Political Triumphalism Is Contrary to the Spirit of Yom Kippur

The Jewish holiday’s emphasis on repentance requires confronting our past sins, not burying them

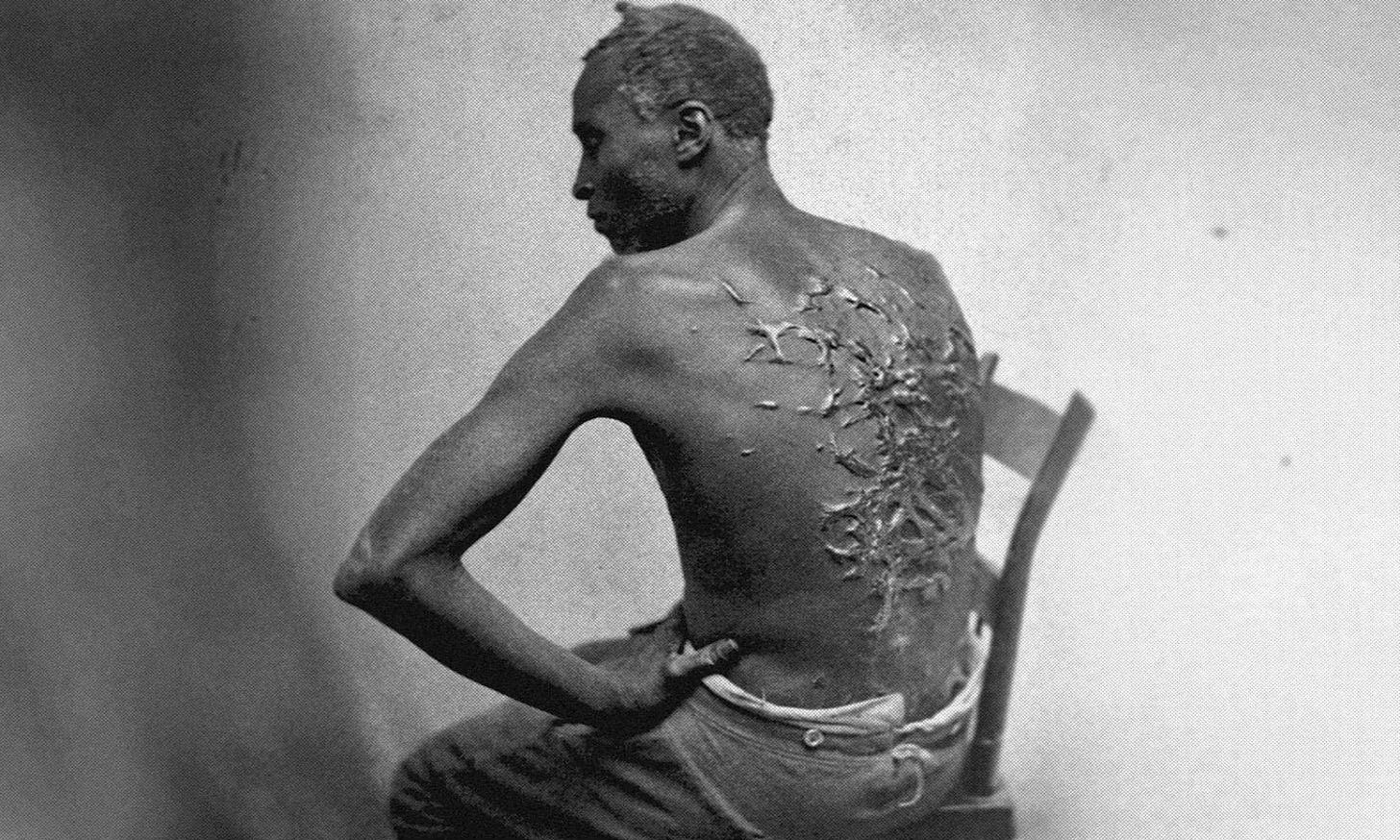

I can only imagine the scene that day in March of 1863 when Peter wandered into a Union army camp in Mississippi. Ten days earlier, he had escaped from slavery, along with three others, still bloodied from a recent brutal whipping. Peter and his companions had rubbed onions all over their bodies to hide their scent from the dogs they knew would follow. They swam across creeks and hid in the mud. One was caught. When the three remaining runaways finally staggered into the camp, they were overjoyed to see Black soldiers in Union blues, and they immediately enlisted to fight.

