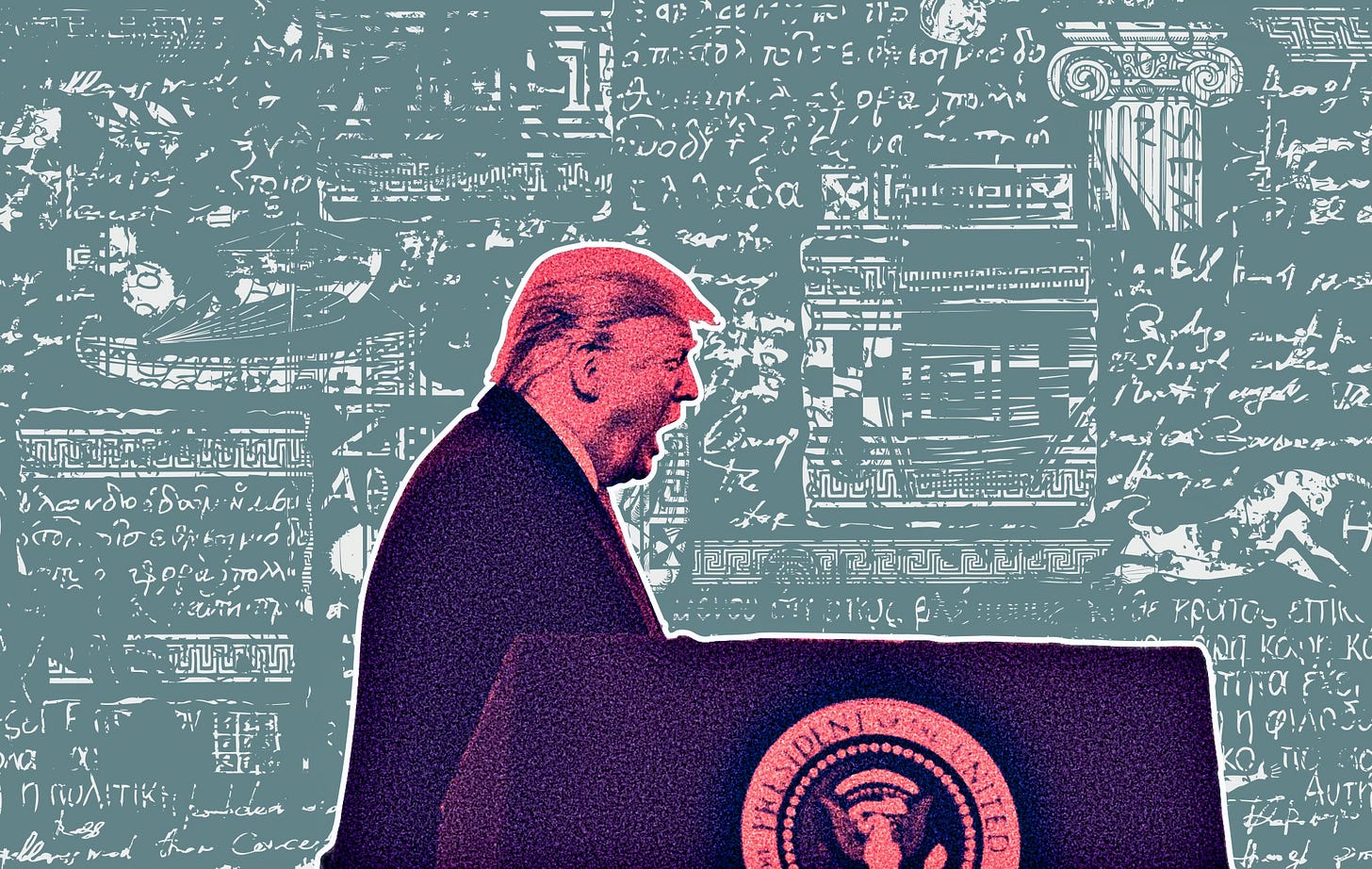

From Athens to Sparta: How Trumpism Is Driving America’s Decline

Civilizations commit suicide when they build walls against the outside world

How do you create a golden age? In my book Peak Human, I tried to answer that question by examining seven exceptionally creative and innovative civilizations—ancient Athens, Rome, the Abbasid Caliphate, Song China, Renaissance Italy, the Dutch Republic, and today’s Anglosphere.

