Tim Walz Isn’t a Radical, He’s a ‘Neighbor’

Neighborliness is the Democratic VP nominee’s response to MAGA’s nativist and exclusionary politics

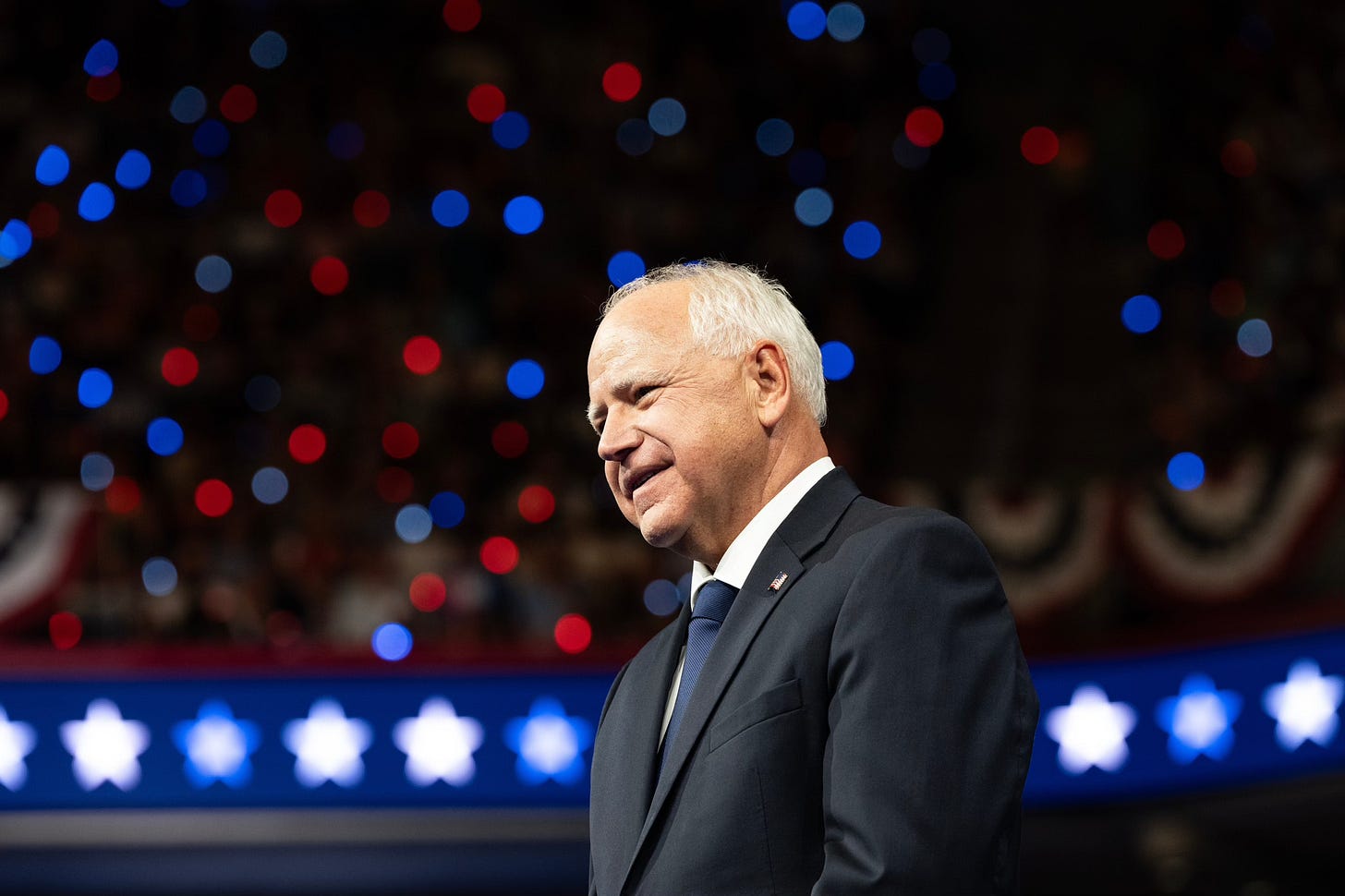

A day after Vice President Kamala Harris formally secured the Democratic nomination for president, and two and a half weeks after President Joe Biden withdrew from the race, Harris picked Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz to be her VP over two of the other finalists: Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro and Sen. Mark Kelly of Arizona. Republicans immediately saw in Harris’s pick confirmation of their long-running smear that she is a radical leftist. But while Walz is more progressive than his rivals, and is quite comfortable speaking the left’s language, he’s not really a hardliner.

Walz’s animating concern is about the importance of being a good neighbor. It organizes his political worldview. Therefore, understanding it is necessary to understand him and his commitments, both for good and ill, ahead of his vice-presidential debate with JD Vance next Tuesday.

