Listen to Zooming In at The UnPopulist in your favorite podcast app: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google Podcasts | RSS | YouTube

Landry Ayres: Welcome to Zooming In at The UnPopulist. I’m Landry Ayres.

Today, we’re excited to welcome back The UnPopulist’s editor-at-large, Tom Shull. The last time we spoke with Tom was back in January, when he shared insights from the groundbreaking survey he developed for the Institute for the Study of Modern Authoritarianism, the publisher of The UnPopulist, focused on populist attitudes and beliefs in the electorate. Now, nine months later, Tom is going to walk us through the results of a new, even more comprehensive survey. His essay summarizing some of the survey’s main findings for Trump supporters was just published at The UnPopulist and ismaglobal.org, and more findings will be released there in the coming weeks.

So what’s changed since the last survey? What are the key insights? And how has our understanding of populist sentiment evolved? We’ll cover all of this and more in today’s conversation. We hope you enjoy.

A transcript of today’s podcast appears below. It has been edited for flow and clarity.

Aaron Ross Powell: You and I last spoke in January of this year on this same podcast about a survey you had put together for the then-very new Institute for the Study of Modern Authoritarianism and The UnPopulist about populist attitudes and beliefs among the electorate. And so now nine months later we are speaking again.

You have a new survey. (First let me encourage listeners to go back—it’s the Jan. 22, 2024, episode of the show—and listen to that interview.) But why are we talking again? What’s new with this new survey that you have just put out?

Tom Shull: There are a couple things that are new. First of all, it’s a longer survey, so it gives us a little more insight—and not just into what people are thinking on a wide range of issues. It also allows us to broaden somewhat our understanding of what the populist attitudes amongst the public are leading people to conclude and to feel, and of that question of trying to quantify the level of populist sentiment in the country and how people who might qualify as populist under our definition see things.

That’s one of the key points if you want to make sure that a populist attitude has, I guess, a less harmful outcome than it could have when people become so wedded to a particular idea, a cause, a leader that they’re willing to see laws broken or circumvented by their particular populist candidate and we end up in the kinds of problems that we saw on Jan. 6, 2021, where there was a definite concern that effectively there was an attempt to overturn the election. Even for the people who do not see it that way, it’s not an implausible way to construct it. I think that that concern, that desire to understand, is really important.

Powell: What is the definition of populism that we’re using for purposes of this survey?

Shull: So let’s be very clear here. Populism is a disputed concept. There has been an increasing amount of academic work done over the past couple of decades in an attempt to see whether populism is something more than just a kind of general sense that there’s a candidate who is rough and ready and gets along with the average man on the street, and by golly, they tell off those guys up in City Hall or those guys in Congress. It’s instead trying to define much more clearly what constitutes populism and include a recognition that you can see populism in different kinds of political settings. On the left, on the right, we see populist parties: It’s a little more common on the right in Europe; it’s a little more common on the left in South America. But it is something that travels.

Now, for this survey, we worked off a series of attitudes from summaries in the academic literature. That is therefore not to say that each and every one of these things every populist scholar would agree with. But I think they would see them as being within the constellation of the populist ideas that are discussed in academia.

So let me give you our four. One of them is a very close personal connection with the leader or with the leader’s agenda and a sense at the same time that that leader understands people like me and will fight for people like me—that they will actually do those things, not just say they will. That’s one. Another is a sense that people are being harmed by elites within society, and that these elites are in some sense selfish or corrupt and willing to let the people suffer or not prosper as a result of their decisions.

Another is to identify what we’re calling “social outgroups.” These are people who in one sense or another are seen negatively by people with populist attitudes. They also are seen as having, in some sense or another, enjoyed special advantages, either through the benign neglect of the elites or through positive action by the elites, and further that, in a sense, these people are outsiders—that they can’t really be true members of the national community.

Finally, the fourth is that someone would, as I was mentioning earlier, conceivably support seeing their candidate cut corners legally and do things that aren’t actually constitutional, aren’t appropriate, or aren’t part of the democratic process and the constraints that we put on political power.

Powell: And so someone whom you categorize as being a populist is someone who displays three of these four factors, correct?

Shull: Correct.