Apparently, it is not geography, since the center of progress keeps shifting around the globe. Nor is it religion. The cultures I studied were pagan, Muslim, Confucian, Catholic, Calvinist, Anglican, and secular. What set them apart was not what they believed, but how they believed it—not as rigid orthodoxy, but in ways that allowed them to remain open to discovery and innovation.

The ancient Greek historian Thucydides observed that there are two opposing human mentalities: the Athenian, always innovating, always venturing out to learn and acquire something new; and the Spartan, staying put in order to defend what he already has.

All golden ages were Athenian in this sense. They tended to emerge at the crossroads of civilizations, learning from migrants, merchants, and missionaries who crossed their borders. They were maritime traders, bringing home not only valuable goods but new ideas. By remaining open, they could draw on more minds and more creativity than closed societies ever could. They often sustained systems of alliances that preserved peace and protected trade routes.

They also enjoyed more freedom at home, relatively speaking, though of course not for everyone. As the classicist Mary Beard has noted, when people say they admire ancient Rome, they imagine themselves as emperors or senators—a few hundred people—never as the enslaved masses in mines, plantations, and households. Women had few, if any, rights in these civilizations.

But that was not what their neighbors noticed. Slavery and oppression? They had that at home, too. What struck outsiders about Rome, Abbasid Baghdad, or Song China was the extent of freedom enjoyed by relatively large segments of the population compared to their own, and the correspondingly higher living standards.

The economic historian and 2025 Nobel laureate Joel Mokyr has pointed out that every act of innovation is “an act of rebellion against conventional wisdom and vested interests.” The corollary is that wherever conventional wisdom and vested interests enjoy veto power, very little happens. Churches, monopolies, guilds, and aristocrats blocked ideas, technologies, and business models that threatened their power or wealth. Sustained innovation appeared only where more people enjoyed individual freedom and property rights, and where force was restrained by some form of rule of law and divided power.

Turning Gold to Dust

This also helps explain how golden ages ended. Somehow, they lost that openness and freedom. As the historian D. C. Somervell remarked (summarizing a point by Arnold J. Toynbee), societies don’t die from natural causes, but from suicide or murder—and “nearly always from suicide.”

These cultures faced many crises—war, plague, famine—over their long lives, yet they often bounced back from them. Invaders could be repelled or absorbed, and cities could be rebuilt. What truly ended golden ages was something else: Under threat, societies tend to seek stability and predictability, attacking what is different and unpredictable.

There is a kind of social fight-or-flight reflex, driving us to hunt for scapegoats and retreat behind physical and intellectual walls, even when complex dangers call for learning and creativity rather than mere avoidance or aggression. In short, we turn from being Athenian to being Spartan.

Even Athens itself became more Spartan during the long and brutal Peloponnesian War at the end of the 5th century B.C. “There was a general deterioration of character throughout the Greek world,” Thucydides wrote. “What used to be described as a thoughtless act of aggression was now regarded as courage. … Any idea of moderation was just an attempt to disguise one’s unmanly character; ability to understand a question from all sides meant that one was totally unfitted for action. Fanatical enthusiasm was the mark of a real man.” (Sound familiar?)

Shaken by war and coups, Athens—the birthplace of democracy and free speech—even sentenced its greatest philosopher, Socrates, to death in 399 B.C. All golden ages experienced some kind of death-to-Socrates moment, when curiosity was replaced by control and dissidents, Jews, or migrants were turned into scapegoats.

In the crisis-ridden late Roman Empire, pagans persecuted Christians, and then Christians persecuted pagans. When the Abbasid Empire faced religious competition, the caliphs forged an oppressive alliance between state and religion. The Renaissance ended when embattled Protestants and Counter-Reformation Catholics built their own state–church alliances to persecute dissenters and scientists. Even the tolerant Dutch Republic fell to Calvinist zealots during destructive invasions of the 1670s and purged its universities of Enlightenment thinkers.

In turbulent times, societies often call for strongmen, and rulers centralize power, undermining commerce and the rule of law. Late Roman emperors grew ever more authoritarian; Abbasid strongmen tightened control over both markets and minds; late Renaissance rulers used cannons to demolish city walls and republican institutions alike.

This turn toward orthodoxy and centralization makes catastrophe self-fulfilling. By limiting access to alternatives, it restricts the adaptation and innovation that could have helped societies cope with danger. After the upheavals that ended Song China, the Ming dynasty centralized the economy and banned foreign trade altogether. They achieved stability—through 500 years of stagnation.