Neighborliness as Walz’s Animating Characteristic

During a White Dudes for Harris fundraising Zoom call, Walz said, “one person’s socialism is another person’s neighborliness.” The point wasn’t to argue for the implementation of doctrinaire socialism, as his conservative critics alleged, but to emphasize that actions and policies that take our pluralism seriously often get unfairly dismissed as radical leftism. His aim was to redefine progressive politics not as a slow-moving statist takeover, as Republican portrayals suggested, but as a form of affirmative concern for your community and the people around you.

Neighborliness is one of the main victims of this era of intense polarization and digitized communication. In recent decades social trust has eroded, and other social capital indicators reinforce the same conclusion. There is an anger and cynicism about one another that runs from small town squares to urban high-rises.

However, neighborliness is not just about interpersonal decency. In Walz’s usage, it’s about social policy, which is far broader than most uses of the word; this is a neighborliness of scale. Walz is not dismissive of everyday neighborliness—on the contrary, for him it’s a microcosm of good governance. But his conception does go beyond mere interpersonal neighborliness and informs a full social vision predicated on the idea that what it means to be a good neighbor is the same as what it means to take seriously the demands of a multicultural democracy.

Neighborliness doesn’t preclude conflict. Inevitably, conflicts arise, even among neighbors. But what we need is to be able to engage with and accept one another as human beings—imperfect, difficult, often wrong, and sometimes maddening. Walz’s neighborliness relies on that notion of acceptance as a precondition for a responsible politics—the first thing to go in an era of exclusionary politics when nationalists portray a politics of acceptance as a marker of wokeism. That, ultimately, is what Walz meant by “one person’s socialism is another person’s neighborliness.” But to a movement that sees the acceptance of others as ruinous to the country, neighborliness will come across as extremism.

Walz’s reliance on the concept of neighborliness is not academic. It’s not something he arrived at by abstract theorizing. His appreciation for neighborliness stems from his own background and experiences.

The Where and Whence of Walz

Walz’s biography charts through the small towns and regional schools of the plains and upper Midwest, in contrast to either Kamala Harris’s or Donald Trump’s, both of whom were big-city kids. Unlike many of the country’s most high-profile politicians, Walz’s political story begins later in life and his pre-political résumé is full of town names and school mascots likely only known to a few people in the area. Compared to the town of a few hundred that he grew up in, Walz’s birthplace of West Point, Nebraska—population ~3,500—was practically a metropolis. Walz would eventually see a much wider world, following his college degree at Chadron State with a stint teaching English in China. He went on to build a career in education alongside decades of military service through the Army National Guard. He left the National Guard after 24 years to pursue a seat in the U.S. House. Of that decision, one of his fellow servicemembers told MPR News, “He loved the military, he loved the Guard, he loved the soldiers that he worked with, and making that decision was very tough for him.”

After serving six terms as a congressman representing a district that Rahm Emanuel initially thought too red for his cash-strapped operation to win, Walz ran and won the governorship of Minnesota. There, his record was unabashedly progressive: free school lunches, felon voting rights, paid family leave, a child tax credit, and aggressive climate action.

But Walz has framed his record as an exercise in neighborliness. This was at the heart of his DNC speech, in which he talked about “the responsibility we have to our kids, to each other” and argued that Trump and his party “don’t understand what it takes to be a good neighbor.”

Presentationally, Walz has leaned into a kind of folksy politics of affability to sell his agenda. Take, for example, when he signed free student lunches into law in Minnesota surrounded by smiling grade-school children. At that signing, Walz explained, “As a former teacher, I know that providing free breakfast and lunch for our students is one of the best investments we can make to lower costs, support Minnesota’s working families, and care for our young learners and the future of our state.”

Interestingly, Walz’s own biography also suggests how individuals and not only government action can embody neighborliness. This is exemplified in his decision to become the faculty sponsor for his high school’s gay-straight alliance in the late 1990s, after Minnesota’s own legislature had passed a law defining marriage as between a man and a woman. His critics have baselessly held up his willingness to sponsor this alliance as evidence of ulterior motives—but that’s precisely Walz’s point: being a good neighbor is not about personal gain but using our place in society to benefit those whose own level of acceptance in society falls short of our “neighborly” ideal.

Not Left or Right, but Just Across the Street

As a politician, Walz is far from perfect. Big government programs are not the only way to do right by our neighbors. They can backfire and be harmful. While Walz often articulates his progressive policies through a sense of neighborliness, one can quibble with the former without finding fault in the latter. One can maintain, for example, that Walz is right that “we have a responsibility” to craft policy that is beneficial to American children, but that doesn’t necessarily mean landing on the same policies as Walz has and developing a government program for every childhood need.