Before they could receive their uniforms, they had to see the camp doctor. When Peter took off the rags that passed as clothing, the white soldiers stared in shock. Beneath the more recent wounds, they saw layer upon layer of keloid scars crisscrossing his back from his pelvis to his neck.

Two itinerant photographers happened to be at the camp that day. They captured an image of Peter’s back and then reproduced it as a carte de visite, which was a new type of media, a piece of cardboard a little smaller than a 3x5 card today, imprinted with a photograph, and sold individually around the country. The picture of Peter went everywhere, and when it was reprinted in Harper’s Weekly it received the title, “The Scourged Back.” It showed the country the brutal and ugly truth of slavery with a vividness some had never seen before. Scholars believe it came at a critical time, when support for the war was faltering, and it galvanized the North to fight on for two more grinding, bloody years.

Scourged Back to George Floyd

Given how many photographs we all see in a day, none of us can fathom the power of the carte de visite for first timers. It was passed between people in a way that led to a kind of communal witness—the image was not just an image, but a social experience. The closest comparison for us might be what happened in the summer of 2020 when the video of George Floyd’s murder circulated online at a time when we were all home during the pandemic. It was as if we all watched it together in those weeks of late May through early June five years ago. And, like the carte de visite, it galvanized us. Even in sleepy suburbs, America came out into the streets. Just as in 1863, we thought we could see America clearly during those days. We came together and said, “We can do better than this.”

The problem, of course, is what followed. In 1863, the choice was clearer because the nation was already at war. But in 2020, that post-George Floyd moment splintered into a thousand different interpretations of the video. Slogans and agendas proliferated, each of them pointing in a different direction. These were all attempts to address the same deep and violent American urges evidenced in those scars on Peter’s back. The problem was how they all claimed competing monopolies on truth.

So when the pandemic moment passed and the world shifted back to work in 2021, objections to these campaigns gained momentum as the social experience created by the video receded. Many a pundit gained notice—and wealth—complaining about overreach of DEI programs, and soon their voices were much louder than the serious people making a good-faith effort to address police reform. Today, theories abound that Floyd’s death resulted from other health problems, not officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on his neck for over nine minutes while he lay helpless on the ground, or that Chauvin’s subsequent conviction was politically-motivated injustice. Any consensus on truth was gone.

I share this story because it illustrates the social problem of truth—a problem we cannot avoid if we are to take the idea of teshuvah, or repentance, the core purpose of this day, seriously. Maimonides teaches that teshuvah begins with the recognition of the sin, the agreement that the act indeed was done and that it was either a mistake or simply wrong. Only with that fact established can a person proceed to the next steps: the confession of the mistake, the verbal apology and attempt at repair, and the commitment not to err again in the future. The process is a way to say with honesty and conviction, “I am better than this,” or to say together, “We can do better than this.” But teshuvah begins with seeing the truth of the event itself.

All of us share an amazing capacity for rationalization and even self-delusion—cognitive distortions that cause us to misremember the past. We can get stuck in harmful patterns of behavior and refuse even to see the actions contributing to the pattern. Sadly, we often need a major crisis to see that which led to the sin in the first place.

And all of this is true for individual sins, the mistakes we make on our own. It is doubly true for social sins that we commit collectively. Think about the last time you got in an argument with someone you love and couldn’t agree on who did what, to whom, and when. Think about how much you dug in on your version of the truth the more you felt defensive and under attack. We all know this frustration, and the landmines it causes in every relationship. Now magnify that problem across a family—unrecognized harms and unspoken sins turn into generational trauma. Now magnify it across a society—the unseen, unacknowledged, unaccepted wrongs of the past spread among the people, like a stubborn smog, seeping into local communities. Now magnify it across a country the size of a continent, and it becomes a part of the national subconsciousness, a hushed element lying beneath our collective memory. To appropriately turn away from an individual sin does not require ongoing remembrance or memorialization—but a collective, national sin of the magnitude of American chattel slavery does, because its effects and lessons remain with us.