Powell: So, if I remember correctly, the data from the prior survey, the one that we talked about in January, had been gathered in November 2023?

Shull: Correct.

Powell: This one is based on data from August of this year—so, a month ago as we’re recording this. And in this new survey, you see higher rates of populism than we did in the prior, shorter survey. Are those higher rates the result of adding this fourth factor, basically casting a wider net for populists, or do you think that we’ve seen an increase in populism over the last year or thereabouts?

Shull: To some extent we broadened our definition. That was based on the findings of the first survey. In the first survey we could test only three of the attitudes. The survey was brief, and we did not have the kind of room that was necessary to look after the social-outgroups question.

As a result, we just looked at people who had only those three characteristics. In this survey, where we had four characteristics to choose from, you could essentially miss on one. Still, we would include you as part of that coalition of populists who act together, even though they don’t agree on every single thing.

Just briefly, let me explain why we think three of the four is good. One, we find that by and large, once you get to three of those attitudes, we’re seeing a shift in the feelings, the things you express, the way you view things. And as a result of that, we are already seeing the populist dynamics at work. What I would also say is that when you consider serious scholars of populism, they would look at this list, and as I mentioned, they would say, “Well, you know, okay, I get it. You’ve got a constellation of ideas here. But I have to tell you, this one is not as important. This one you’ve got maybe is only half as important.” And so the sense would be that you could have various scholars saying, “I like this part, but not so much this part.” They would be pointing to different things.

And our view is that when you get the folks [satisfying different populist definitions] into a political movement together, it may be that there are some things they don’t quite agree on, but that together they will move as a bloc in a more populist direction, even if some of them shear off a bit in various ways on various questions. In that sense, it’s just like politics in any other setting.

“With populism, what you see is a sense that there is a group of people who are *the* people in the country. Typically they’ll talk about things that are ‘common sense.’ They’re going to say the will of the people should be carried out and that the elites are failing to do that. They tend to see those elites in moral terms—as failing *morally*.”

Powell: Something that might have stood out to listeners about these four factors, which you refer to as attitudes, is that we’re used to thinking about political disagreements along policy lines. So if you’re a Democrat, it’s because you believe in a certain set of the things government ought to do. It ought to work on healthcare in this way; it ought to do this on immigration; it ought to set taxes at these levels. If you are a Republican, it means you have a different set of policy preferences.

But all four of these, when it comes to policy, the actual questions of what should government do, what kinds of laws, what should be the content of laws are effectively contentless. There’s nothing in these four that says government should raise marginal tax rates or lower them, that government should have a free market in healthcare or socialized medicine and so on. Does that then mean that we should not think about populism as an ideology, but more a particular layer that might exist on top of different political ideologies, different political perspectives, such that everyone who’s a populist doesn’t necessarily agree with each other? They might disagree violently with each other, especially the ones who are fans of overriding institutional limits and using violence to advance their ends.

Shull: I would agree that in one sense there is not an ideology that populism necessarily recommends in terms of the means and the purposes of government. There is no question that you see types of populism that associate with socialism, with nativism, with nationalism. In the literature, they call it a “thin ideology”; it can attach itself to other ideologies. So yes, you’re correct. It’s not talking about what government would do.

However, what you see consistently is a sense that there is a group of people who are the people in the country. Typically they’ll talk about things that are “common sense.” They’re going to say the will of the people should be carried out and that the elites are failing to do that. They tend to see those elites in moral terms—as failing morally. The social outgroups, on the other hand, may be segregated for other reasons—for nativist reasons, maybe for class reasons. But that distinction does tend to reproduce itself frequently in populist settings. And again, these are things scholars argue over.

Powell: I want to get in a moment to the actual findings of the survey. But before we go there, can you give us a sense of how you design a survey like this? You’ve identified these four features of populism, and anyone from whom we see evidence of three or more of these four we’re going to count as a populist.

But the survey isn’t four questions saying, “Do you feel an unusually direct connection with a political leader? Do you like elites? …” It’s not that direct in its design. So how do you get from those four features to a battery of actual questions you can ask people on a survey over the phone, etc.? What does it look like to design those?

Shull: Yes, well, to some extent, we have the benefit in this case of having conducted the survey online, as opposed to on the phone. It makes it a little bit easier for someone to digest those questions.

