The Supreme Court's Ban on Universal Injunctions Will Kneecap Americans Fighting for their Rights

The conservative justices have issued a sweeping and ideological ruling that'll allow the president and government at all levels to get away with unconstitutional violations

Yesterday, the Supreme Court handed down its ruling in Trump v. CASA, where it reviewed lower court decisions to stop President Trump from implementing his executive order on birthright citizenship pending a final ruling. The court did not say whether the administration’s executive order that withholds citizenship from those born in the country to mothers who are not lawfully present or only lawfully in the country on a temporary basis is unconstitutional and illegal under longstanding precedent. That fight will continue in the lower courts, and one way or another, the administration will eventually lose—although not after lots of confusion, fear, and maybe even attempted deportations of newborns and their families across the country.

But the other big headline here is that the Supreme Court essentially destroyed so-called “universal injunctions.” This will make it much harder to stop the government from abusing rights. It will also have all kinds of predictable and unpredictable consequences.

With the caveat that human thought bends more slowly than the news cycle, and that the true consequences of the court’s nuking of universal injunctive relief against the government may take some time to come to light, here are my initial thoughts.

The Supreme Court’s Injudicious Maximalism

First, the ruling was the most sweeping and maximalist of the various anticipated outcomes. It held that federal courts may not issue injunctions against the government that prohibit it from enforcing a law against anyone other than the plaintiffs in the specific lawsuit. After oral argument, it seemed that there wasn’t a strong majority for this strong drink—but whatever nerves the six conservatives showed then seemed to have been steadied afterward. That bottom line certainly provides clarity, but not of a kind that will promote liberty and equality going forward.

Second, although there was no discussion of how universal injunctions operate outside the context of the federal government, the court’s opinion by Justice Amy Coney Barrett seems to apply just as much to lawsuits against states and cities as against the United States. In my last piece for The UnPopulist and in a follow-up blog post, I warned that the impact on future civil rights litigation would be much greater in lawsuits against those levels of government. I had noted that whatever the justified criticisms of any overuse of universal injunctions against the federal government, they don’t transfer to these smaller units. Yet there’s nothing about the distinction in the opinion, or even an awareness that the distinction is a big deal.

The court’s reasoning simply is that (a) universal injunctions didn’t exist in 1789 when the Constitution was embraced, only injunctions that applied to named plaintiffs, and (b) the law that Congress passed in 1789 giving federal courts what lawyers call “equitable powers” (the power to issue injunctions being one of those) only gave them the powers that existed then, so (c) federal courts don’t have the power to issue universal injunctions today. That seems to apply to any kind of government, big or small.

There is a slender reed that I’m sure some plaintiffs’ lawyers will grab onto: at least when it comes to lawsuits against cities, the numbers of people affected are sufficiently small that they’re analogous to “bills of peace” and therefore are within the powers of equity as they stood in 1789. “Bills of peace” were around in 1789 and were used to consolidate the common claims against a defendant to avoid repetitive lawsuits by binding all involved parties to the outcome of a single case. So the argument is that universal injunctions are basically the modern-day version of them. However, the court also states that today’s class actions are the modern-day analogy to bills of peace, not universal injunctions, so that argument might not get very far.

Limiting Even the Class Action Option

Third, regarding class actions, Justice Barrett’s majority opinion did not say anything about the distinction between preliminary injunctions and permanent injunctions—that is, injunctions issued early on in a lawsuit versus at the end. Anyone who wants broad relief in a lawsuit against the government will now be trying to make it a class action. But will they be able to at least obtain preliminary injunctions before a class is certified—a process that can often take months or years? Justice Alito, in his concurrence that Justice Thomas also joined, warns against loosening up on class action standards just because universal injunctions are not available. But he doesn’t outright say pre-certification class action injunctions are illegitimate.

There will be a lot of fighting about this issue to come, especially in cases against the federal government where class numbers are by definition bigger—and class action procedures are often much harder to manage. Alito goes so far as to say that nationwide classes should only be available “in some discrete scenarios.” So are class actions going to get harder to use now even as universal injunctions have now been banned?

Procedural Gaming by Governments at All Levels

Fourth and finally, as someone who has litigated a number of cases where I asked for a universal injunction on behalf of my clients—and sometimes even obtained one!—I am most curious about the practical effects of how this changes the incentives for both civil rights and government attorneys.

In my earlier piece for The UnPopulist, I gave the example of a lawsuit against a city that had passed an unconstitutional ban on political signs. Without universal injunctions, even if the city lost, it would be prevented from enforcing its ban only against the plaintiffs, but everyone else would be fair game, leading to the absurd outcome that some people would get to enjoy their free speech rights while the others did not.

But conjure up any hypothetical law, perhaps one where it’s likely unconstitutional but there’s an outside shot the government might win. In the past, if a single resident brought a lawsuit and obtained a universal injunction, the city attorney would likely appeal if they thought they had a chance of winning, even if the chance was small. The cost would be a few hours in attorneys’ fees, so why not? And even if the injunction only applied to the one plaintiff, the city might appeal because there could be a second lawsuit that itself would get a universal injunction.

But in our brave new world of no universal injunctions there is now a great incentive for the city not to appeal. If the city appeals, it could create bad precedent. If it doesn’t, its only disadvantage is that it can’t enforce the law against that plaintiff—but it can against everyone else. Why? Because trial courts don’t set binding precedent, even on themselves. Perhaps the city won’t do this because in each lawsuit it loses it likely has to pay attorneys’ fees and it will get tired of that bleed on the treasury. But if the law is important enough to the powers that be, that might not matter. So it will take a full-blown class action to truly shut the law down.

