The Faithless Are the More Reliable Liberals

Enlightenment rationalists who rejected revealed dogma in favor of scientific inquiry paved the way for open, tolerant societies

The UnPopulist has published a series of articles on how political liberalism is compatible with and supported by the world’s major religious traditions: Protestants, Catholics, Jews, Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists. With such solid support from every major faith, you would think liberalism ought to be winning hands-down.

But what about us unbelievers? What about atheists?

We had better hope that atheism offers support for liberalism, because it is a growing share of the country’s population. In a recent poll, those who describe their religious belief as “nothing in particular” are now the largest religious group in America—28% of the population—outnumbering Evangelical Christians (24%) and Catholics (23%). About half of them are outright atheists and agnostics, who have grown from less than 5% of the population just a few decades ago, to as much as 12% today. If 12% doesn’t seem like much, remember that this is about half the figure for Evangelical Christians. And the proportion of unbelievers is much larger among the young. By some projections, America could no longer be majority Christian by the middle of this century.

These poll numbers jibe with my own personal experience. As a teenager in the Midwest in the 1980s, if you told people you didn’t believe in God, they looked at you like you were a freak who wanted to bite the head off a live bat. (Actually, that was Ozzy—who as rumor has it is a member of the Church of England.) Today, it elicits hardly a shrug. It has become unexceptional and mainstream.

There is an old argument that atheism is incompatible with a free society because the core ideas of liberalism—such as the dignity of the individual soul—are grounded in religion. So without faith, in this view, we enter a brave new world in which the state is our only God.

These fears are not well-grounded. Western Europe is ahead of America in its drift toward secularism, yet it has not promptly lapsed into dictatorship and with its support for Ukraine is arguably more solid in its defense of liberalism right now than we are—certainly more than America’s religious right.

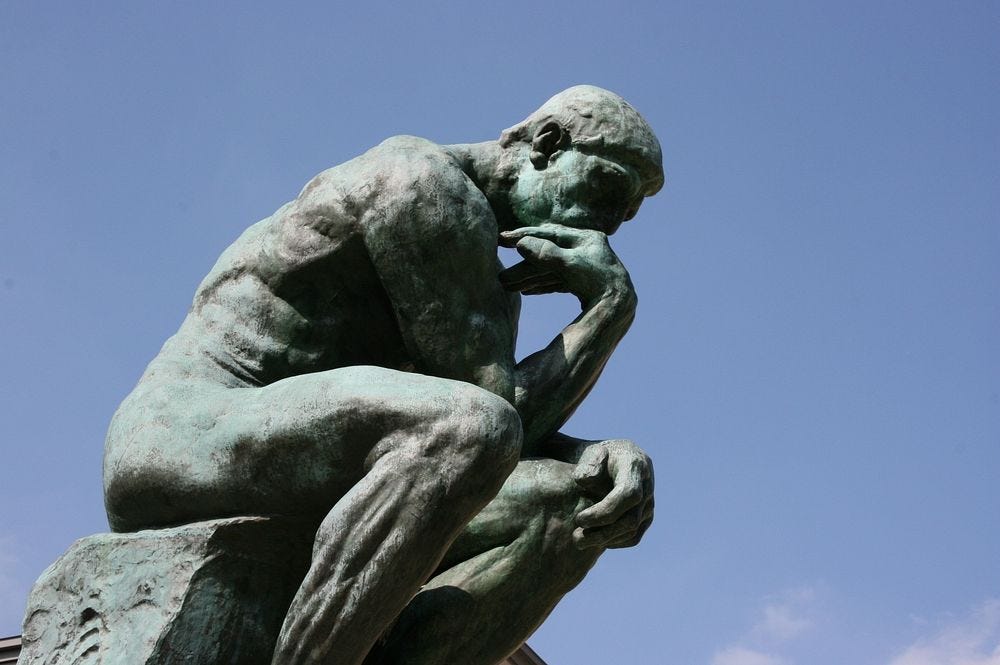

More deeply, support for liberalism can be found in both the history and the underlying philosophy of atheism. A secular worldview is not just an intellectual support for liberalism but can also be a spiritual support—a view of life and an ethos that values the free-thinking, autonomous individual.

The Half-Way House to Atheism

Historically, it may seem difficult to root liberalism in atheism, because modern liberalism developed in the 17th and 18th centuries in a predominantly Christian society. But the argument for a purely Christian origin for liberalism has a conspicuous gap in it. In Jonah Goldberg’s Suicide of the West, for example, he is forced to acknowledge that “Christianity’s emphasis on human dignity and equality did not destroy monarchy, aristocracy, and serfdom, or slavery for more than 16 centuries. But the fuse, one could argue, was lit.” Given such a large chronological gap, it is far more plausible that something else—some other set of ideas—was introduced that helped give birth to liberalism.