We do try to keep them reasonably short and easily understood. When we have done this, typically we have a couple of questions, two to three, for each of those attitudes that I’ve talked about. And at the same time, I want to know something about the people who are answering those questions. So there is a slew of demographics that go with it, about age, income, gender, educational background, etc. And then, of course, we will ask some questions about policy. We will ask some questions about whether you think it’s right or wrong to do the following things that may involve cutting corners with constitutional norms, etc. We’ll ask questions about what you thought of Jan. 6. We’ll ask questions that have a chance to further probe and understand the sentiments and the feelings of the people who are answering them, particularly those who identify as populists.

Powell: What results stood out to you as particularly interesting?

Shull: There are two sets of results that I will just briefly summarize. I think they were particularly interesting because they speak to us, I think, even independent of populism per se. Both of those are two of the social attitudes—one toward elites and the other toward social outgroups.

What we saw in the first survey about elites carried over again. You have large majorities of people saying that they strongly agree or agree that elites—national elites like our elected officials in Congress, and again, even bureaucratic elites, people who work for the federal government and federal agencies, etc.—are essentially harming people like the respondent by pursuing their own selfish interests.

Honestly, when I first wrote that question, I thought, “My word, this is so strongly worded. These people are harming me because they have effectively followed their own selfish interests?” I almost wondered if we had simply overdone it. And instead we got a tidal wave of, “Yes, I absolutely agree with that.” They agreed with it a little bit less for the bureaucratic elites—by and large, it was 60%-plus. It went up to 70%-plus on national elected officials. In that kind of an environment, governance is inevitably going to be harder.

So a lot of the things that we look at as being difficult in our society right now because of political disagreements are compounded by the fact that the very people who are trying to carry those things out are viewed in general in a very negative light, even if it’s through a partisan filter. So I look at that.

I also look at the degree to which people were willing to identify social outgroups. I’m not going to say that it was horrifying; it certainly wasn’t. You can look back at times in American society where resentment against, let’s say, minorities, resentment against immigrants, was very high, much higher than it is today. These things have changed over time. so we are not facing that earlier kind of crisis.

“Amongst Trump supporters, we had roughly 36%—that’s our estimate of the number of populists amongst the people who are supporting him in our survey. When you talk about the number amongst Harris supporters, it was much lower, at 15%. For Kennedy, it was around 29%.”

But what we did see, Aaron, is that it was very difficult to find people who didn’t have at least somebody or some group that they had pretty strong negative feelings about. So 72% of Americans didn’t just have negative, but very negative feelings toward at least one of the groups that we studied. Now we looked at 12 different demographic groups. And we looked at four different political groups: people on the right, people on the left, Republicans, Democrats. But amongst the demographic groups, we were talking about various races: white, Hispanic, Black. We looked at questions of religion: evangelical Christians, Muslims, Jews. And we asked people essentially a battery of questions about whether they thought there were special advantages given to this group, whether they viewed them negatively, whether they thought they could be true members of the community.

Even amongst people who didn’t ultimately say that they view this person as part of a social outgroup—that is, negatively on all three of those dimensions—you still had an awful lot of them saying (and it was like 64% of the people who were surveyed said), “I think one or more of these groups enjoy special advantages at the expense of people like me.” Again, 72% were holding very negative views toward at least one of those groups. And amidst that thicket of conflicting feelings, it only makes more difficult, again, these questions of the social decisions we have to make together. And here we are in the midst of a crisis of legitimacy in terms of the people who are amongst our leadership and the federal government being seen as elites who are in fact harming people.

These things are not going to go away overnight, and they’re unlikely to go away just because of an election. And that’s kind of what stood out to me. You’ve got these two very large social attitudes, and they’re going to be tricky to essentially diminish.

Powell: It does seem that you could answer in a way that this survey would indicate as a populist direction on those kinds of questions, but not necessarily think of yourself as a populist. Or maybe you could make the case that you’re not. So you might say, “Yes, I think that there are disfavored outgroups”—like, say, “White Christian evangelicals are pushing a social agenda that would hurt all sorts of minorities, and protecting minorities is the correct thing to do, but I’m not a populist for believing so.”

