The Conservative Supreme Court’s Decision Allowing Deportations to Third Countries Should Shock the Conscience of Americans

The fate that likely awaits those deported to South Sudan violates the Constitution’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment

“These barbaric criminal illegal aliens will be in South Sudan by Independence Day,” read the Department of Homeland Security’s press release on the deportation of eight undocumented immigrants to South Sudan after the Supreme Court lifted a temporary injunction barring their removal earlier this month. Of the eight, only one has any connection to South Sudan—in fact, none of the other seven have any ties to any country on the African continent. Few Americans will shed tears over the fate of these individuals, who have been convicted of murder, kidnapping, child sexual assault, robbery, and other violent crimes. But the principle at stake transcends their particular rap sheets. The U.S. government’s decision to send immigrants convicted of crimes to a country experiencing horrific conditions after being ravaged by decades of war—a country that the U.S. government itself warns Americans not to visit—is inhumane and unconstitutional, especially given what likely awaits people like them.

Americans take for granted that even if a person is convicted of a crime, he or she cannot be subjected to cruel and unusual punishment, much less torture. Nor can anyone be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process. These rights are guaranteed by the Eighth, Fifth, and 14th Amendments. They apply to all persons in the U.S.—including undocumented immigrants, as the Supreme Court has reaffirmed—not just citizens and legal residents (though there are important caveats for undocumented immigrants apprehended near the border soon after they cross).

So how is it that these eight men now find themselves, not just deported to a country they have no ties to (again, only one is South Sudanese), with little or no meaningful opportunity to legally challenge their removal, but to a country experiencing one of the most severe humanitarian crises in the world? And why would the Supreme Court so summarily lift a lower court order temporarily barring their removal, not once but twice?

Cruel and Unusual Deportation

During its first hundred years, the Supreme Court was largely silent on what constituted cruel and unusual punishment. Over time, the court provided parameters in various cases to guide legal application of the idea, including that sentences must be proportionate to the crime and cannot be excessive (Weems v. United States, 1910) and that the conditions of confinement cannot constitute torture, such as, for example, severe overcrowding that poses a serious threat to safety and health (Brown v. Plata, 2011).

The eight deportees to South Sudan had already served their time in the United States for the offenses for which they were convicted. Still, DHS transported these men to the war-torn African country to be held for an indefinite period after they had completed their sentences. Life in South Sudan is precarious for ordinary people—it is unimaginable how much harsher the conditions are for the country’s incarcerated population. For individuals with no ties to South Sudan to be deported there, even after they’ve served their time in the U.S., is an extra-legal extension of their sentences—it is an outcome that is unmistakably and gratuitously punitive in nature.

Although the U.S. government has kept secret the details of the agreement it reached with South Sudan, it is unlikely that the U.S. would have paid for these men to simply emigrate there and be let free. That means they are likely to rot in overcrowded cells, with inadequate food or medical care, and possibly will continue being held in this way for the rest of their lives. In the U.S. State Department’s most recent country report for South Sudan, it notes that its National Security Service (NSS) “maintained at least three facilities where it detained, interrogated, and sometimes tortured civilians. At least one detainee reportedly died due to injuries sustained in NSS detention.” If this is how the NSS acted toward civilians, how can we be sure that the men we’re sending there won’t face similar treatment?

Even more concerningly, this deportation-as-punishment was inflicted before the men could exercise their right to due process under the Fifth and 14th Amendments. They found out they were being sent to South Sudan just hours before they were loaded onto a plane, with no meaningful opportunity to file for relief under the International Conventions Against Torture, to which the U.S. is a signatory.

But the Supreme Court chose not to address either of these constitutional issues. Instead, the majority focused only on whether the lower court had exceeded its authority, which brought a scathing—and much deserved—rebuke from Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

No Safety in South Sudan

The men were originally bound for South Sudan in May when a district court judge temporarily enjoined their removal. They ended up stranded along with their DHS guards in Djibouti, a country on Africa’s northeastern coast, held in a storage container on a U.S. military base for six weeks. (During that time, U.S. personnel cited concerns over malaria, other unknown respiratory illnesses, triple digit temperatures, smog clouds that made it difficult to breathe, and rocket attacks from terrorists—a potential preview of what awaited the deported men in South Sudan.)

