Will Canada Continue to Resist the Populist Tide?

It harbors both pro and anti-liberal democratic forces and it is hard to say which side will win

As illiberal populism with its nationalism, xenophobia and disrespect for democratic norms surges around the world, Canada has withstood the tide reasonably well. But does Canada have special resilience against this brand of populism? Not really. Some political forces in Canada may help to hold off a populist wave, but others make it vulnerable.

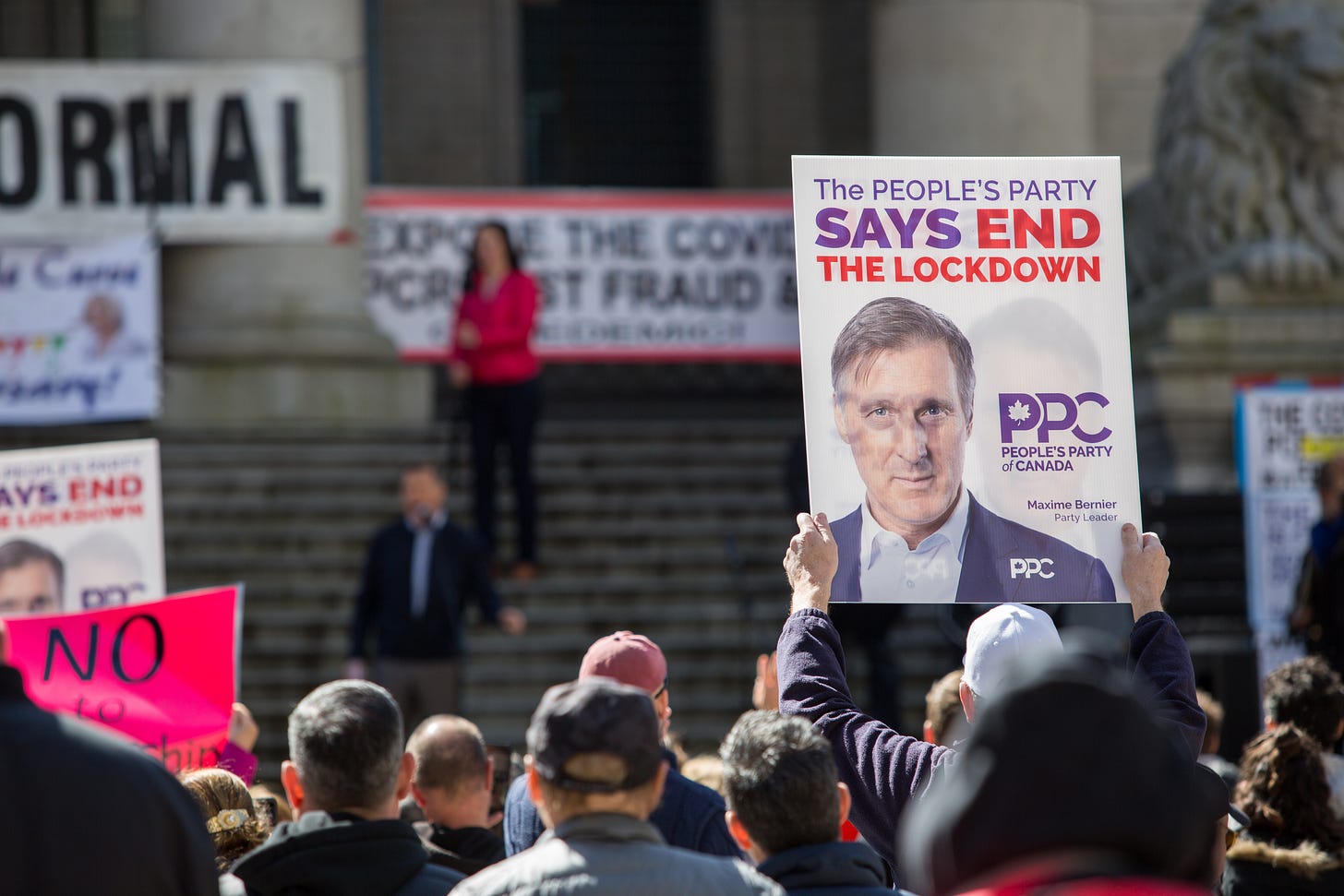

Among the reasons to hope that Canada can keep beating back the tide are the fact that Maxime Bernier of the right-populist, anti-immigrant, COVID-skeptical People’s Party of Canada failed to win any seats in Parliament in either the 2019 or 2021 elections. Meanwhile, Doug Ford, the Progressive Conservative premier of Ontario—and brother of internet-famous mayor Rob Ford—who had strong populist vibes when he swept to power in 2018, has moderated dramatically. He ran on policies for “ordinary people” over the “insiders” and “political elites.” But then he became possibly the most pragmatic conservative party leader in the country, treating Liberal Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, for example, not as an elitist enemy but an opponent with whom he could nevertheless collaborate to get things done.