Or you might say that not all elites are using their power for selfish ends or lying to advance their own personal interests, but certainly as we’re recording this, it seems like everybody in the administration of Eric Adams in New York is being indicted or being investigated. But that doesn’t mean that every big city’s mayoral system is equally corrupt. But if you ask, “Are there elites who lie and advance their own interests?,” I’m going to say, “Absolutely.” And in fact, someone who said, “No, they’re all honest,” we would think is just tremendously politically naive.

And then, like, overriding checks on state power. This is a country that was founded in revolution. And most of us celebrate the Founding Fathers every July Fourth for doing the number four attitude on your survey. And so, I guess, when people are answering these questions, is there a way that someone could, say, sign on to three out of these four—the first one seems a little bit weirder, the first one about this direct connection with the political leader as my avatar—without really being a populist? And if they can, what does that say about this broader question of what we should do about it? Anger at some people is sometimes justified.

Shull: Agreed. And in fact, again, when I talk about those two social dimensions, whether it’s social outgroups or the feelings about elites, I look at those as being challenges to overcome, even if you feel that what you’re saying is an absolutely legitimate thing. I would guess most of the people in our survey do; they could rationalize and explain exactly how they feel. At the same time, it now presents a barrier if there is this lack of respect. And that’s kind of the broader point I was trying to make when I said all of that.

But let’s go to your point. Your point, I think, is an absolutely legitimate one. We are careful not to say that someone expressing signs of one of these—that’s how I always think of it, signs of a populist attitude—is in fact a populist, and we’re very careful to make that distinction. They are not. We do not think that they are necessarily so.

It’s only as these different views combine that we begin to see changes in terms of how they view things that can be more problematic, including the idea of cutting corners, of violating laws. And I would say two things. One, if you look at the number of people we qualified as populists, it’s a minority of the population. So yes, there were majorities who said certain things that we could detect as a potential populist attitude on one dimension or another. But we did not see that there was this vast outpouring. So very briefly, let me just tell you, amongst Trump supporters, we had roughly 36%—that’s our estimate of the number of populists amongst the people who are supporting him in our survey. When you talk about the number amongst Harris supporters, it was much lower, at 15%. For Kennedy, it was around 29%.

And of course, the Kennedy group is very small. It’s now dissipated. But there was a sense, I think, in general, that he was a kind of populist manifestation. We see the numbers sort of reflecting that, but they are not shooting through the roof because even though there are large groups who are critical of the governing elites, these strong views do not then turn around and immediately wed themselves to other populist attitudes. And that is one of the reasons that we look at this as a kind of broader model.

I guess that’s kind of a key point I would make about this, that it is in fact, the combination of these factors that allow us to feel that we’re seeing something different. If you do have a particularly persuasive and charismatic leader who is in fact a very good person, it may well be you have that personal connection. It doesn’t turn you into somebody who’s ready to storm the Capitol. And that is something that we freely recognize.

So let me just present real quickly, if I may, the various social outgroups that we found. Far and away, the number one social outgroup—where people were negative toward them, felt that these groups had special advantages and that they can’t be true members of the national community (and can’t be, not aren’t, but can’t be)—were illegal immigrants. Now, there you go to your point, right? You could look at that and say: “Well, now, wait a minute. Here we have people who have in some sense or another violated the law. And even if I don’t see that as a thing that necessarily makes them evil, maybe it means I don’t feel that they should be allowed residence in the United States.” So you can, of course, rationalize that kind of point of view.

But as a practical matter, when we look at this, you have a hugely different response amongst Trump supporters, where 48% of them were willing to say all three of those things. Among Harris supporters, only 5% did. Amongst all respondents, it was a quarter.

If you look at legal immigrants, they almost didn’t register. Almost nobody had those feelings. What was encouraging was that you saw very little of that in terms of feelings about Blacks. We included men and women; we included whites, and as I said, legal immigrants: All of these were just kind of off the meter, and they didn’t register. We saw very low numbers, say, for Hispanics.

Jews, amongst Harris supporters, were down at 1% saying this; Muslims, same thing. The place where you see Harris supporters flipping is precisely what you talked about: At evangelical Christians, suddenly it jumps up to 13%.