Liberalism’s rise actually coincides with the Enlightenment’s confidence in the power of “unaided reason,” which produced a version of Christianity transformed by secular philosophy. The impact of these Enlightenment ideas on the birth of liberalism can be seen, for example, in the career of Boston preacher Jonathan Mayhew, who was active in the middle of the 18th century and influenced some of America’s Founding Fathers. Mayhew preached “the right and duty of private judgment” and held that religious and moral questions should be subject to the examination of reason. In his notebooks, he quoted the earlier English writer Richard Steele: “Whatsoever this faculty [of reason] does naturally, and in its due exercise dictates to us, is as much the voice of God as any revelation.”

Mayhew applied this to morality:

[I]t being proposed, that there is some particular course or method of acting, which tends to promote our happiness upon the whole; and that a contrary conduct tends to our misery …, a fitness of the former course of action, in opposition to the latter, necessarily follows. … Virtue, then, is what we are under obligation to practice, without the consideration of the being of a God, or of a future state [after death], barely from its apparent tendency to make mankind happy at present.

His ethics was based on the individual pursuit of happiness guided by principles derived from reason and observation. It is a sort of halfway house to a purely secular outlook.

This influence persisted long enough to be observed decades later by Alexis de Tocqueville. Writing about “the philosophical approach of the Americans,” Tocqueville observed that “in most mental operations each American relies on individual effort and judgment” and hence “they have little faith in anything extraordinary and an almost invincible distaste for the supernatural.”

But didn’t Tocqueville write about the importance of religion for the Americans? Yes, but it is clearly recognizable as the same Enlightenment creed Mayhew had preached.

Not only do the Americans practice their religion out of self-interest, but they often even place in this world the interest which they have in practicing it. Priests in the Middle Ages spoke of nothing but the other life; they hardly took any trouble to prove that a sincere Christian might be happy here below. But preachers in America are continually coming down to earth. Indeed, they find it difficult to take their eyes off it. … [I]t is often difficult to be sure when listening to them whether the main object of religion is to procure eternal felicity in the next world or prosperity in this.

On a spectrum that runs from Augustine to Ayn Rand, the thinkers of the Enlightenment were moving closer toward the Ayn Rand end. They were nominally religious, but in terms of philosophical essentials, they were laying the foundations for unbelief.

Let’s take a look at those philosophical essentials and how they support political liberalism.

The Right and Duty of Private Judgment

Atheism as such is not a belief, but the absence of a belief, so it can include some illiberal philosophies (including a Nietzschean outlook currently popular among some Silicon Valley reactionaries). Yet in an increasingly secular world, God is mostly being driven out by the acceptance of key ideas that are essential to the defense of a free society. The first of these is the defining value of the Enlightenment: reason.

Every religion contains some element of faith and the supernatural, whereas the rise of atheism correlates with the increased acceptance of a scientific worldview oriented toward the discovery of natural laws based on observation. Such a scientific worldview has proven able to offer far more thorough explanations of the world, including the nature of the universe and the origins of mankind, than religious mythology. Evidence and reasoning have demonstrated that their power can be brought to bear on big questions—including questions of morality.

That is precisely what the growing population of “nothing in particulars” believe. When asked how they make moral decisions in the absence of religious belief, their main answers are: the desire to avoid hurting others, and “logic and reason.” The two answers are connected. As Voltaire observed (more or less, by way of a somewhat free translation), when we believe absurdities, we will commit atrocities. Most of the cruelties and terror that men have inflicted upon one another have been in the service of dogmas and fanaticism. Carefully cultivated delusions, believed in blindly, are what enable men to suppress their awareness of the fellow humanity of their victims.

There is a direct connection between the naturalist worldview of atheism, its reliance on observation and reasoning, and political freedom. To value reason is to value the process of reasoning. In a universe without supernatural revelation, no one arrives at the truth instantaneously—or infallibly. All knowledge requires a process of inquiry, deliberation, rigorous questioning and debate, and above all a free flow of information. To value reason requires that you value the freedom to engage in this process.

Historically, this was the basis for the first and most powerful arguments in favor of political freedom, freedom of conscience, and freedom of speech. In his Letter Concerning Toleration, John Locke—the philosophical giant of liberalism—rested his argument on precisely this issue of protecting the process of thinking, because “it is only light and evidence that can work a change in men’s opinions.”

Authoritarianism is always built on authority, the view that one person or institution or faction is endowed with truths that are beyond question. A deliberative democracy is built on deliberation. Atheism supports such a society by affirming that we cannot reach the truth any other way.

The Dark Side of Atheism

The obvious objection to this is that one of the great totalitarian movements of the 20th century, Soviet-style Communism, was not merely atheistic but sought to stamp out religion by force. Yet despite some of their loud rhetoric, the Communists did not do this in the service of reason or science. They did it in the service of a new dogma.

