Facing Down ICE in Portland as an Inflatable Dachshund

I barked at the agency led by a puppy killer and survived to tell the tale

Early last month, on a protest-filled Wednesday in Portland—which, in the popular imagination, is every Wednesday in Portland—I wandered over to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement field office. “President Trump will end the radical left’s reign of terror in Portland once and for all,” White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt had recently promised, referencing National Guard troops sent to “protect war-ravaged Portland and any ICE facilities under siege from attack by Antifa and other left-wing domestic terrorists.” While I would have loved to make my debut as a war correspondent, I knew from experience that the Portland conjured up by the Trump administration bore no resemblance to the city I call home.

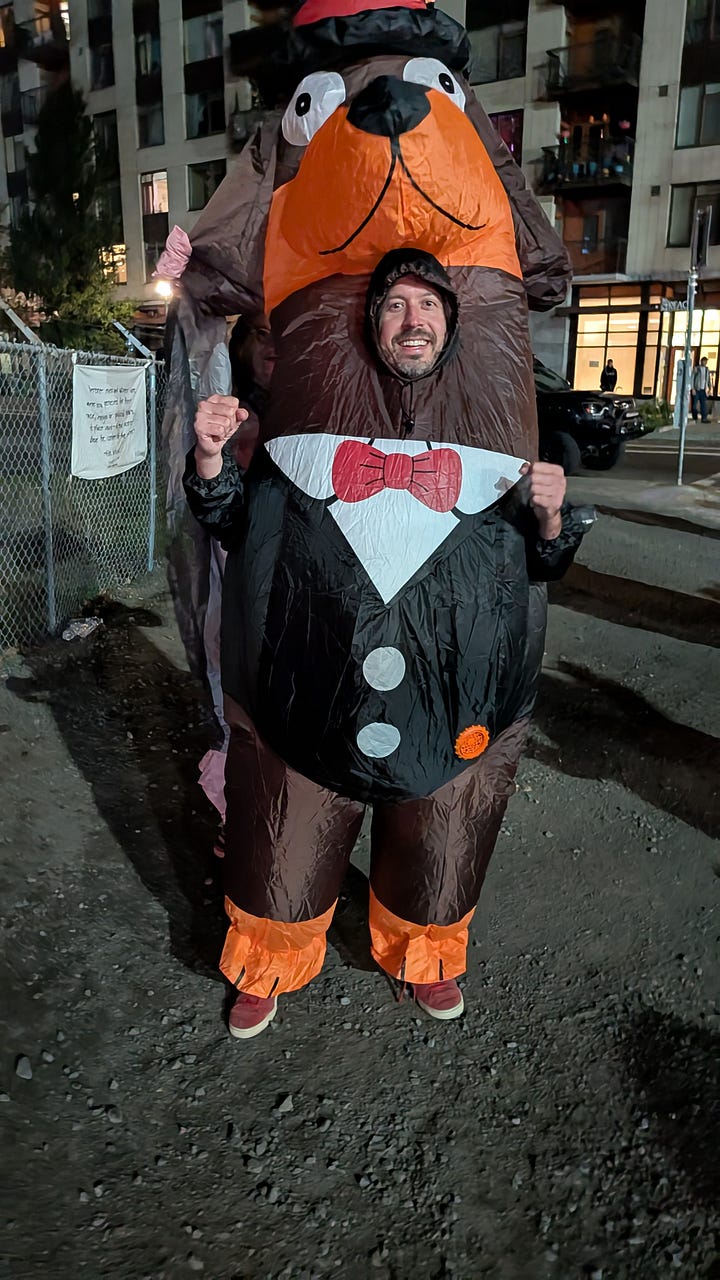

That said, I didn’t quite know what to expect at the ICE facility. The day before I went, federal agents had yanked a comedian performing karaoke in a giraffe costume off the street. A week before that, officers barreled into a banana-suit wearing brass band, arresting the clarinetist in the resulting melee and jailing her for three nights before charging her with assault. I was relieved that among the first people I encountered was a couple taking their two corgis for an evening stroll. If the scene was safe for corgis, I figured it was safe enough for me, a man dressed in a giant inflatable dachshund costume.