Now, amongst Trump supporters, we did see more of this kind of identifying of social outgroups. Fifteen percent (15%) said Muslims fit that description of people who they saw negatively, who were getting special advantages under the system, and who just could not be true members of the national community, which is kind of a generic phrase for real, true Americans. And we also saw, and this I think is important to recognize given the culture wars that are going on, that figure went all the way up to 19% for people who were transgender. And we had even 11% for gays and lesbians, even though the general trend over the past couple of decades has been greater acceptance of them. We see that they are registering here as kind of a social outgroup amongst Trump supporters.

So, you know, even among the Trump supporters, it’s interesting that transgenders actually registered as the second largest social outgroup. We wouldn’t be surprised to see that for illegal immigrants, right? We know that Donald Trump’s talked about this. We know that people who are going to be comfortable voting for him are largely going to at least feel that he has a point about illegal immigration. So, in any event, I guess I wanted to add all that, because I think that’s an important and interesting part of the survey as well: Where do we see outgroups? Where do we see pain points?

Powell: I found this particular table of results fascinating, and partly because there are different stories you could tell about it. The different stories could be read as either encouraging or quite discouraging.

So yes, transgender people, as far as who’s the biggest outgroup among Trump supporters, are second only to illegal immigrants. But also they’re at 19%, which means that four out of every five Trump voters did not identify transgender people as an outgroup. If you just asked people in general, “What percent of Trump voters do you think really dislike transgender people?,” they probably guess a number higher than 19%. So that seems encouraging. But at the same time, you can tell a story about the difference in illegal immigrants—48% for Trump supporters. That again actually seems probably lower than most people would guess based on narratives about Trump supporters. But 5% of Harris supporters for illegal immigrants actually also seems lower than you would estimate. Anyone who’s worked in immigration policy knows that Democrats are plenty opposed to immigration as well.

And so that got me thinking about the question of social desirability bias and also political identification. If you are a Harris supporter, you think of yourself as a certain kind of person and so answer this question in line with how you think that ideal person might answer. Or if you ask someone who is antisemitic whether they’re antisemitic, the chance that they say yes is lower than the rate who are actually antisemitic.

So how do we think about that? And this goes back to the really interesting questions for listeners who don’t do this kind of work, don’t spend a lot of time on public opinion surveying, of how you interpret this information in light of the fact that people are volunteering an answer to a question.

Shull: Well, to return to the beginning of what you were talking about, there’s no doubt that these numbers could be worse, right? Honestly, writing these questions literally made me feel ill. My stomach was churning as I wrote these questions because some of these questions involve people who faced discrimination in our country for a long time. And the thought of asking someone to express that—and the possibility that the number would be high—made me sad.

So, I look at some of those findings for minorities, whether it’s Jews or Blacks, even Muslims—though, obviously you could be more comfortable seeing those lower amongst Trump supporters—I guess my feeling is that those numbers actually aren’t bad, right? So I agree with you. I think there is some good news in here, no question.