But there are also reasons to worry that illiberal populism may not pass Canada over. In a February poll, a whopping 67% of Canadians, confronting rising health care and housing costs, said they felt like “everything is broken.” They are losing trust in existing institutions, and voters across the political spectrum increasingly feel that ordinary politics is unable to solve problems. This might well make strongman politics more attractive, including greater sympathy for the use of the Emergencies Act or circumventing parliamentary scrutiny.

Such feelings of political impotence could also invite attempts to find a political “other” to blame. In 2019, even before the pandemic, a quarter of Canadians hated their political opponents—fertile ground for us-versus-them politics.

Moreover, notwithstanding Bernier’s lackluster electoral performance, populist victories are beginning to pop up: Danielle Smith, who is right-populist, COVID-skeptical and pro-Western sovereignty, was elected premier of Alberta last October. So far she has not moderated as dramatically as Ford—although she has dropped some of her most controversial promises like pursuing Cabinet power to bypass legislative oversight.

Federal politics is also tipping its hat to illiberal populism. Pierre Poilievre, the leader of Canada’s Conservative Party, is a populist conservative who caters to grievance politics and conspiratorial thinking, plays up culture war issues, and attacks traditional gatekeepers like the legacy media. Meanwhile, Trudeau has been drawing from the populist playbook out of political opportunism—politicizing the pandemic and Canada’s vaccination campaign with an early election, casting his political opponents as un-Canadian, and emphasizing culture war issues and messaging rather than substantive policy reforms.

While the kind of illiberal populism on the rise around the world remains (for now) more of an influence on the style rather than the substance of Canadian politics, populism in various forms has been important throughout Canada’s history—at both the federal and provincial levels.

Populism in Canada can be defined both in the more familiar sense of a political ideology representing “real people” in opposition to a “political elite” or “other” and also as a type of political party that emerges through a popular uprising and demands regional representation. Provincial populist candidates consider Ottawa and the rest of Canada the “other.” Because of the importance of this latter form of populism in helping secure stronger regional representation, it’s not uncommon to see Canadians across the political spectrum bristle at suggestions that populism is dangerous.

Vox Populi: Federal and Provincial

At the federal level, the 1930s Social Credit Party, which melded an ideology of agrarian populism, Christian social conservatism, and anti-communism with antisemitic tendencies, held sway for three decades. As its name suggests, it was motivated by social credit theory, which believed in addressing differences in purchasing power by handing debt-free money to consumers along with producers who sold goods below cost—and market socialism.

The Social Credit Party declined with the ascension of the Reform Party, which combined a kind of Reaganite fiscal and social conservatism with a populist desire to impose a single Canadian identity on the country and protect it with more restrictive immigration policy. It was hostile to multiculturalism and opposed any accommodation of regional identities, especially Quebécois. The Reform Party became the official opposition and displaced the Progressive Conservatives as the most politically successful right-wing federal party in the 1990s.

At the provincial level, populism has a strong and longstanding foothold in Western Canada and Québec. This may have something to do with the strong regional identities of Western Canadians and the Québécois (both nurse separatist sentiments), but also because of populism’s role in the political history of Canadian federalism.

Western Canada, in addition to siring the right-wing Social Credit movement, also spawned the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, the early 20th-century precursor to today's left-wing New Democratic Party. The CCF arose from the Social Credit League, but the party was democratic socialist and agrarian populist, opposing capitalist elites and bringing Tommy Douglas, the politician responsible for Canadian Medicare, to power in Saskatchewan for 20 years.

In Eastern Canada, the grassroots Maritime Rights Movement pushed for stronger regional representation in the federal government when the Atlantic provinces felt they were getting a raw deal from Ottawa. Québec also had a wing of the Social Credit Party that outlasted its Western cousins as a successful political force.

Quebec’s Identity Populism

But Québec is also home to more recognizably right-wing illiberal populism, bolstered by nationalism and the sense that Québécois identity is under attack. Federalism is strong in Canada generally, but Québec politics are disproportionately influential on federal politics, both because of the strength of the Québec separatist movement and the political brokerage needed since confederation in 1867 to include French Canadians.

The Québec government has targeted English Canadian and immigrant populations as threats to French Canadian national identity. In addition to a language law that severely limits non-French-speaking immigrants from being served in their own languages, Québec passed a state “secularism” law that disproportionately affects Jewish, Muslim, and Sikh communities by prohibiting religious attire like kippahs, headscarves, and turbans for public servants. While Canada has ramped up its immigration targets, Québec has cut immigration. The Conservative Party does its culture warring mainly in French, railing against irregular border crossings, foreigners and “woke culture” on French media. This strategy serves the dual purpose of reaching its core French supporters and eluding English-speaking opponents.

Policies Fueling the Populist Backlash

Beyond Québec’s politics, Canada’s housing crisis might be a particular vulnerability because of the popularity of policies targeting foreign buyers as scapegoats. The tension between admitting more immigrants to maintain population growth and fund core social welfare programs, on the one hand, and Canada’s lack of readiness to absorb population growth without, for example, triggering housing inflation, on the other, could well open up cracks for populist politics to emerge.