This was very much not my typical Wednesday night. Though I live in Portland, where protesting is one of the city’s favorite pastimes, my preferred mode of political activism is sitting in a coffeeshop typing words on a screen. I’m less inclined to assemble in large groups in which my message is limited to what I can convey on a sign or t-shirt, surrounded by other protesters whose views may be at odds with my own. In Portland, the message of late had been reduced to pure absurdity, images of human-sized frogs staring impassively back at lines of federal officers in riot gear. As the protest went viral, I found myself intrigued to join. “What is it like to be a bat?” the philosopher Thomas Nagel famously asked. I wanted to know what it’s like to be an inflatable frog.

That experience would have to wait—inflatable frogs had become such a popular symbol of resistance that hundreds had already been purchased from Amazon, depleting the entire stock. No problem—there were plenty of other animals on offer. Should I go as a zebra? An anglerfish? An axolotl? There were practical matters to consider. A costume with an opening for one’s face seemed most comfortable, but also more vulnerable to pepper balls and tear gas. The lobster looked fun, but how was I supposed to take notes and pictures with my phone while wearing inflatable claws? A giant dachshund in a top hat won me over, though I admit I hadn’t thought through the potential risks of dressing up as a dog to protest an agency commanded by Kristi Noem.

Fortunately, no trouble arose on the night of my visit. I was greeted by fellow protesters offering candy for energy, and I gladly accepted a fun size Kit Kat bar before joining a menagerie of animals enjoying a dance party across the street from the ICE facility. Alongside a frog, a t-rex, a chameleon, a Teletubby, a couple of forest gnomes, and other creatures large and small, plus a few people in normal human garb, we danced the night away to everything from Haddaway’s “What Is Love” to Ice Cube’s “Arrest the President.”

If there’s one thing you should know about wearing an inflatable animal costume, it’s that you have no proprioception. You’re going to bump into things. No one expects you to look cool dancing in an animal skin. You can shimmy, shake, and gesticulate. The inherent ridiculousness of the situation is liberating, and between the adoption of an animal persona, the non-stop encouraging honks from passing cars, and the fist bumps from other creatures, the dance-pop party was genuinely fun. Certainly more fun than the ICE agents seemed to be having; a half-dozen of them were perched on the roof, armed and gazing down on the dancing protesters.

The only time the tone shifted was when the agents would open the gates to the driveway, emerging in formation to clear space for their cars to come and go. This was the cue for protesters to advance in to verbally berate the agents, with the DJ dropping music to mock them, too: the “Imperial March” from Star Wars, “Every Breath You Take” by The Police (key line “I’ll be watching you”), and, as the agents retreated back inside, the theme from Curb Your Enthusiasm.

This was all well-rehearsed, each side knowing their boundaries and their role to perform, occurring four times without incident in the just over an hour I was there. For all the competing narratives about the protests, portraying them as terrorism or harmless fun, the truth is that for the most part they are just people standing around. The dancing animals bring some levity, but I knew that I wouldn’t be among the long-haulers coming back day after day for hours on end, as much as I appreciate their efforts. Eventually the giant canine head above me began to sag and I realized that the batteries powering the air intake fan on my costume had run out of juice, so it was time to pack it in.

Dressing up as an inflatable creature to protest is obviously ridiculous. It’s also, in its own way, a brilliant tactic in today’s terribly degraded information environment. To live in Portland is to live in a city about which the president of the United States lies constantly. “Every time I look at that place it’s burning down,” Trump said recently. “There are fires all over the place. When a store—there are very few of them left—but when a store owner rebuilds a store they build it out of plywood. They don’t put up storefronts anymore. They just put wood up.”

How is one supposed to respond to statements so wildly disconnected from factual reality? When our own officials tell the truth, Noem tells Trump that “they are all lying and disingenuous and dishonest people.” The wave of facts breaks against the wall of misrepresentations, the vivid imagery of the 2020 protests in Portland overcoming any attempt to communicate the present-day reality. Flawed reporting that recycles footage from 2020 as if it represents the current reality in Portland reinforces that misperception.

I’ve written thousands of words for multiple publications attempting to provide a more accurate view of Portland, but the fact is that one person in a frog costume has done more to change perceptions than I possibly could. The frog and the animal army he inspired have proven a potent counter to the narrative of a city on fire. Dancing frogs and unicorns standing up to a line of federal agents in riot gear is the kind of image one might ask AI to conjure, something fantastically absurd to catch the eye of a passive scroller. In Portland, it’s real life.

