Trump's Iran Strike Shows the Urgent Need for Congress to Claw Back its War Powers

The president's unprovoked, unilateral attack builds on the terrible and unconstitutional precedent set by his predecessors

President Trump last night unilaterally decided to bring the United States into an ongoing war with a country of more than 90 million people. The last American wars in the Middle East and Central Asia spiraled into decades of unintended consequences and destabilization beyond anything the Bush administration anticipated at the time. And yet here we are, as a nation—we are going to war with a country twice the size of Iraq. And the president made this decision alone.

This situation is far from what the Founders intended.

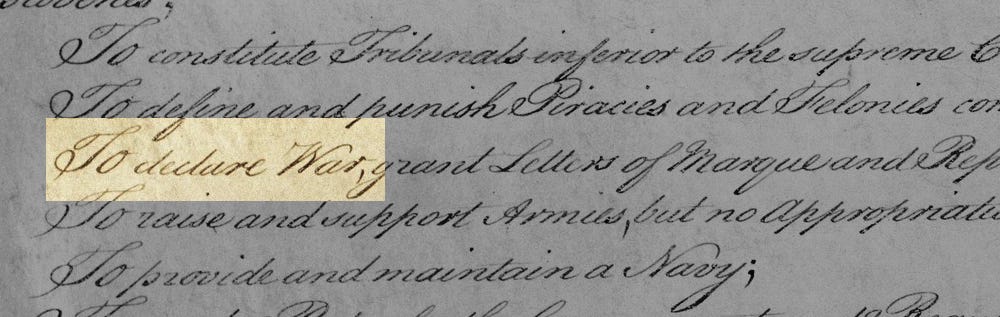

It’s right there in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution: “[The Congress shall have Power] ... To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water.”

Now, practically speaking, Congress has not officially declared war with anyone since 1942—though it has used the lesser tool of statutory force authorizations, which served as the legal basis for U.S. military action in both Iraq wars and the war in Afghanistan.

There’s a long and complex legal debate over the scope of presidential and congressional war powers that is far too extensive to get into here. But the exact scope is also not really the point. What matters is that war powers were supposed to be a shared responsibility between the president and Congress.

As my colleagues, Ian Bassin and Aisha Woodward, wrote last year in Lawfare:

Our Constitution divides the power of making war between Congress and the executive as an important check on that weighty responsibility. The executive has the ability to move expeditiously and can centralize the kind of decision-making in execution that a commander in chief needs to be effective. Congress, on the other hand, is more representative of public sentiment and its role ensures a democratic check so that any time the nation bears the costs of making war, it has the necessary public support behind it to prevail. To implement that division, Article I gives Congress the exclusive power to declare war and fund military activities, and Article II gives the president the power to manage foreign policy and command our forces.

In other words, the tension that emerges from trying to strike the right balance between deliberation and deliberateness—accountability and action—is how our system is supposed to work. War powers are designed to be a back and forth between the president and Congress.

This balance was, on the Founders’ part, quite intentional. The Constitutional Convention’s debates over exactly how to assign war powers are both fascinating and well-documented. And yet, in recent decades, we’ve slowly but decisively lost this balance. Despite the efforts of some in Congress, the decision of when to use military force—and potentially take the nation to war—is viewed as almost exclusively a presidential function. Now Congress offers very few (if any) practical checks on the president when it comes to moments like these. (For more on the long erosion of congressional oversight, see here.)

The lack of congressional involvement in decisions over whether to go to war is dangerous for two reasons.

First, there’s the narrow risk of bad decision-making. Weighty decisions should be deliberated carefully, with open and public debate over costs and benefits. This is precisely the sort of reasoned and careful deliberation that a legislature is supposed to undertake.

Without public debate, there’s a high likelihood that the White House will stumble into situations rife with unintended consequences. Vietnam is the classic example, where multiple presidents made a series of dangerously unaccountable and ill-examined decisions. Bassin and Woodward again:

The results were disastrous. More than 58,000 Americans were killed in Vietnam and the nation was nearly torn to pieces over it, with massive protests on the homefront, often directed at the very soldiers who were drafted against their will to fight a war that did not have sufficient public support. And just as the Founders feared, a war without public support was a war the U.S. was destined to, and indeed did, lose.

