Can Each Side's Faith Break the Cycle of Mutually Assured Destruction for Israelis and Palestinians?

An epistolary exchange between an Islamic scholar and a rabbi points to the concept of universal empathy in their traditions as the key

Dear Readers:

Two months ago, the Institute for the Study of Modern Authoritarianism held its second annual “Liberalism for the 21st Century” conference (LibCon2025). The conference assembled liberal thinkers, journalists, activists, and concerned citizens of diverse nationalities, faiths, and sexual orientations to develop a renewed defense of liberal values at a time when these values are under attack from illiberal ideologies and authoritarian forces. A chief aim of the convening was to spark conversations and build bridges across policy and identity divides among liberals of various stripes.

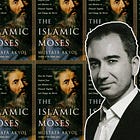

For that reason, we are delighted to publish—on the second anniversary of Hamas’ brutal attack on Israel—an exchange between Rabbi Michael G. Holzman and Cato Senior Fellow Mustafa Akyol, a practicing Muslim and scholar of Islam who immigrated to the U.S. from Turkey. Their conversation began when they saw each other at LibCon2025 and expressed their distress about the deteriorating relations between their two communities since that horrific day and the devastating war in Gaza that followed. They continued their correspondence over email in subsequent weeks.

With mutual respect, they convey to each other the terrible pain that their communities are experiencing while drawing from their own respective faiths to emphasize the vital need for empathy to overcome the logic of mutually assured destruction that the two sides are locked in. This logic, they note, is taking not only a physical but also a spiritual toll on both communities.

Both are valued contributors to The UnPopulist, and their joint commitment to liberal principles enabled this productive dialogue—one that models how people of goodwill can bridge deep divides. We hope you’ll find it as valuable as we do.

You can access the LibCon archive here, and our ongoing Liberalism & Religion series, which explores the liberal ethos in every major faith tradition, here.

Berny Belvedere

Senior Editor

Dear Mustafa:

I was so grateful to run into you last week at LibCon2025, because it has been over nine months since we last spoke about the need for greater Muslim/Jewish dialogue in America. At that point, Oct. 7 and the horrendous warfare in Israel/Palestine was just over a year old. Now we approach two years, and in that time the strong bonds between Muslim and Jewish institutions and leaders in America have entered the Ice Age. Previously warm relations have frozen over into tense silences or complete avoidance. This is bad on so many levels, and I hope that our chance meeting last week can help us find a way forward. Perhaps with the discipline of writing we can, through an email exchange, illuminate the obstacles our communities face and find ways to overcome them.

Before we get into the heart of the matter, I want to lay my cards on the table. I have three reasons for this work:

First, the estrangement between our communities is personally painful. As you may recall, my congregation has been in conversation with a large local masjid for over two decades. We host one of their satellite locations for Friday prayers every week, and during every night of Ramadan. After Oct. 7, I exchanged messages with their spiritual leader, Imam Mohamed Magid, recommitting to our relationship and addressing the reality that we have avoided open conversation about Israel/Palestine for way too long. I expressed that, after a reasonable amount of time to heal, we must correct that avoidance. I think that time is now.

Second, our estrangement is extremely bad for American democracy. Jews have long played the role of religious outsider for America. Muslims more recently stepped into that role as Jews became more accepted, and 9/11 acted as kerosene for Islamophobia. But American religious freedom depends upon openness, respect, trust, and a belief that universal human dignity includes diverse ways of faith. If we cannot speak honestly to each other, then how can we speak honestly in multi-faith environments in general? How can we model the moral bonds that hold a diverse citizenry in healthy tension if we choose silence over speech?

Third, our estrangement is extremely bad for Israelis and Palestinians living in the warzone right now. While a complete exploration of the connection between diaspora and indigenous communities is beyond the scope of this conversation, I have seen the ways that American Jews and Muslims model and inspire hope for those living in the Promised Land. The entire culture there is saturated with mistrust, cynicism, despair, and outright fear of “the other.” Given the safety, security, history, and civil structure we enjoy here in American democracy, we have an obligation to at least try to bring some of our light to the darkness over there.

I suppose I have a fourth reason: for too long, we have allowed the public discourse around Israel/Palestine to be dominated by extremists on both sides here in America. Both partisan Zionists and anti-Zionists have distorted perceptions of the reality of the conflict due, in large part, to political objectives over here. Enough!

So, we must do something. When I asked your thoughts on how to thaw the relationship, your immediate reaction was to say, “We must start with empathy.” I think that is right, but I want to hear more from you on that. So, why empathy?

L’shalom,

Michael

Dear Michael:

Thanks so much for reminding me of our recent conversation at LibCon2025, and for following up with these thoughtful observations. I, too, believe in the need for greater Muslim/Jewish dialogue in America—and even beyond. And I, too, painfully observe the extremely difficult moment in which we find ourselves.