This reminded me of a passage in Christopher Hayes’ excellent book on the attention economy from earlier this year, The Sirens’ Call. Reflecting on the work of Neil Postman, Hayes writes: “what I take from it is that in competitive attention markets, amusement will outcompete information, and spectacle will outcompete arguments.” Continuing a few pages later:

In our own attention age, the most important trait is the ability to get attention, above all else. The shamelessness to interrupt. While under a functioning attentional regime, other abilities might distinguish one in the public sphere; as the attentional regimes collapse, the ability to get attention becomes more and more essential. And like the violence in a failed state, there is no static equilibrium. The competition for attention is ceaseless, constant, dynamic, and always in flux. At any point attention can be pulled in one direction or another. Power centers and alliances shift.

These basic conditions have revolutionary consequences for public discourse in the attention age, an age in which the debate model has almost entirely fallen apart.

In an information environment characterized by infinite scroll and short-form video, striking imagery can be more compelling than detailed reporting or a well-crafted essay, however troubling we may find that to be. Consider the public’s perception of Portland since 2020, which has often been reduced to whatever photo or short video captures the collective attention, one dramatic scene shaping the view of the whole city. This was misleading during the 2020 protests, but those were at least extended in time and geography and sometimes destructive. The description of Portland as a war-torn wasteland is completely absurd now.

As current Portland chief of police Bob Day explained to James Ross Gardner for a recent piece in The New Yorker:

The area in question in 2025 ... is a single block in a city that stretches a hundred and forty-five square miles. So, only with a lens focused tightly enough, at just the right moment, and on just the right stretch of one specific city block, can you make the case that there is chaos in Portland.

Of course, that’s precisely the case the Trump administration is trying to make, which is what makes the inflatable frog costumes such a smart response. Relatively few Americans will read reporting in outlets like The New Yorker, but millions will see the frogs, dogs, and unicorns bip-bopping in the street, making it far harder to sell the narrative of a war-ravaged hellscape. The frogs offer an “irresistible image” in the words of L.M. Bogad, a professor of political performance at University of California, Davis, who links the current Portland protests to a long tradition of “tactical frivolity.” The inflatables have become a meme standing in for the whole city. Where once people thought of flames and tear gas and black bloc protesters, now they think of colorful animals dancing.

This is arguably not great for American discourse. But you fight with the tools you have. (See also this piece from Sarah Jeong, who writes appreciatively of the frogs but laments that too often “people are simply posting at each other instead of engaging with reality or solving collective action problems.”) As someone who follows political news closely, it’s endlessly frustrating to see so many Americans failing to see the ways in which the second Trump administration presents a decisive break with normal politics, an unrelenting assault on our constitutional order. Yet there are signs of optimism, notably the recent No Kings protests, which drew truly massive numbers of people out of their houses and into their communities, all across the nation, to express their opposition to Trump’s dictatorial ambitions and above all his cruel, violent, and due-process-violating campaign against immigrants. (I was at those protests, too, though in a more practical Superman sweatshirt rather than my inflatable dog costume.)

Judging from the recent blue wave election, that message is breaking through. I’ll leave the detailed analysis to others, but the simplest explanation for the result is that Trump’s narrow 2024 victory represented not a generational “vibe shift” but rather a misjudgment on the part of low-information voters who didn’t believe the warnings about how bad his second term would be. Now they’re finding out and they hate it. It’s a tragedy for our country that they didn’t figure it out sooner; we could be living under a normal Democratic president who, whatever her flaws, would not be throwing the country into constitutional crisis, lighting our cultural capital on fire, and attempting an essentially fascist consolidation of executive power.

We’re a long way out from the midterms and even longer away from the next presidential contest, and many things are going to get worse before they get better—but the optimistic view is that we’re seeing the makings of a united liberal coalition against Trumpism that includes leftists, urbanists, libertarians (though not enough of them), and disaffected Republicans and neoconservatives. We can work with that and we can work out our disagreements later. Until then, frog on.

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

As Charlie Chaplin demonstrated eons ago (not really but it seems so), and Starlord did more recently, making fun of them is a really powerful way to stand up to a tyrant…

This report made my day! Thanks.