Sadly, the way that many respond to this problem at the social level is with power. The party with more power just steamrolls any dissent and insists on a monopoly on truth. This is the easiest way to avoid a real search for what is true.

The Public Erasure of Sinful History

This is why you will not see the image, “The Scourged Back,” hanging in any National Park or Historic Site anytime soon. The Department of the Interior instructed parks to take it down in compliance with a March executive order from the president that banned images that spread “corrosive ideology” that “disparages historic Americans.” It does not issue an instruction to contextualize the images—as it might if the Trump administration believed the past is worth acknowledging but alongside a presentation of the gains we’ve made since then—it outright bans them.

So the historic photograph has come down along with, evidently, any references to slavery at Harper’s Ferry where abolitionist John Brown led a revolt or mention of George Washington’s slaves at the President’s House site in Philadelphia. The very places created by our government to provide social experiences of truth, the places where Americans can stand in the same room, see “The Scourged Back,” and decide for themselves what it said about America then, and what it means for America today, have become hollow shells of their former selves.

On the surface, the “corrosive ideology” in question refers to all those slogans and acronyms—e.g., “Defund the Police”—that proliferated after the summer of 2020. That is not how the administration is proceeding. Instead, it is using that directive to shutter and close significant aspects of our national history—as if displaying the basic facts of America’s past is somehow the same as recommending a faulty DEI program. But I am a rabbi, and so beneath every surface meaning I seek a deeper message, a midrash indicating the moral question at issue.

Ultimately, what Trump’s executive order considers corrosive is repentance. The “corrosive ideology” in question is the idea that the public should reflect on anything our country might ever have done wrong. And the wrongs in question, systematic mistreatment and subjugation of a people group, are not wrongs that are causally inconsequential in our own day; these are wrongs whose reverberations are still felt today. The executive order holds that a harsh moral judgment of our nation’s past behavior is disparagement, and, by implication, that any effort at teshuvah is impossible.

The goal is to weave what I recently heard Anne Snyder call “a malignant narcissism” into the very fabric of the nation. The agenda is not just political but also theological—it flows from a theology that says all sins are private and can be absolved by loyalty and faith in a messianic leader. It is much older than Trump or MAGA, as it emerged out of the seeker-sensitive Christianity of the 1980s that intentionally removed the public confessional prayers from Christian worship. Today, there are 6,000 megachurches across America, each attracting thousands or tens of thousands of worshippers every Sunday, each providing the spiritual release of forgiveness without personal public acknowledgement of any particular sin. That is the theology that sees the search for socially-actionable truth as a “corrosive ideology.”

Eliminating the Social Space for Teshuvah

Last week, on Rosh Hashanah, I preached two sermons about the need for covenantal communities to help us find a way out of the technologically enforced despair and powerlessness of postmodern life. Those communities protect the virtues of grace and compassion as we search for truth; they allow people with different understandings of the past to show chesed v’emet—love and truth together. We are not supposed to put all of our problems into the political sphere, but instead to have places, spaces, institutions, and leaders which help us contemplate, deliberate, reflect, and identify the obligations we find when we encounter truth.

With his actions, President Trump is hollowing out some of those spaces. The damage he does is not only that he hides the sins of the past from public view, but even more pernicious is the message that as a society we cannot handle seeing those sins. If the carte de visite once created a social experience of truth, the executive order seeks to prevent it. It says that our attempt at teshuvah is “corrosive.”

To that I repeat the words said by generations of Americans before me, the words said by pastors and rabbis, presidents and governors, doctors and truckers, men, women, children, citizens and residents, wood choppers and water carriers, over and over throughout our national history: “We can do better than this.”

Even if all the programs and agendas that came out of the George Floyd moment were insufficient or faulty, the solution is not to give up and deny the possibility of teshuvah, to live in a world without public confession, to use the word “woke” as a get-out-of-responsibility card. The solution is to find a different way.

You do not need me to tell you that we are living in a political, social, and cultural crisis. I have been saying that for years. Now, I add to that list that we are living in a theological crisis. The MAGA movement seeks to promulgate a triumphalist theology that attempts to determine the truth of America’s past and says that repentance is impossible because doing so would be “corrosive” or “disparaging.” This theology is built on the fundamentalist, extreme myth that it has the absolute truth of who we are as a Christian nation, and thus the only acceptable response is obedience.