It is extremely difficult, first and foremost, because we have been witnessing the intense suffering of people whom we feel deeply connected to. For many Jews, the latest and darkest chapter of this century-old tragedy began on Oct. 7, when a terrorist attack on Israel killed hundreds of innocent civilians and took many others as hostages. For many Muslims, it began soon after, when the Israeli response began to devastate the Gaza Strip, killing not just Hamas militants but also thousands of innocent civilians and causing the displacement, agony, and starvation of over two million people, half of them children. People on both sides have been painfully observing all this horror, often only focusing on their own side, and thinking, “This is what they are doing to us.” The result is entrenchment against “them,” denial of their suffering, and delegitimization of their story. It has even led some people—unbelievably—to declare that there are no innocents on the other side.

That is why I believe empathy at this moment is essential. That means seeing the other side not as evil enemies to be crushed, but fellow human beings caught on the opposite side of a tragic conflict. That means realizing that their own suffering is the main reason behind their stance against you. That means understanding that they have some hopeless fanatics on their side—but just as you have yours on your side. That also means deeply feeling that all children are equally innocent, and all their lives are equally sacred, whether they are from Kibbutz Be’eri or from Gaza.

Now, fanatics on both sides hate such empathy. They condemn it as weakness, if not treason. They see it as a hindrance to their war propaganda, and an obstacle to their ultimate victory. But we should all push back, because nothing good can come out of their militancy. Even if our side really wins the “ultimate victory,” it will leave us with a crushing moral burden that will haunt us for generations. We will realize that, without empathy, little has remained of our own humanity.

I hope this is a helpful start from my side, and I would love to hear your thoughts.

All best,

Mustafa

Dear Mustafa:

Thank you for your wise words. This is a helpful framing. We are talking about the tension between a universal belief in human dignity (which would inspire empathy for all people who are suffering), and the natural instinct to circle the wagons, fear the enemy, and restrict empathy to one’s own side. I am with you: all warfare is revolting, and the suffering of war should trigger empathy in all of us. However, as you accurately describe, Muslims and Jews are so deeply traumatized by the violence, suffering, devastation, and degradation we are seeing in Gaza, and by the barbarity we saw on 10/7 and still see in these cruel hostage videos, that we are pushed to limit our empathy only to our side.

Universal empathy competes, within each of us, with tribal empathy.

In the middle of ongoing warfare, a path forward is extremely difficult to find. Attempts to bring our communities to universal empathy, to the belief in the universal dignity of all humans, and especially to the unquestionable right of safety for children, is constantly countered by exposure to the other side’s acts of violence, or even their symbolic expressions of hatred. The extremists need only fire missiles, or shoot off hateful eliminationist words, and a universal empathy appears naïve, or at least a bridge too far. Exacerbating this problem, of course, is the algorithm’s power to amplify extremist action and words.

Making matters even worse is that anyone who preaches universal empathy, or any concern for the other side, faces immediate attack from the thought-police of their own tribe. Empathy for “the other” is seen as the betrayal of one’s own. Forgive me if I sound exhausted by all of this, but I cannot tell you how many efforts at dialogue have foundered upon the rocks of feared online annihilation. And I cannot tell you how fatigued I am by the constant policing of my own words, for fear of being misconstrued online and hurting someone in my community, someone who might be deeply afraid and suffering. Since all of this is happening amid a wider attack on liberalism’s bedrock of universal human dignity, empathy sometimes feels like a distant virtue at the peak of human morality as leaders who seek dialogue dangle over chasms of rage. I would much rather be up at the summit.

So I ask: How can we get there? What can we do to counter the extremists? Yes, I agree we defeat extremism by reminding ourselves of the suffering of “the other,” and by remembering that their anger emerges out of their pain. But what practical steps can we take to make this happen?

I am a congregational rabbi so I will start with one idea: we have to do this in person. We need to find ways to see other people face-to-face, ideally in a quiet, sacred space, maybe bracketed by words of prayer or lessons from our sacred texts. Empathy stands a chance when we see the slumping posture of grief in a conversation partner, as the words of the Shema or the Imam’s adhan still reverberate in the room. Human vulnerability does not come across well in words on a screen, or flat faces on Zoom. I would love to hear your thoughts on that. Is it pragmatic? Do our traditions have the words and the tools to make such an experience possible?

Thank you for thinking through this with me,

Michael

Dear Michael:

Thank you for putting it succinctly: We are indeed talking about the tension between a universal belief in human dignity, which instills empathy for “the other,” and the natural instinct to protect our own tribe, entrenching ourselves against “the other.”

To some extent, the latter instinct is understandable and even justified. In my neighborhood, I care about my own family first—the safety and well-being of my children—and there is nothing wrong with that. However, I would be in the wrong if a member of my family turned out to be a bully toward the neighbors, and I stood by him no matter what, justifying his aggression simply because he is one of my own.