There is widespread resentment in Western Canada toward Ottawa’s energy policy. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau (Justin Trudeau’s father) in the 1980s implemented the National Energy Program, which sought to make the country less vulnerable to oil price shocks by replacing foreign oil with domestic sources. This seems like it could have been a boon to Western Canada given its massive oil industry. But the program came to be seen as an effort to enrich Ontario and Québec at the expense of oil-producing Western provinces because it also imposed price controls on oil.

The lingering suspicion against Ottawa since then provides fertile ground for right-wing culture warring on climate policy, with Conservatives pushing the idea that the Trudeau Liberals have undermined the Canadian economy (and the West in particular) to appease global climate activist “elites.”

The Long Reach of America’s Right-Wing Media

Finally, the volatile political situation in the United States and the American media environment puts Canada at risk. U.S. media, thanks to its sheer size and proximity, has deep penetration in Canada; most Canadians patronize U.S. social media, cable news and talk radio. This U.S.-heavy media diet has even confused Canadians about how their system of politics and government is supposed to work. Alberta’s Danielle Smith even developed a mistaken understanding of a premier’s powers, believing that as premier she would have pardon powers akin to those of the U.S. presidency.

Anti-Populist Forces in Canada

But Canada also has forces that can resist and even counter illiberal populism—chief among them being the lack of a strong, agreed-upon identity that could form the basis of a nationalism-driven movement. Canada boasts regional and other hyphenated identities that are not seen as less than simply “Canadian.” People are Indigenous, Maritimers, Québécois, Western or any number of ethnic Canadians—Lebanese-Canadians, or Chinese-Canadians, for example. It’s really only Ontarians, it's commonly said, who think of themselves as Canadian-first.

While Canada has a history of populist politics, it also has a proven history of turning radical populist movements into more traditional brokerage parties, which, unlike populist parties that focus on the representation of a specific “people,” balance the interests of different factions to form winning coalitions within Canadian democracy. The Social Credit movement, Reform Party and Co-Operative Commonwealth Federation were all integrated into ordinary Canadian politics and never felt the need to overturn Canadian democracy’s overall governing system. (The Bloc Québécois are a notable exception.)

Furthermore, Canada’s embrace of multiculturalism as official policy hasn’t led to the kind of culture wars the United States is experiencing because it is based in demographic realities. Immigration has been the main driver of population growth since 1995 and is responsible for Canada’s population reaching 40 million this summer. Almost a quarter of the country is foreign-born and more than 40% of residents are either first- or second-generation Canadians. This diversity of immigrants and popular acceptance of the need for immigration undermines xenophobia and offers a natural barrier to white nationalist forces trying to make their way across the border from America. It also makes Canadians more friendly to multiculturalism as a shared value.

And just as Canada’s need for immigration gives it a natural resistance to xenophobia and white nationalism, likewise, when it comes to trade policy, Canada isn’t equipped, thanks to its climate, geography, and population, to go it alone. Simply put, Canada is dependent on the rest of the world for goods and people and can’t afford to get a full-blown case of isolationism and protectionism—despite recent calls for a new industrial policy that would diminish Canada’s reliance on foreign supply chains.

The Future of Populism in Canada

It’s not obvious how all of this will play out, or why it hasn’t gone differently. Regional identities aren’t foolproof protection against illiberal populism—four countries with distinct national identities in the U.K. hasn’t doomed illiberal populism there. And, after all, populist sentiment is most abundant in parts of the country with identities strong enough to harbor separatist sympathies (Québec and Western Canada). Notwithstanding Canada’s dependence on trade, its close ties with the United States, a country that is big enough to be more self-sufficient, could provide an avenue for Canada to become much more insular as a part of a North American bloc.

It’s also anyone’s guess what will happen following a change in government. Pierre Poilievre, the most likely next prime minister, offers plenty of reasons to worry. But he has made few concrete policy promises, and his political career has been long and opportunistic. We have no idea what a Poilievre government would look like. It is possible that it would deliver on right-wing grievance politics by attacking legacy institutions and reversing course on immigration, protection for 2SLGBTQ+ rights and multiculturalism under the umbrella of “anti-wokeism.” But it is also possible that, like Doug Ford, Poilievre would transition to more conventional governance once in power.

Canadians need only look around the world to see that the liberal democratic consensus that made Canada one of the most free and prosperous countries is not something to be taken for granted. We’ve been lucky. But we might not always be.

© The UnPopulist 2023

Follow The UnPopulist on Twitter (@UnPopulistMag), Facebook (The UnPopulist) and Threads (@UnPopulistMag).

Very interesting summary about Canada. But also sad to read about the current situation. Many people in politics I know in Sweden often see Canada as an inspiration where everything is good and well-functioning. This is one more example of how much damage and divisions populism is creating.

Maybe I have not kept up but is it fair to characterize Mad Max as illiberal? Maybe in some ways, but fundamentally?