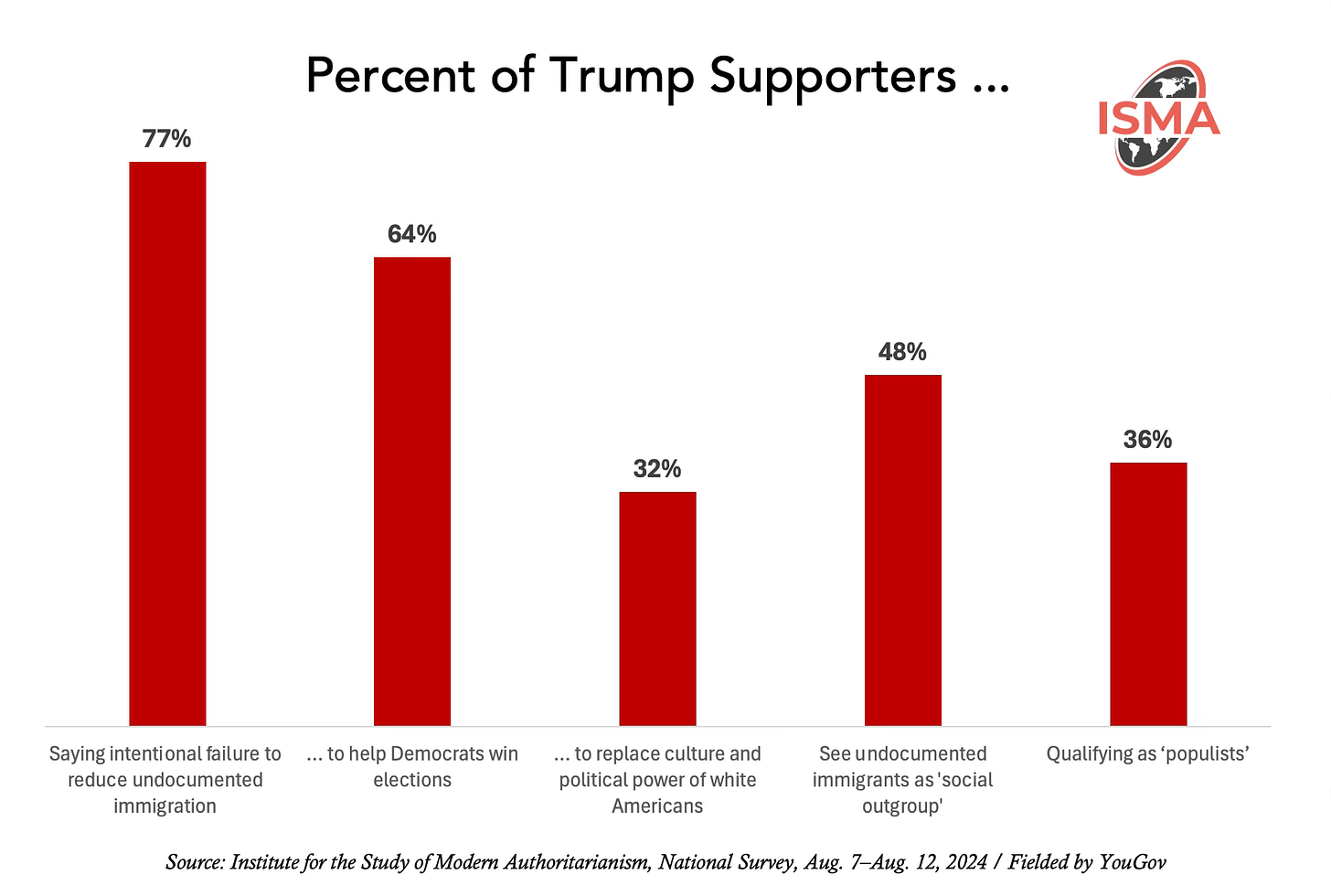

“You have 21% of Harris supporters and 77% of Trump supporters agreeing or strongly agreeing that one of the causes of the level of illegal immigration that’s going on is actually due to a kind of intentional neglect or an intentional failure amongst our national political leaders to try to actually bring that under control.”

But I guess the point I also want to make is that qualifying for all three of those things is hard. If you look at Trump supporters, 58% of them, nearly 60%, have negative feelings toward people who are transgender. That is not registering as 60% viewing them as a social outgroup; it says 60% just view them negatively. So, the individual responses about special advantages, about negative feelings, can be quite high. It’s just that to complete the trifecta, to say not just those things, but, “I don’t look at them as people who can be part of the national community; I don’t see them as part of all ‘real Americans,’ ‘the people,’ what have you”—that’s kind of an unusual thing. It’s a different statement. We don’t see lots of it, but we do see it. And obviously, whenever we are moving through policy questions or we’re moving through social debates that involve those particular groups of the population, we’re likely to see suddenly that there’s a whole lot more conflict than there would be otherwise. And that’s a useful piece of information. It does say be careful here.

Powell: Let’s stick for a moment on the illegal immigrants as the largest social outgroup among Trump supporters. And this ties into the question of elites, because there’s a substantial portion of people who think that political leaders have intentionally failed to reduce undocumented immigration, which is somewhat different from just not having done anything about it. Can you talk about your findings on that question and how it differs among the groups we’ve been talking about?

Shull: Sure. What we found in general, and again, this is not surprising in terms of the partisan differences, is that basically you have 21% of Harris supporters and 77% of Trump supporters agreeing or strongly agreeing that one of the causes of the level of illegal immigration that’s going on is actually due to a kind of intentional neglect or an intentional failure amongst our national political leaders to try to actually bring that under control.

