Politics Sometimes Needs Great Literature to Save It from Itself

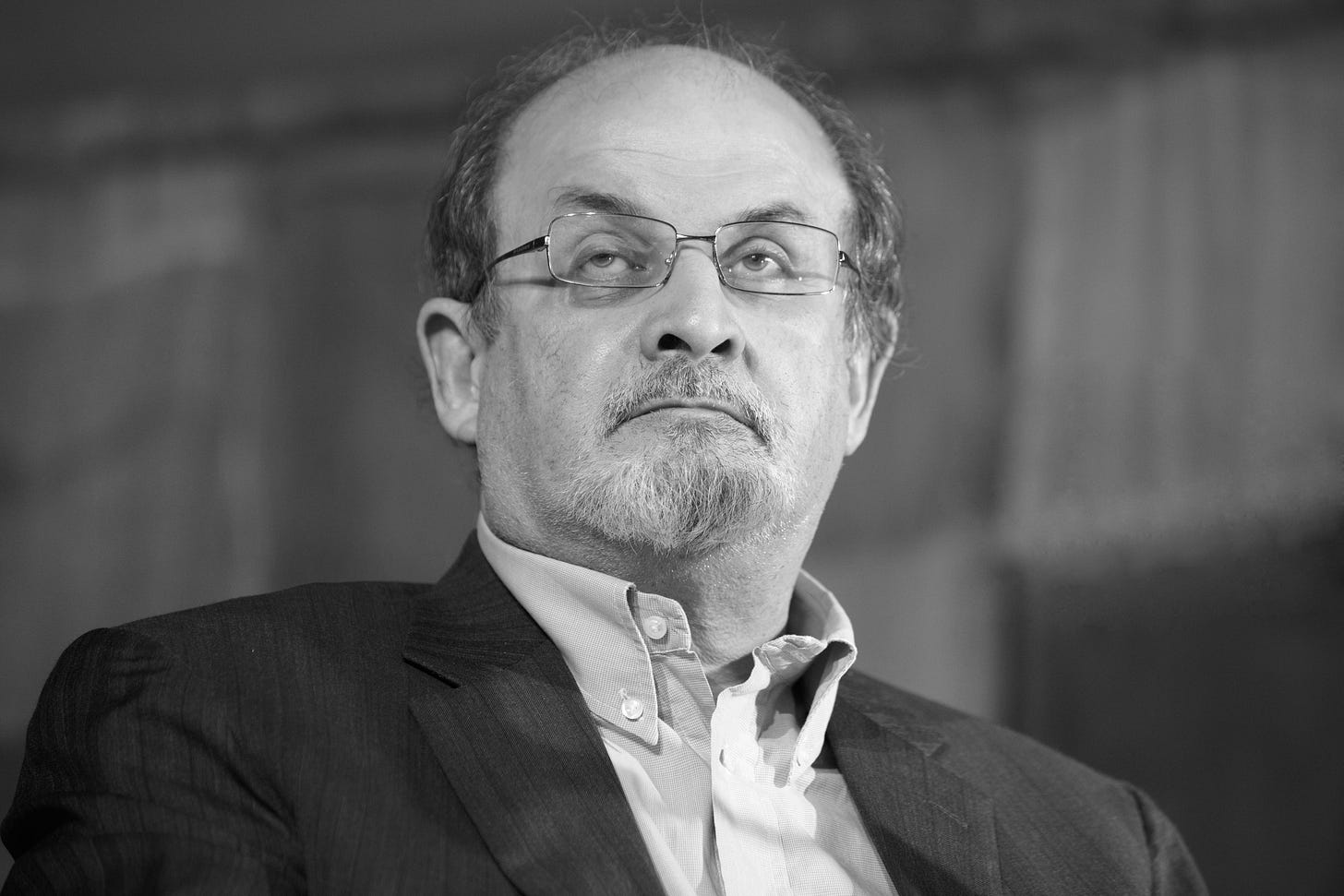

Salman Rushdie's Victory City, an allegory of our current struggle for liberalism, rises to the occasion

Book Review

Salman Rushdie’s latest novel, Victory City, stands as a testament to its author’s undiminished faith in the power of storytelling to shape individual human lives and societies alike. It’s a kaleidoscopic magical realist fable that’s a pleasure to read, an epic yet brisk tale that holds myriad potential meanings in its passages. An omniscient narrator, “neither a scholar nor a poet but merely a spinner of yarns,” relates the rise and fall of a medieval Indian empire as written in verse by an ageless woman inhabited by the local incarnation of a Hindu goddess—albeit “in plainer language” than the original Sanskrit.

At heart, Victory City is a meditation on the broader spiritual and philosophical struggles between fanaticism and freedom, intolerance and liberality that take place in every human society—and how the stories societies tell themselves help define who and what they are. These stories and struggles don’t always have happy endings; successes are always impermanent, always under threat from the forces of reaction and their own inexorable entropy. As Rushdie has an itinerant Portuguese traveler put it midway through the novel, “the truth about these so-called golden ages is that they never last very long. A few years, maybe. There’s always trouble ahead.”

To be sure, Rushdie does not shy away from offering commentaries on contemporary politics in various passages and plot points in Victory City. At a number of points across the narrative, it’s not hard to hear echoes of present-day politics: India’s dark turn to illiberalism and prejudice under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, for instance, or stand-ins for the geriatric theocrats that have ruled Iran for more than four decades. Obvious as these specific allegories may be in the narrative, they feel natural and lend the novel a verisimilitude that more forced and clumsy political critiques in works of fiction all too often lack.