On July 3, the Supreme Court handed down its final order vacating the lower court’s preliminary injunction and paving the way for their removal to South Sudan—due process, to determine whether this violates U.S. and international law barring torture, be damned. As the aforementioned press statement gleefully predicted, the prisoners were on the ground in Juba, the South Sudanese capital, one day later.

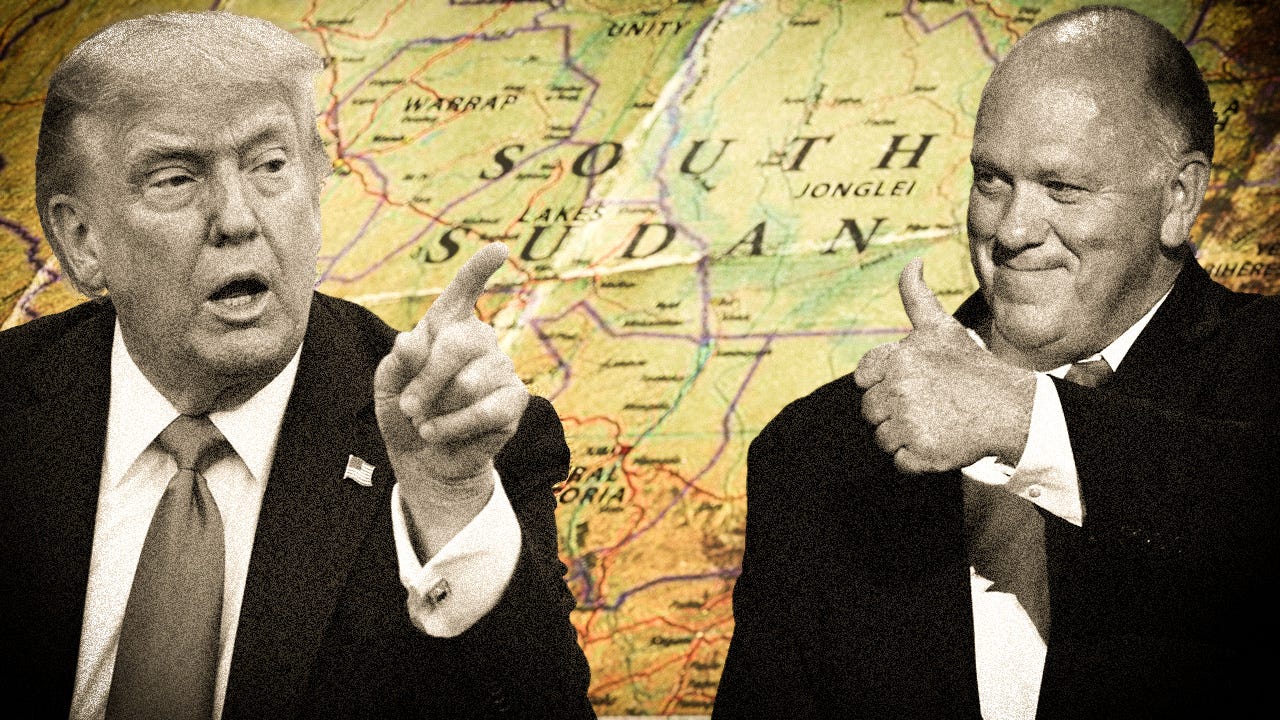

We have no way of knowing what will happen to these men now. The Trump administration claims it received assurances that they would not be tortured. But it has not disclosed what provisions it has taken, if any, to ensure that South Sudan’s government makes good on those assurances. U.S. border czar Tom Homan told Politico last week that once the U.S. deports an individual to a place like South Sudan, it doesn’t track their ongoing status or even what country they’ll be in a week later.