Walz’s neighborliness is a response to the overwhelming alienation in American society and an attempt to counteract that, and not just a shorthand for his particular progressive policies. After his 2018 win in the Minnesota gubernatorial contest, Walz told his local paper, the Mankato Free Press, that “I come back to the lessons of Mankato. … It’s about hard work and not being nasty, it’s about inclusion, and it’s about doing what’s best for everyone.” A former student told the paper, “He could field the most difficult question and he’d still look the questioner clear in the eye and tell them exactly what he thinks and how we as a community can move forward together.”

Neighborliness that Transcends Ideology

Neighborliness is not an inherently progressive or conservative virtue. It is instead a social virtue that animates the best politics from across the spectrum of liberal-democratic life. And in fact, Walz’s description of his own small town and its values speaks to this.

For example, when Walz evokes the way the people in his hometown of Butte came together to support each other, he is simultaneously speaking to an idea of community to which we can all easily attach our own experiences and one that is, by the numbers, weaker today than it has been for some time. We don’t only trust our institutions less than we once did—we trust each other less. In the midst of an already severe crisis of political polarization, Americans are also pulling back from their communities. Volunteerism has declined, recently hitting its lowest mark in three decades. The effects on the body politic aren’t just at the system level; they reach down to the molecular. That is to say, each of us is paying the price individually, as shown by the Surgeon General issuing a warning in 2023 about the “epidemic of loneliness and isolation” and its associated harms.

We are losing our sense not only of how to be neighbors but of who our neighbors are. This is not to dismiss the near-magical connectivity offered by modern media and telecommunications, nor to dismiss the more universal bonds of humanity. But place does matter, and the combination of declining trust, rising loneliness, and decreased volunteerism in an era when we can spend hours online raging at people hundreds or even thousands of miles away is hard to ignore. It is an odd thing that as we are tearing down barriers between people and places in the form of faster and more sophisticated digital technologies, we are putting up even stronger barriers between ourselves and people just across the street.

Neighborliness In a Global Village

The notion of neighborliness can diminish—or expand—one’s humanity, depending on whether one takes a zero-sum versus a win-win view of the world. And it is here that Walz has some thinking to do, especially about his trade-wariness.

Not so long ago, both parties put hope in a world of increasing connectivity and growing international trade. Unfortunately for both American consumers and the global economy, protectionism has been in vogue in both parties since 2016. Under Walz, Minnesota has largely been a booming economic success, with plenty of big multinational corporations playing a role. He’s worked to promote markets for Minnesota’s agricultural products, making trips to multiple East Asian countries.

But as Politico notes, Walz opposed legislation that would have enabled President Obama to more easily conclude the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement and, in his first term, voted against a free trade agreement with Peru. Walz justified his vote by noting, “We need a trade deal that’s fair, that restricts currency manipulation, promotes ‘Made in America’ manufacturing, and opens foreign markets.” This statement isn’t outrageous, but it does expose the hints of a zero-sum view of the world, a flaw in his thinking that too many Democrats and Republicans share.

The TPP was an unfortunate casualty of the 2016 election and marked the shift toward protectionism by both parties. One of Trump’s most pernicious effects has been shutting down politicians willing to champion the benefits of trade for their communities. There are few left who can make case that, when done right, free trade can help rather than hurt local communities. Protectionism is often a false promise. Throwing up barriers can neither turn back the clock of global economic history nor deliver the long-term prosperity its advocates promise to working-class and agricultural communities.

Neighborliness: The Root of Liberal Politics

Still, Walz’s work promoting student trips to China suggests an open outlook, one that grasps the importance of international cooperation to building a world of even greater peace and prosperity. And his commitment to Ukraine in its fight against Putin’s aggression conveys that he understands the role of American strength in bolstering international liberal-democratic values.

As a politician, there is probably more for progressives to like than conservatives. Indeed, conservatives, such as they are in this particular moment, will likely find plenty to dislike.

But Walz’s appeal to neighborliness is compelling, not as a defense of progressive politics but as a claim about the root of politics itself. Relationships and locale matter. Politics still has intimate foundations, shaped by our proximate relations. When these rot away, and the main forms of participation we turn to are the highly polarized fights of national partisan politics and the space-collapsing, identity-contorting experience of fighting with strangers through screens, our democracy starts withering.

Thanks to Walz’s particular brand of “neighborliness,” his policies have a progressive flavor but his persona reflects a rooted, communitarian conservatism. That combination can have downsides for a (non-progressive) liberal politics, but its fundamental decency and wholesomeness is a net plus for it. There is something to said for that over the constant rage, anger, and hatred toward vulnerable populations that his VP rival has made his signature and will likely display on the debate stage.

© The UnPopulist, 2024

If someone considers Walz a radical, they are telling on themselves.

Maybe one day people can treat word "radical" with the same eye roll some use when the word "racist" comes up.

Some people have some very disingenuous definitions of "radical" here in these comments.

Then again, they don't really know what Marxism, socialism, or liberalism are either, so they will be wasting everyone else's time with their not-worthwhile criticisms, too.

Capitalism is going to need better defenders than these folks.