This is just one example of how litigation tactics change now that universal injunctions are off the table. Another is how the CASA opinion will affect state courts. States court systems have their own rules of procedure and their own understandings of equitable powers. Thus the ruling doesn’t necessarily change anything there. But many state courts may move in the direction of SCOTUS. And in most state litigation against the government, plaintiffs cannot get attorneys’ fees when they win. Thus, it will be much less of a bleed on city and state treasuries. Therefore, the effects there could be even worse for constitutional rights and put even more pressure on class actions.

There are other knock-on effects that I’m sure we haven’t even discovered yet. But with such a dramatic change in the law, we’ll all see them soon.

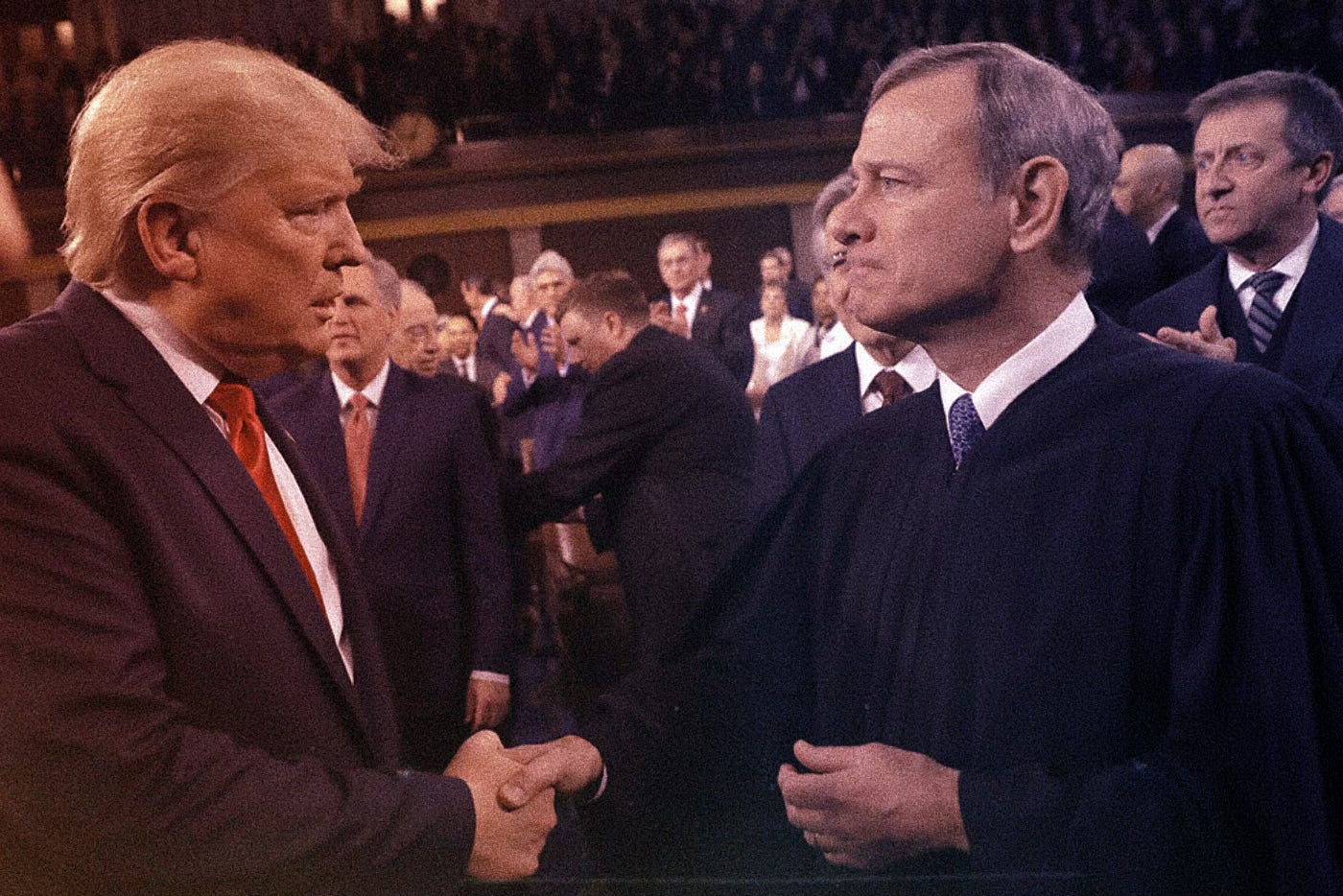

This ruling is yet another example of a pattern we have seen by the Roberts Court during the Trump administration, starting with the immunity ruling: Erecting ever more barriers against citizens seeking relief from invasions of their rights and reducing barriers against an over-weening, authoritarian executive. There are some bright spots, such as my colleagues’ victory in Martin v. U.S. earlier this month, the wrong-house-raid case. But overall many justices seem more interested in advancing their academic theories of how the government should be arranged rather than ensuring that the executive, not to mention officials at the state and local levels, respect the constitutional rights of Americans—and the constraints on their powers. In the court’s quest to obey some archaic reading of the letter of the law—that isn’t even correct!—it is ignoring its spirit.

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

O’ but the irony, https://republia.substack.com/p/the-irony-of-demagoguerys-self-abdicating

Thanks. I am aware of that. My point was that I thought 'the process' involved exactly that. Cases start in lower courts, then work upwards. Meaning that I think slamming the door on nation-wide application of decisions of Constitutional issue from lower courts is a travesty. Is the Constitution 'national', or not? NOTE: Nothing resembling a legal education on my end.