There’s no guarantee, of course, that greater deliberation and congressional oversight would have prevented disasters in Vietnam—or Iraq or Afghanistan for that matter—but it likely would not have hurt.

The second, even more insidious risk than poor decisions, is that an autocratic president could use his or her power to start a war not because it’s in the country’s best national security interest, but as a ploy to consolidate power at home. To be clear, I don’t really think we’ve yet reached this point in the United States even with Trump joining the war with Iran.

Still, there are various examples throughout history, from Putin’s invasion of Ukraine to the Argentine junta’s decision to invade the Falkland Islands in 1982, where unilateral military actions by authoritarian leaders were closely tied to efforts to shore up and consolidate power at home.

Put simply, the ability to single-handedly (and with no oversight) start a war is a massive amount of power. That power could easily be abused in ways that are foreseeable and unforeseeable alike.

It is up to Congress now to take back its oversight and decision-making powers. It can and should reestablish its prominent role in high-stakes decisions over whether to start wars. A tactical, bipartisan effort was already underway before Trump’s strikes. In it, Sen. Tim Kaine, Rep. Tom Massie, and other members of Congress were proposing a simple measure that would have proactively constrained the White House in this specific case by requiring explicit congressional authorization or a formal declaration of war before U.S. forces could take direct action against Iran. It faced long odds on Capitol Hill given Republicans’ reluctance to challenge Trump’s power, but it would have at least prompted a vibrant debate as lawmakers in both parties warned against involving the United States in the conflict.

The measure was a direct invocation of the War Powers Resolution, a 1973 federal law intended to be a check on the president’s power to enter an armed conflict without the consent of Congress. While it would still allow Trump to authorize military action in self-defense in the event of an imminent attack, it would have compelled him to seek approval before carrying out any offensive operations against Iran. (Read more about this resolution here).

But there are still more systematic proposed reforms that would place healthy constraints on war powers regardless of who the president is. They are even more urgent in the wake of Trump’s unilateral strikes.

Last year, a cross-ideological group of members came together to introduce the National Security Powers Act, backed by Sens. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.), Mike Lee (R-Utah), and Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), which would close some of the interpretive loopholes that presidents have exploited and automatically terminate funding for military action after 20 days if Congress has not authorized it. Similarly, the bipartisan National Security Reform and Accountability Act, was introduced in the House by Reps. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) and Nancy Mace (R-S.C.).

These are neither partisan nor new ideas. Bassin wrote about the need for more congressional oversight of the Obama administration’s possible strikes in Syria in 2013: “How Obama can get out of the Syrian bind he's in.”

The risks of poorly considered and unilateral decisions by the White House are devastating, risking thousands—if not millions—of deaths. The Founders gave us tools to prevent that sort of outcome. We haven’t used them in a while. We didn’t use them this time. But we should insist on them now to avert a worsening of this conflict—and prevent future ones.

An earlier version of this piece first appeared in Protect Democracy’s If You Can Keep It newsletter.

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

A really good post. The problem is that courts found every excuse to avoid war powers issues after Vietnam and Congress has largely decided not to act. The result is that the executive branch--with a leaning forward OLC--has come up with a legal standard that can justify virtually all military action without congressional authorization. If bombing Serbia for two months, invading Panama and Grenada, or sending 20,000 troops to Haiti to force the President to leave is not "war" requiring congressional action--all actions supported by OLC--then nothing will qualify as war. The only remedy is to force Congress to act--which is the theme of the proposals you cite. https://notesfortheperplexed.substack.com/p/did-the-strikes-on-iran-violate-the?r=kjxd5

I agree that Congress should claw back lots of its constitutional authority that it has either squandered, wrongfully delegated, or let die on the vine—from war powers to Chevron. But I could see different people defining the word “unprovoked” quite differently.