The Neo Right's Multi-Front Revolt Against America

A political theorist traces the intellectual history of the various strains of a movement gone rogue

Book Review

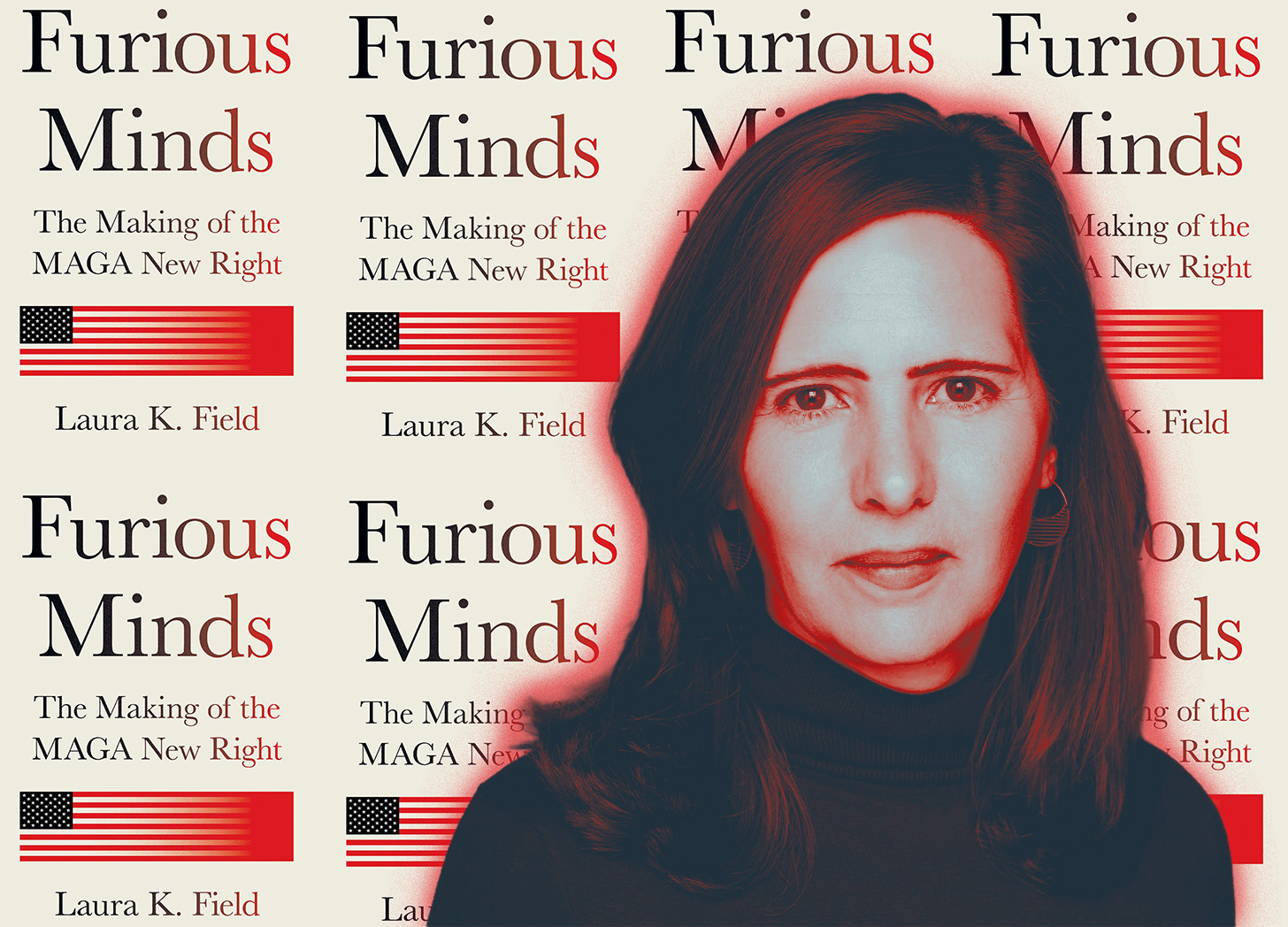

Although Laura K. Field’s Furious Minds: The Making of the MAGA New Right is not a short book, I found myself compelled to read it twice—one time for the ideas, the other time for the author’s story. As I discovered, they are related.

The book begins with a bang. A young woman, a 5th-year graduate student in political theory who is about to enter the job market, finds herself at a high-level academic conference. During dinner, one of the organizers remarks that he had recently attended a dinner with then-First Lady Michelle Obama and wanted to [expletive] her. The young woman excuses herself, goes to the ladies’ room, and asks herself, “What on earth am I doing here?” This began, she reports, the “long, slow process of extricating myself from the world of conservative intellectualism.”