But Rushdie’s ambitions aim much higher than mere commentary on current events. He’s far more concerned with the way the stories we tell ourselves, and how certain narratives can bring out the best in ourselves—while others not only bring out the worst in ourselves but demand all other stories be censored or expunged. It’s here where Victory City leaves a lasting impression, with a master storyteller showing us that nations and societies are ultimately founded on that most powerful of human creations: the story.

Rushdie’s fictional empire of Bisnaga arises from nothing, with the novel’s divinely inhabited protagonist Pampa Kampana giving its founders magical seeds from which a city and its inhabitants sprout over the course of an afternoon. Pampa Kampana then “whispers” to these newborn individuals, imbuing the empire’s citizenry with personal and collective histories. Through these stories, Rushdie writes, the city’s population:

became human beings, even if the stories in their heads were fictions. Fictions could be as powerful as histories, revealing the new people to themselves, allowing them to understand their own natures and the natures of those around them, and making them real. This was the paradox of the whispered stories: they were no more than make-believe but they created the truth, and brought into being a city and an army with all the rich diversity of nonfictional people with deep roots in the actually existing world.

It's impossible to read passages like this—Rushdie scatters many of them throughout the novel—and not imagine the ways actually existing nations constantly tell stories about themselves. That’s as true for long-established nations like the United States as for more recently independent ones like Rushdie’s native India, all of them needing to create and renew shared stories, however fictional or imaginary, about their shared past, present, and future.

But as Rushdie remains keenly aware, just about anyone can tell a story about a nation or a society. Pampa Kampana’s efforts to promote a liberal and tolerant Bisnaga regularly run into opposition from the very people she quite literally created. She repeatedly engineers golden ages marked by cultural flowering and female emancipation—women “are neither veiled nor hidden” in Bisnaga, she proudly asserts—only to see them give way to religious reaction and fanaticism after a period of slow decay. As Rushdie’s narrator observes, “Once you had created your characters, you had to be bound by their choices. You were no longer free to remake them according to your own desires. They were what they were and they would do what they would do.”

After Pampa Kampana’s first exile, Bisnaga’s new religious despots proclaim that they will tolerate just one narrative from now on – their own. A Khomeini-like figure named Vidyasagar influences the new regime, which sets up a “governing body of saints” akin to Iran’s theocracy to enforce their own dictates across the city and empire. The new powers-that-be want “to change the names of all the streets, to get rid of the old names and replace them with long titles of various obscure saints, so now nobody is sure where anything is anymore, and even long-time residents of the city are obliged to scratch their heads when they need to find an address.”

When Pampa Kampana returns to Bisnaga to foment political change, she finds that her whispers aren’t as effective as they once were. Generations after its founding, the city’s citizens are no longer “pliable fictions,” and the city’s population had itself expanded substantially. “Now there was a multitude to address,” Rushdie’s narrator tells us, “and this time [Pampa] would have to persuade them that the cultured, inclusive, sophisticated narrative of Bisnaga that she was offering them was a better one than the narrow, exclusionary, and, to her way of thinking, barbarian official narrative of the moment.”

It wasn’t an easy task; religious intolerance and illiberalism “had a certain infectious clarity,” while many fence-sitters would choose not to rock the boat so long as the empire remained prosperous. Ultimately, though, Rushdie’s narrator remarks that “it was as if cadavers were in charge of things, the dead ruling the living, and the living were tired of it.” Change came when Pampa Kampana whispered in the ears of the ruling monarch, causing him to shift his views and policies while convincing him they were all his own idea. In the face of popular protest for “poetry, liberty, women, and joy,” the old regime then “crumbled in days and blew away like dust, revealing that it had rotted from the inside.”

Bisnaga goes through one more cycle of rise and decay before falling for the last time. This time, though, the people of the city whisper to Pampa Kampana rather than the other way around. The final verses of Victory City’s fictional epic poem, Rushdie’s narrator notes, “gave voice to the anonymous, the ordinary citizens, the little people, the unseen, and many scholars assert that in these pages of the immense work Bisnaga comes most vividly to life.”

With Victory City, Rushdie reminds us of the indispensable role stories play in our shared national lives—and does so with considerable assuredness. There’s more to the novel than that, of course. Rushdie celebrates the syncretic mingling of cultures and peoples throughout the book, for instance, whether it’s a Portuguese merchant bestowing the name Bisnaga upon the city through a mispronunciation or the simple reality that the empire itself is populated by adherents of multiple faiths and none at all.

But that’s precisely Rushdie’s point: it matters enormously what stories we choose to tell ourselves as societies and as nations. We can understand ourselves in broad-minded, generous ways that don’t necessarily exclude other narratives—or we can do so in narrow-minded, intolerant terms that impose a certain understanding from the commanding heights of society on down, whether its through the media, laws, schools, or bureaucracy. It’s up to those of us around the world who believe in truly liberal and open-minded societies to tell compelling stories for our fellow citizens, not cede ground to illiberal voices on both right and left who insist they’ve found the one true narrative that defines our countries.

As the final words of Victory City insist, “Words are the only victors.”

An earlier version of this review was originally published in Liberal Patriot.

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

We welcome your reactions and replies. Please adhere to our comments policy.

Thank you for this. I'm saddened by the current emphasis on having more people trained in STEM in the population, either through education or through immigration. That means that we want more stuff. I think we have plenty of stuff already. I'm for more people trained in the humanities. Maybe I'm the only one.