A beautiful Quranic verse has always inspired me on this matter: “O you who believe, uphold justice and bear witness to God, even if it is against yourselves, your parents, or your kin” (4:135). It teaches us that there are values higher than “us”—and that prioritizing those values is what will ultimately help “us,” by making us better people. If we lose this ethical framework, and place loyalty to our tribe above universal values, we begin to move toward a very dark place.

I have observed this tendency in the various nationalisms that have ravaged the part of the world I come from: the lands of the former Ottoman Empire. In my native Turkey, it is still difficult to call for empathy for the hundreds of thousands of Armenian women and children who perished in the horrific tehcir, or “expulsion,” of 1915—the innocuous term Turks prefer to use, emphatically rejecting the G-word.

Among Serbian nationalists, there is often little empathy for the Muslims systematically murdered, tortured, and raped during their genocidal aggression against Bosnia between 1992 and 1995. Some even celebrate the atrocities, nauseatingly, seeming eager to repeat them.

This is the dark road that the late great Israeli philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz —referencing Austrian poet Franz Grillparzer— warned us about, as it goes “from humanism, via nationalism, to bestiality.” There are moments in history when such destructive nationalism erupts within our peoples, often in times of genuine fear and real insecurity. It is hard, indeed, to push back against it without becoming an outcast. But we must, I believe, for two reasons. First, even if our own tribe wins its nationalist war, it may lose so much of its soul that we end up ashamed of our “victory.” If tribalism is hardwired in us, so is conscience or morality, which would ultimately haunt us.

The second reason is perhaps the more practical—and effective—one: the victory we seek may be an illusion, for there is no end to wars that leave no room for peace. No people has ever found solace in endless war; no Sparta has ever found happiness.

As for your idea of having to do this in person: Amen! I would love to do that whenever we can arrange it. And a sacred space would be even better. In fact, your sacred space is sacred to me, too—as synagogues are honored in the Quran, along with mosques, as holy places “where God’s name is much invoked” (22:40). In His name, we can try to understand each other better, and even to imagine peace together.

Mustafa

Dear Mustafa:

The Quranic verse you cite is precisely what we need, a commitment by each side to remain true to their understanding of God’s word, a commitment to bear witness, despite intraparty political pressure to attack the other side. This commitment likely must be publicly stated, especially because it is the intraparty extremists who pull the reality and perception away from supporting efforts at interparty empathy.

An amazing example is a key text from Talmud (Sanhedrin 37a), one affirmed by the Quran, which asserts that, “To save a life is to save the entire universe.” Yet the manuscript history shows that even this pillar of universal empathy has suffered efforts to limit the lifesaving power of this dictum only to Jews. In my pastoral role, I can honor those who are hurting by presenting the natural human instinct to limit empathy, and then in a more prophetic role I must also “bear witness” and challenge my side to seek interparty empathy.

While the new Trump ceasefire and “day-after” proposal is moving forward, it is riddled with opportunities for backsliding. Empathy will be essential to its survival, yet the virtue remains fragile. Our exchange gives me a glimmer of hope. Now we must turn this exchange into reality.

Michael

Dear Michael:

Thank you for reminding us of that fascinating parallel between the Talmud and the Quran (the latter in verse 5:32) on the preciousness of every single life. Meanwhile, your regret about the tribalism you have observed in your tradition, which has narrowed down the humanistic themes in our scriptures just to “us,” reminds me of similar problems in my own tradition.

Let us hope and pray that the ceasefire can really work and put an end to this nightmare that we have been painfully watching for two years. Even then, the memory of victims will surely haunt us forever, and recovery will be very hard—especially in Gaza, where the devastation seems apocalyptic.

Still, let’s hope for a better future, where the same cycle of violence does not keep returning, getting worse each time. Strategically, the only good solution is a political solution, as sober minds on both sides have long argued. Yet there is a deeper level, the human level, where we need to soothe anxieties, cure hatreds, and curb militancies. It should start with empathy, as you and I both intuitively felt in our first conversation back in August. It surely is a huge task that goes beyond any of us, but each of us can try to make a difference.

Personally, I have told my co-religionists for years that Jews and Muslims are not enemies, as some believe, that we only have a modern political conflict to resolve, and a much deeper “Judeo-Islamic tradition” to revive. I only hope to double-down those efforts. Meanwhile, I agree that we need to repair the ruined bridges between our communities, by talking to each other, once again, with empathy and respect. And I would be honored to take some steps together.

Mustafa

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

This felt like an important exchange that needs to be urgently amplified. Let us hold on to the hope of any and every kind, and whatever, whichever way this could be effectively addressed in immediately bringing the conflict to an end.

Religion kills. I did NOT say genuine spirituality, so no, the problems will not be solved