This is how the two readings of her book come together: it is a deeply researched account of the rise of the MAGA New Right during the past two decades braided with the narrative of her break with it, a process sparked and shaped by what Field argues is the new movement’s increasingly blatant misogyny and obsession with masculinity. In an ending that closes the circle with the beginning, she could be described as a latter-day Athena soothing today’s Furies to rescue American democracy.

When I say “deeply researched,” I mean it. The book’s 59 pages of footnotes, set in type so small that my aging eyes could barely cope, bear witness to the extraordinarily persistent inquiry that informs it. This inquiry is more than archival; Field attended countless academic panels and New Right conferences (until the National Conservatives eventually barred her from entering) while tracking the online activities of leading New Right figures. The result is something rare—intellectual history that is not just researched but also reported, a vivid narrative that sweeps the reader along. You’ll really want to know what happens next.

The story begins in the 1970s, with the rise of the conservative “fusionism” pioneered by William F. Buckley Jr. and Ronald Reagan. It rested on three pillars—social conservatism, free market economics, and anti-communist internationalism—and it dominated the Republican Party well into the current century. It prospered in part because Buckley and Reagan policed its boundaries, barring extremists—Birchers and old-line antisemites, among others—from official participation.

Field does not spell out in detail the changes that undermined fusionism; here’s how I would fill in the gap. The fall of the Berlin Wall and collapse of the Soviet Union weakened conservative support for foreign policy internationalism, and the ill-advised long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan delivered the coup de grace. Free market economics included a disposition toward relatively open trade and immigration policies, but the negative consequences of globalization and a porous southern border called these commitments into question. While fusion-era Republican presidents always gave lip service to social conservatism, they never gave it the priority that its advocates craved.

After moderate Republican candidates lost twice to Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton became the favorite to succeed him, the revolt that had begun with the Tea Party during the Great Recession shattered the GOP’s “let us continue as usual” faction and led to Donald Trump’s improbable nomination as the Republican standard-bearer. His longstanding opposition to free trade, international commitments, and mass immigration soon came to dominate a radically changed party.

Nobody could accuse Trump of having a well-developed conservative philosophy, but his iconoclastic impulses opened the door to restless intellectuals vying to systematize his impulses into a New Right. Furious Minds tells their stories.

But this book is more than a compelling narrative. Because Field is a well-trained political theorist, she offers a lucid analytical template of New Right thought, along with penetrating analyses of some of its major figures such as Patrick Deneen, Yoram Hazony, and Adrian Vermeule.

She divides these intellectuals into four groups—the Claremonters, Postliberals, National Conservatives, and what she dubs the Hard Right Underbelly. The Claremonters, housed or trained at the Claremont Institute, drew their inspiration from one of Leo Strauss’ first and most influential students, Harry V. Jaffa, whose Crisis of the House Divided, a penetrating study of the Lincoln-Douglas debates, brought him scholarly renown. Field’s discussion provides reasons to doubt that Claremonters have remained true to Jaffa’s vision of the United States as a creedal nation dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Instead, as exemplified by Michael Anton’s famous “Flight 93” essay, they veered into a brand of anti-progressive alarmism that opened them to far-right extremism.

Unlike the Claremonters, the Postliberals do not believe that the United States was well-founded. Patrick Deneen became well-known for arguing that America’s founding creed—Lockean liberalism—led inexorably to a hyper-individualized way of life that dissolved the social bonds and traditional values needed for a decent and purposeful existence.

To fill the void liberalism creates, many Postliberals are drawn to “integralism,” usually inspired by Catholicism, that rejects the distinction between public and private life, state and society, and advocates a form of community guided throughout by religion. Some integralists embrace theocracy, while others are willing to settle for non-coercive persuasion toward a society suffused by a single creed. Harvard law professor Adrian Vermeule tries to bridge the gap between integralism and the U.S. Constitution with what he calls “common good constitutionalism.” Catholicism provides the substance of the common good, and promoting the common good, so understood, suffices to determine the legality of a law or action. Unlike legal liberalism, Vermeule writes, “[C]ommon good constitutionalism does not suffer from a horror of political domination and hierarchy, because it sees that law is parental, a wise teacher and an inculcator of good habits.” In this vision, America’s founding commitment to liberty as an unalienable right disappears and, as one of Vermeule’s followers, Josh Hammer, put it, citizens’ own perceptions of what is good for them become “constitutionally irrelevant.”