Remembering Our Sins Is Necessary for Teshuvah

Yom Kippur is the antidote to this theology. It is the Jewish insistence that all of us are seekers of an asymptotic truth, that we are equal in that search and owe each other grace and compassion along the way. Our theology says that the gates of repentance are always open, that teshuvah is possible, that it starts with working together to see the truth, to recognize its errors, to attempt repair, and to commit to a better future.

Our theology beckons us to inhabit places that seek truth through the virtues of grace and compassion. If the Trump administration succeeds in gutting our museums and parks, if they succeed in eroding the possibility that universities remain havens of free inquiry, if they succeed in eroding the rule of law and judicial procedure, if they tear down every place in America where truth is a virtue pursued by communities of dignity and respect with grace and compassion, then we must be the places that continue to insist, “We can do better than this.”

From this day forward, everyone who walks in the upper lobby of our building will encounter a poster which has two photographs and the following caption:

The photo on the left, known as “The Scourged Back,” displays the horror of America’s greatest sin, slavery. The photo on the right shows an example of America’s highest potential, Martin Luther King Jr., Abraham Joshua Heschel, and other religions leaders marching for fair voting rights at Selma.

I will be honest. I would prefer that the work of seeing the truth of American history remain in the institutions set up by our government for that purpose. However, when the president of the United States implies that the possibility of teshuvah is a corrosive ideology, then we have no choice but to use the blessings of our institutional independence and our religious freedom to protect truth as a core value of our civic life.

Right now it is “The Scourged Back”—pretty soon it will be pictures of Jews hanging off the rails of the St. Louis as they were denied refuge on American shores.* Part of me wants to say this is like the moment in Pastor Martin Neimoller’s famous poem, “First They Came”—and that may be true.

But on this night, even more disturbing to me than the attack on the teaching of racism and slavery, even more disturbing than the possibility that the next attack will likely be on teaching the history of antisemitism, is the attack on truth itself. Repentance starts with seeing the truth.

We can do better than this.

* We claimed that a directive by the administration had led to the Holocaust Memorial Museum temporarily closing its exhibit, “Americans and the Holocaust,” but a fuller description should have noted that the exhibit was also due mechanical upgrades that were planned prior to Trump retaking office. The omission is regretted.

This essay is adapted from Rabbi Michael G. Holzman’s Yom Kippur sermon delivered at the Northern Virginia Hebrew Congregation on the evening of Wednesday, Oct. 1, 2025.

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

More than just “whataboutism”, the “But, Gaza” and “ripe for including Gaza” comments play into the one side of the dual-loyalty coin - that Jews are more loyal to Israel than their own countries. The flip side of that coin is that Jews everywhere (in this case an American rabbi) must answer for the sins of the Israeli state. While likely not your intention, that’s a fair interpretation of your comments in the context of the rabbi’s article. Also, given the occurrence of Yom Kippur last week, the rabbi was using teshuvah to illuminate how a fundamentalist theology is being used to undermine the concept of repentance - in our country right now. He was not suggesting that there aren’t other situations in the public sphere to which repentance also might apply.

Important teshuvah moment: an alert reader informed me (offline and very politely) that the Holocaust Museum exhibit referenced at the end of the piece, was scheduled for renovation (HVAC repair and the like) long before President Trump began his second term. I should ahve probed further when I heard the exhibit was closed over Labor Day. The administration's desire to whitewash the unpleasant parts of our national history is so well known, it was plausable (but not factual) of me to assume this exhibit's content would be modified. Given that the sermon is about the importance of truth, I think this correction is key. Besides, there are so many other examples of the President erasing hard truths about America's past, that this case turned out to be innocent does not undermine the point of the sermon.

Meanwhile, the administration did, in fact, fire all 12 people appointed to the Holocaust Museum Council by the Biden administration, including former 2nd Gentleman Doug Emhoff. The Council has a long history of appointments from Presidents of both parties, but never a wholesale firing of a prior President's picks. I hope the content of its exhibits continue to be immune from politicization.