But let’s assume that the men are freed by the South Sudanese government and allowed to move on with their lives. Homan’s admission still flies in the face of the U.S.’s constitutional prerogative to ensure it is not subjecting anyone—immigrants included—to cruel and unusual punishment, since South Sudan is exceedingly dangerous whether you’re a prisoner or free.

South Sudan, which was ravaged by civil war from 2013 to 2020, is on the verge of sliding back into a full-blown internal war once again. According to the United Nations Refugee Agency, nearly two million people are displaced in South Sudan, most of them women and children, with widespread hunger, endemic flooding, and disease making normal life there impossible. In the last three months, more than 165,000 people have fled the country. Under such conditions, who can possibly guarantee the safety of the men the U.S. has sent there, much less their humane treatment? Where will they be incarcerated—and on what grounds? How much is the U.S. government paying to keep these men locked up, and for how long? One can easily imagine them forced into slavery, a practice common in the region. According to the U.N. Mission in South Sudan, 54 people—including one child—were extrajudicially executed in the first 10 months of 2024. Could the men we’ve condemned to life in South Sudan end up dead?

Supreme Injustice

The Supreme Court’s conservative majority appears unconcerned about these questions. Its two rulings on June 23 and July 3 dealt only with the question of whether a district court judge exceeded his authority in issuing a preliminary stay of their removal and whether the judge followed the court’s order when it lifted the stay, respectively. These issues are not unimportant—and one could argue that a lower court’s failure to follow a ruling handed down by the Supreme Court is a serious breach that must be corrected. But given the stakes—affecting not just these eight men but perhaps thousands more at risk of being deported to dangerous third-party countries—why couldn’t the court have allowed the underlying cases to reach them in due course before rebuking the district court judge?

I understand the conservative justices’ preference for addressing only the immediate issue before them, which was not the constitutionality of the government’s actions, but rather a petition by the government to stay the orders barring the men’s removal. But this case screams out for some balancing of the equities involved. The Supreme Court could have left the injunction in place while the case moved forward, which would have meant a temporary delay in removing the detainees to South Sudan but would have kept them in U.S. custody. Such a plan would have incurred costs, but not more than transporting them by private charter halfway across the world and paying another country to receive them. More importantly, this course of action would have preserved the Fifth, Eighth, and 14th Amendment claims to which these men were entitled. Instead, the Court has jeopardized these men’s lives.

Again, it’s hard to sympathize with someone convicted of “lascivious acts with a child under 12” or first-degree murder during a robbery. But Americans commit those crimes, too—and for the same reason that it’s never appropriate to suspend adherence to the Constitution in order to respond to those crimes, neither is it appropriate to do so in the case of immigrants. The court’s decision opens the way for countless others to be sent to dangerous, lawless places, even those whose only offense was crossing the border without authorization, some as children.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio has been in discussions with dozens of countries to accept deportees, including Libya, Rwanda, and Ukraine, the latter representing the most stable destination from the perspective of human rights ... if the country weren’t in the midst of a devastating war with Russia. Just yesterday, the Associated Press reported that the Trump administration deported five immigrant men to Eswatini, Africa’s only absolute monarchy, who will be held in solitary confinement for an indefinite period of time. These acts should shock the conscience of anyone who believes in America’s essential goodness. The court’s conservative majority narrowly focused on a minor case of judicial overreach but in the process shattered Lady Justice.

© The UnPopulist, 2025

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

One institutional and structural reason for the current international system of deportations is that there is no official global citizenship, thereby resulting in national governments being able to act in inhumane, arbitrary and discriminatory ways instead of fully respecting individual rights and freedoms and cooperating in accordance with the rule of law. Arbitrary depictions are a way for authoritarians to provide mental masturbation for their voters by triggering tribalist and authoritarian actions in the heads and brains of their voters who are feeling stimulated by such actions of governments

The Supreme Court has long been rather hostile to the 8th Amendment ban on cruel & unusual punishment, even for American citizens. For example, the Supreme Court upheld a life sentence (if I remember right, without parole) for first time possession of 6 grams of cocaine, and another guy for stealing a $50 TV (with possibility of parole).