The third principal stream feeding the New Right is National Conservatism, sparked by Yoram Hazony’s The Virtue of Nationalism. Hazony argues for the nation as the best form of political community and sees a world of independent nation-states as superior to internationalism and imperialism, terms he deploys so broadly as to include the European Union. He embraces John Stuart Mill’s vision of independent nations as the best protection for pluralism among ways of life and endorses history and tradition as legitimate bases of national particularism.

But as Field notes, Hazony believes in pluralism between nations, not within them. Religious and ethnic majorities, he argued, are entitled to play dominant roles in their society. Tacitly rejecting the U.S. Constitution’s prohibition of a national religious establishment, he argues that the religion of the majority should be the religion of the country, with limited accommodations for religious minorities, a proposition that becomes part of National Conservatism’s “Statement of Principles.”

National Conservatism’s embrace of history and tradition as the sources of national particularity goes hand in hand with Hazony’s rejection of universalism as a mode of thought, and it leads to a striking result—the rejection of the “creedal” account of the United States. Lincoln famously insisted that the American nation was dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal, that this dedication constitutes the core of America’s identity, and that American history is best understood as the always incomplete effort to live up to the nation’s founding creed. It is no accident that one of National Conservatism’s intellectual leaders, Chris DeMuth, the former president of the American Enterprise Institute, has been moved to deny outright the creedal account of America—or that one of its most important political acolytes, Vice President JD Vance, recently has done the same when he noted that “heritage Americans” whose ancestry goes back to the Civil War have “a lot more claim” over the country.

Outside this triad of contributors to the rise of the New Right lies what Field terms its hard underbelly—a rogues’ gallery of monarchists, fascists, eugenicists, and male supremacists. The details, fascinating but horrifying, are beyond the scope of this review. What matters, Field shows, is the New Right’s inability, and in some cases unwillingness, to police the boundary that demarcates acceptable iconoclasm from outright bigotry. The reaction of the Heritage Foundation to Tucker Carlson’s interview of a notorious antisemite, which occurred after Field’s book was published, perfectly illustrates her point.

With the exception of foundational religious texts for faithful believers, no book is perfect, so I conclude this review by doing my reviewer’s duty to find fault. I will mention two.

To begin, having studied as a young man with Strauss and several of his oldest students, I have firsthand knowledge of many of the Straussian dramatis personae, and I cannot escape the impression that in her effort to extricate herself from this world, Field was unfair to some of its members. For example, while I agree with Field that Mansfield’s book on manliness was substantively misguided and contributed to the New Right’s misogyny, his work on executive power, the most urgent political and constitutional issue of our time, is groundbreaking and worthy of serious study by liberals. The work of many other Straussian scholars—Walter Berns, Herbert Storing, Robert Goldwin, and the husband-wife Zuckert duo, Catherine and Michael, for example—has illuminated the origins and development of American political institutions. Although the Claremont Institute has contributed its share to the excesses of the New Right, its intellectual inspiration—Harry V. Jaffa—wrote (as Field rightly acknowledges) one of the very best books on Abraham Lincoln’s significance for the American political order. It would be unfortunate if Field’s focus on the excesses and mistakes of some in the Straussian world led future students to shun it.

Second: in the introduction to her book, Field rightly cautions readers not to dismiss New Right thinkers as “dumb fascists.” Many of them are smart, highly educated, and well informed. “To believe that there is nothing to learn from these thinkers and no compelling noneconomic reasons to support something like Trump ... is naïve and dangerous,” she insists. “Growing right-wing extremism has not emerged in a vacuum,” she adds, but in many respects represents “a response, however misguided, to real problems, and to the real vulnerabilities of liberal democracy.” Although she briefly returns to this theme in the conclusion, she only partly redeems the promissory note she issues. This reader does not come away with a clear sense of her take on why the New Right eruption occurred when it did and took the form that it did.

Field’s book is long and ambitious, and perhaps it is unfair to suggest that it should have been even longer and more ambitious. So I’ll leave it at this: when this book goes into a second edition, as I suspect it will, she should undertake an epilogue that moves from the What of the New Right to its Why. In the meantime, readers will benefit from the best researched and most comprehensive account of the New Right that has appeared—or is likely to.

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

This was a good review. Thank you. I’m going to pick it up based on your recommendation.

I'm of the same generation as Mr. Galston but have watched the developments of the conservative / right-wing / MAGA movements of the past decades from far outside those orbits. Although I'm familiar with most of the figures and ideas Galston highlights in Field's book, I'm more used to narratives that make Buckley / Reagan / Buchanan the storyline (and the "underbelly" tradition of the "intellectual dark web"). Galston's review seems to me in itself so interesting and analytically clear that I plan to get Fields' book and bring order to my understanding of the different stream of storyline she articulates.

Thanks to Mr. Galston for an very informative and engaging review, and to the UnPopulist for publishing it.