Hard times create strongmen, and strongmen create even harder times.

“History is a vast early warning system”, said Norman Cousins. What is it warning us about today? The answer seems painfully obvious. A succession of crises—financial crashes, wars and geopolitical rivalry, migration flows, a pandemic —has replaced the confident, exploratory mindset with a sense that the world is dangerous and must be shut out. In just a few years, we seem to have gone from being Athenians to being Spartans.

America’s Backward Turn

In the United States, it is hard to escape the feeling that President Trump has read my book in reverse. He speaks of unleashing a new American golden age, but the way in which he is upending many of America’s greatest strengths seems designed to move the country straight toward its phase of decline and fall.

The attack on trade and immigration is meant to make America less open to outside ideas and innovations. MAGA has one-upped the illiberal campus left’s tactics of imposing an orthodoxy on American universities—not by disinviting speakers and storming stages, but through government threats. Efforts to overwhelm the judiciary, intimidate media and law firms, and control the Fed confirm an ambition to dismantle independent institutions and checks on executive power. When the administration forces business leaders into silence—or into offering Trump gold-plated tributes—in exchange for favors, this is not just corruption; it is an attempt to subordinate society itself.

This is a dangerous moment for America—but also for the world. After World War II, the United States built a rules-based international order that was far from perfect but at least rested on open seas, international law, and negotiation rather than gunboat diplomacy—and for a time, it truly made the world safe for democracy.

Now that Trump threatens not only dictators but also allies like Mexico, Canada, and even Denmark with military force, that order is coming apart. Former allies will see themselves forced to try to appease tyrants in their regions, or rapidly rearm—even with nuclear weapons.

One is reminded of Athens’s brutal treatment of its own Delian League, an alliance of Greek city-states to protect each other from Persian aggression, the ancient version of NATO. It began as an alliance for mutual defense and to keep trade routes open, but eventually, as war eroded character, Athens fell for the temptation to use its military superiority to extort allies and even attack them to steal their resources.

In 416 B.C., the Athenian emissary to neutral Melos delivered a line, recorded by Thucydides, that could have come straight from the new MAGA national security strategy: “The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

Someone should remind Trump that this was not the beginning of Athenian greatness, but the beginning of its end. By abandoning its reputation for reliability and loyalty to its friends, Athens drove its former allies to seek new protectors and eventually to conspire against it.

Picking Up America’s Mantle

The decisive question today is whether the American-led world order can survive without America—carried forward by the many countries that grew rich and democratic within it, from Europe, Canada, and Australia to Japan, South Korea, and the Latin American democracies.

If they manage to uphold rules and deepen trade together, the present global golden age might yet be transplanted into a more decentralized world—just as the British inherited it from the Dutch, and the Americans from the British. With some luck, the United States might then suffer a bout of FOMO and return.

Whether Europe has the will remains unclear. That the E.U. found it so difficult to conclude a Mercosur trade agreement after 25 years of negotiations (France voted against it and the European Parliament has delayed ratification) suggests that it cannot yet choose between saving its beef lobby or the world order.

But if others do succeed, America may find itself in the odd position of repaying a compliment once paid by Britain, when it lost its American colonies, and Alfred Tennyson wrote:

Strong mother of a Lion-line,

Be proud of those strong sons of thine

Who wrench’d their rights from thee!

Just as Tennyson saw the United States as the truest heir of Britain’s own ideals, so today it is fair to say that the countries defending free trade and the rule of law are preserving the American world order from an America that has—250 years after its founding—let’s hope only temporarily forgotten what it stood for.

They have, as Tennyson wrote, merely “Retaught the lesson thou hadst taught.”

© The UnPopulist, 2026

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

I haven't had a chance to read your book Peak Human yet, but this makes a lot of sense. When you close borders and limit trade, you're depriving the world of ideas, innovation and progress. Remember Carl Sagan's reflection at the end of Cosmos. He poop pointed out that the Mediterranean Sea made it easy to escape the tyrants and keep trading goods and ideas.

Valuable observations. Interestingly, Plato/Socrates thought that the solution of Athenian problems was a sort of ideal state that without social mobility and that would be isolated, located away from the sea and protected against the poisonous influence of the outside world...