as it went. IMO our defense of liberalism needs to deal much more directly with the criticisms leveled at it, many of which are, I think, accurate. And I don't think you did that. Don't we lose something when community-based institutions fail? How's Liberalism going to address that? Are there things we stand for that are important in any society? Absolutely. Just saying that lots of individual experimentation is going to eventually fix everything doesn't quite do it.

from Fawcett: "For a liberal, left or right, the silence of liberal conservatism ought to worry them. That is true not just in Britain but in the rest of Europe and the US. Where are the speechwriters of the liberal right making sense of such turmoil, telling a convincing historic story of where we should be headed and what strategy would help us get there? They are there. They know the common liberal values they should be speaking for. Yet they have been silenced by the voices and vigour of the hard right. No convincing narrative with rhetorical appeal is on offer either from an equally confused and silent liberal left. Well-identified problems and intelligent offers for their solution abound in a troubled liberal world but defences of that world itself and its values are barely heard. They are spoken for in well-hewn essays, yes, but not crowed and shouted as they ought to be." © Financial Times Limited 2024.

Where, indeed, are the people speaking to "...the defense of that world and its values"? When "individual experimentation" tramples the values of that world, as it has done so much of late, those values, and our common world, are at significant risk.

I struggle to understand why this essay opens with both-sidesism about extremism and violence, as if there’s any comparison to be drawn. That unfortunately sets the stage for a discussion of PLI that fails to adequately acknowledge the extent to which it has embedded itself into the Republican Party, instead relying on vague abstraction to make broader points that, while defensible, ultimately don’t say all that much.

Because, I think, there should be plenty of room here for criticism of the extent to which the liberal project is indeed unresponsive to change and progress — see: the ever-worsening climate indices; rates of wealth concentration among the top 0.01%; The Supreme Court — but the essay speaks largely in models and hypotheticals, so a lively debate of specifics would be out of place. I suppose that isn’t the objective of this piece in particular. But then why open with a false equivalency, if you’re only going to prove its falsehood by going on to level criticism toward one side (the right side, to be fair (pun intended))?