Communism was yet another authority-based system, just with a different rationalization for authority. Marx originated the idea of the “base” and the “superstructure.” The power struggle between classes is a society’s true “base,” he explained, while art, culture, and ideas are a “superstructure” sitting on top of it—mere products of the underlying power struggle that serve to legitimize one class’s dominance. Disagreement is not part of a process of cognition, it is a political attack launched by an opposing faction. (You can see the echoes of this approach in what we used to call—drawing on terminology from Marxist movements—“political correctness.”) In this view, all thinking is propaganda.

In effect, Communists rejected the metaphysics of religion but kept the epistemology of faith. All the answers are already known and handed down from some existing authority, and it is a sin to doubt. It’s just that instead of believing all important truths were announced by Bronze Age prophets, the Communists held that they were announced at the last Party Congress.

History demonstrates that this was antithetical to the conduct of actual science. Trofim Lysenko’s crackpot theories, for example, were imposed by the state and sabotaged Soviet biology and agriculture for decades. The great physicist Andrei Sakharov was forced to become a dissident in part for arguing that Soviet science required greater freedom of thought.

It is no surprise that in a secular era, the Communists would try to borrow from the intellectual authority of science, incorporate that into their rhetoric, and put it into the sales brochure, so to speak. But what the Marxists actually offered was not an alternative to religious dogmatism—just a competitor.

The Pursuit of Happiness

This leads us to the other issue that is essential to an atheist defense of liberalism: a belief in life on this earth, and particularly the life and happiness of the individual. A naturalist worldview implies not just humanism, but individualism.

All authoritarian systems are built on the idea that there is some higher purpose that takes precedence over your own life and goals, justifying the supervening coercion of church and state. But in a godless worldview, this makes no sense. Our individual lives and our enjoyment of them are the highest purpose, by virtue of being the only purposes. We are not a means to some cosmic end, but ends in ourselves, worthy of respect and protection.

This also implies that choices made by other people to believe or act differently from us have no grand metaphysical significance. If some people are making the wrong decisions, they might suffer the personal consequences of these mistakes; but it is not an affront to some divine order or a threat to the relationship between humanity and its creator. If we adopt this perspective, it is much easier to regard other people’s business as theirs—and to remember to mind our own business.

In short, liberalism is grounded in the idea that one must be allowed to choose one's own path simply because it is one's own.

The individual’s right to the pursuit of happiness is not the same as philosophical materialism, which denies the significance of consciousness and of the psychological and cultural dimensions of human life. In fact, our basic biological capacity includes the fact that we have complex minds capable of thinking and dealing with abstract ideas, forming a worldview, making emotional attachments, and seeking companionship. You don’t have to believe in another world to acknowledge the importance of this psychological or “spiritual” dimension of life. It is a perfectly natural phenomenon.

No Need for That Hypothesis

This brings us back to where we started, the key principle of liberalism for which we are supposed to require a religious foundation: the dignity and value of the individual human soul.

But to grasp the power and grandeur of the human mind does not require any leap of faith or specialized theology. We only need to look out at the world and observe. There is abundant evidence of the human capacity to think, to understand, to create, to build, and to express itself. There is also abundant evidence that this capacity is a necessity of our survival and the source of mankind’s greatest accomplishments: the scientific and technological achievements of the modern world; the debates that led to crucial political reforms; the highest expressions in art and music.

This provides us with all the basis we need to demand respect for the power of the human mind and to oppose any political system that attempts to crush individual thinking under the bland, brutal conformity of coercion.

If you look at everything that humans have accomplished, you realize that the individual human at the center of a godless world is not a small or pathetic figure. We are giants. Most skeptics of religion are moved, not just by what we don’t believe, but by reverence for the power of the human spirit. Consider the novels of Ayn Rand, whose atheist philosophy is built on paeans to the power of the iconoclastic innovators who move the world forward. This outlook is perhaps best expressed in the play (and film) Inherit the Wind, in dialogue given to a fictional stand-in for the real-life agnostic Clarence Darrow.

In a child’s power to master the multiplication table there is more sanctity than in all your shouted “Amens!,” and “Holy, Holies!,” and “Hosannahs!” An idea is a greater monument than a cathedral, and the advance of man’s knowledge is a greater miracle than all the sticks turned to snakes or the parting of waters.

Atheism can offer a strong spiritual foundation for liberalism—in my view, stronger than what is offered by any faith. After all, in an era of increasing unbelief, to tell people they must have faith in order to have liberalism is effectively to give up on liberalism.

Fortunately, such an alternative is unnecessary. Liberalism is a creed accessible to the honest observer of any background or tradition and requires nothing more than a grounding in the observable facts of this world.

© The UnPopulist, 2024

As the guy who contributed the Buddhism entry to this series, I feel I should note that Buddhists *are* atheists.

“In effect, Communists rejected the metaphysics of religion but kept the epistemology of faith. All the answers are already known and handed down from some existing authority, and it is a sin to doubt. It’s just that instead of believing all important truths were announced by Bronze Age prophets, the Communists held that they were announced at the last Party Congress.”

My favorite part of a great article! Keep it up, Rob!