We had that question last time. We had even more people saying this time, “Yes, we think there’s an intentional failure here.” But this time, we had room to ask them, Why do you think that is? And one of the options that we gave them was what you often hear in emails and advertising from folks on the Trump side—that Democratic Party politicians believe essentially that immigrants will vote for them and help them win elections. And if you ask people, just how many of them feel that this is true, 64% of Trump supporters believe that there is essentially an attempt here by Democrats to use undocumented immigrants to help them in their political prospects.

Now, I talked earlier about these issues of people’s frustration with elites. We also asked, “Where’s that come from?” And a lot of them say, “Well, we think these elites lie.” A lot of them say, “We think that they essentially kowtow to special interests.” And when you look at these immigration questions here, you get a strong feeling that this is that same concept of deception and favoritism going on at the highest levels, but it’s very concentrated. This is 200-proof stuff. So, as I said, 64% of Trump supporters are basically saying, “Look, we think that it’s because you think it’s going to help Democrats, and that’s why you’re doing it.” And you have 33% of them saying that it’s because essentially our leaders, probably in confluence with business interests, want cheap foreign labor.

And, you know, you can see some of that resentment in Trump’s original campaign in 2016 when he would go to areas where factories had left the United States. And there was a feeling that there had been for average Americans a kind of gutting of job opportunities, and you see that reflected here as well. Perhaps the strongest signal that we get is that 32%, almost as many of the Trump supporters, feel that the “intentional failure” is because our national political leaders want undocumented immigrants in the country to replace the culture and the political power of white Americans. Now, you would be familiar with this, especially as a reader of The UnPopulist and a contributor to it, as the idea known as “Great Replacement Theory,” something that was imported from Europe, the idea that essentially this “unbridled” immigration is really an attempt to take white American culture and drown it out.

That feeling does have a very populist feel, right? The sense of a true people who are essentially being put at a disadvantage by the elites in the elite’s pursuit of their own special interests. And so earlier, we were saying that there can be reasons that people might have these views, right? And they can be legitimate reasons. And it may well be that some people who register on this—who said, “Look, I think this is an intentional failure”—may well feel that they’ve got evidence of this. How in the world does this go on for a couple of decades, in effect, and we still aren’t getting anywhere?

But by the same token, springing up alongside of that are some ideas that are pretty harsh, pretty cynical, and ones that involve strong passions, especially when you invoke race like that. And yes, some of the people who think it’s intentional may have a very clinical view, but the idea that this is done as a kind of cultural warfare, that’s the more populist sentiment, and the people who are in that camp are more likely to qualify as populists under our model.

“One of the interesting dynamics that we see independent of populism in the election is people with a sense of fear about what’s to come. … We see that you’ve got about 42% of Americans saying that Donald Trump would definitely pose a threat to democracy. But what we also see is that a lot of people are saying the same about Kamala Harris.”

Powell: As we’re recording this, I think it is 50 days out from the presidential election in November. And it’s an election where a lot of the attitudes, beliefs, and values that we have been talking about for the last 40-some-odd minutes are extremely relevant to the broader political conversation and debate. We saw in 2020 a populist candidate lose, and a populist backlash that included a violent insurrection. There are worries about populism going into November. Can you talk about all of this in that context as we look ahead to this election and the lessons of prior elections?

Shull: Yes. One of the interesting dynamics that we see independent of populism in the election is people with a sense of fear about what’s to come. And we looked at the question, for instance, of whether people see particular candidates as posing a threat to democracy. And not perhaps surprisingly, given everything that has been going on in terms of the public debate, in terms of the earlier Biden campaign, certainly, we see that you’ve got about 42% of Americans saying that Donald Trump would definitely pose a threat to democracy. But what we also see is that a lot of people are saying the same about Kamala Harris.

Now, this obviously has a partisan valence. I don’t want to deny that for a moment. And it was kind of interesting to look at the small cadre of Kennedy supporters and see that they kind of split. They saw threats from both Harris and Trump.

We did find that there were a lot of expressions of fear about certain candidates being elected. And then, it kind of all goes back, I think, to the question of what happened with the last election. No matter how you feel about what happened after that election, it certainly isn’t what’s happened before, and I don’t know that anyone would consider it optimal. We had people entering the Capitol building during this attempt to certify the vote. And we asked, “Did you approve of what happened there”?

What’s very interesting is that there is, by and large, a disapproval. And that does not have the same kind of strong partisan split that you see elsewhere. Yes, there’s a split. There’s no question there’s a split. But by the same token, you don’t see the kind of support amongst Trump supporters that you might expect for the actions of the people who entered the Capitol that day. Only 25% approved in one way or another. Forty percent (40%)—and that was the plurality of Trump supporters—actually disapproved. Twenty-nine percent (29%) were kind of, “Well, I’m not quite sure what I think of it. I’m kind of in between on this.”

Only when you get to Trump populists did you get a plurality actually saying, “Yes, I approve of this.” And it was only 37%. So there is a real distinct discomfort with what happened back then based on what we see in the survey. And I think that it’s part and parcel of the threat and fear that we’re detecting in other parts of this survey—a sense that that wasn’t quite right, and it doesn’t really matter which side of the fence you’re on in terms of political alignment, you have misgivings.

For those who approved, we asked them another question. We basically said, “Why do you approve of this?” Do you think that this is something that should happen every time we have a disagreement over the outcome of the election, or do you think this was a special case?

First of all, we’re asking very few people. Some said, “Yeah, I think you do this every time [questions are raised].” And I think that would probably alarm people to hear: Look, you approve of this, and you think there should be a protest every time there’s a question? We didn’t have a coalescing around the idea that it was a special event, which means that for the people who approve, they’re not necessarily looking at this as something that shouldn’t happen again. And all of the polls that we’ve got are indicating this is going to be another close election.

So the possibility that we’re going to be debating whether or not it’s a legitimate outcome is going to be looking us square in the face all over again. A majority of Trump supporters are saying that Biden’s election was illegitimate—about 57%, I think. And yet if you go into the Harris supporters, of course, the vast majority, mid-90s, say that yes, it was a legitimate thing. One of the things I guess I found a little concerning in terms of the perceived validity of the upcoming election was the number of people who were neither Trump nor Harris supporters who kind of said, “Look, I don’t know. I just don’t know enough to say.” You’re looking at numbers that are in the 30 percents effectively saying, “I’m not sure.”

So only amongst the Harris supporters did you see a strong conviction that that was a legitimate outcome. I guess you would like to feel that if there is a declaration of the election in 2024—someone’s declared a victor—various protests would move through the courts, and it would be resolved in a way that did not involve a whole lot of people saying, “I think this is illegitimate,” with yet another march on the Capitol. Again, most people were saying they did not believe this was a good thing.

“There’s just not the kind of [strong] conviction that you would want to see if you were hoping for a quiet, peaceful, no-doubt-about-it [presidential] transition once a winner is declared.”

We did ask people who disapproved of that, “What do you think happened?” Do you think this was a coup attempt? Or do you think it was essentially a peaceful protest that got out of hand? And once again, there’s a strong political valence there. Amongst Harris supporters, 79% said that was a coup attempt. And amongst Trump supporters, only 8% thought it was a coup attempt. Fifty percent (50%) of them thought it was [initially] peaceful. But a fair number of the Trump supporters were never asked their view of the crowd. They approved what happened on Jan. 6, so we never asked them this question. And we had a number who said they weren’t sure.

So again, there’s just not the kind of conviction that you would want to see if you were hoping for a quiet, peaceful, no-doubt-about-it transition once a winner is declared. There is a slippery feel in some of these numbers that suggests that people were not foursquare behind what happened last time, and that even if in general, there’s a sense that the right thing happened in the end, it’s not the strong, bold conviction that you would expect or hope—or that you would have seen in the past, I guess, more than anything.

Landry: Thank you for listening to Zooming In, a project of The UnPopulist. For more like this, make sure to subscribe for free at theunpopulist.net. Until next time.

The UnPopulist invites interesting thinkers from across the political spectrum to foster a wide-ranging and thoughtful conversation to advance liberal values, including thinkers it may—or may not—agree with.

© The UnPopulist, 2024