Thanksgiving Is a Time to Re-Count the Blessings of Liberalism

Our political system’s very success makes us forget its spectacular accomplishments

The purpose or meaning of holiday traditions, rotely handed down from a distant past, can often be elusive. Halloween for example: We need the help of historians, to say nothing of psychologists, to understand the things we do on that day. But the same would not seem to be the case for good old Thanksgiving. As its name plainly announces, it calls upon us on a specific day to lift ourselves out of our daily struggle, call to mind our blessings—and to give joyous thanks for them. Everyone understands this: Thanksgiving is the festival of shared gratitude.

But plain as that may be, one can still wonder why it takes place on this particular date or time of year—why should late fall be the season of gratitude—and exactly what blessings does the holiday primarily have in mind? Why also is it all about a meal—complete with prescribed menu—as, say, New Year or the Fourth of July are not?

An informed reply to these questions does after all require looking back in history, indeed, back well before the Pilgrims’s 1621 “first Thanksgiving” (and the many rivals for this title around the same time in England and Canada), all the way back actually to the Neolithic revolution, around 10,000 BC, when human beings began the transition from the hunter-gatherer form of life to the agricultural.

In the former life, there is something intrinsically enjoyable about the daily tasks of gathering fruits and berries, and exciting about the hunt; and both occupations, when successful, bring immediate reward. Even children are able and eager to join.

But the agricultural revolution brings a fundamental change, not only in economic technologies but in the experience of life. Though more economically productive, it necessarily brings into the world the new and bitter phenomenon of “work” in the strict sense: activity that involves the forced and sustained postponement of gratification. Given the basic facts about how plants grow, agriculture requires toilsome labor—clearing, planting, tending, protecting, watering—that is separated by many long months from its hoped for but always uncertain reward: the harvest. But this long-delayed reward, when it does come, is not fleeting but lasts for many months, bringing a degree of security unknown to most hunter-gatherers. Given this new agricultural rhythm of life—long periods of toil, waiting and uncertainty and then sudden and lasting pay off—one can only imagine what harvest time must have meant to these early farming peoples. Perhaps more than any other humans who have lived on this earth, these were people who, at harvest time, knew and felt their blessings, knew exactly what they had to be grateful for. And that is why, throughout the long agricultural era and in every part of the globe where it flourished, one sees signs of the same event: a communal harvest festival which naturally took place in the late fall (or whenever the local harvest season was) and which centered, naturally, around a great feast. This may be declared the greatest, longest running party on earth.

This, then, was the real “first Thanksgiving,” the essential Thanksgiving, and the one later imitated—albeit with very significant alterations and additions—by the Pilgrims at Plymouth and many others around the globe who have competed for this honor. Indeed, the memory and appreciation of this—our original seasonal festival of gratitude—lingered on sufficiently even long after the agricultural era had given way to the industrial one; even in contemporary America where only 2% of the working population now farms, people continue to celebrate it in some form. But the harvest has now become merely a metaphor for other, more contemporary issues and objects of gratitude.

So to return, at length, to our original question, what is the meaning and purpose of Thanksgiving in the transformed context of our modern, liberal-democratic world?

One already sees traces of the answer in the Pilgrims. Their Thanksgiving celebration, while certainly celebrated a successful harvest, meant much more to them than that. The harvest was ultimately only the capstone of a very different accomplishment: their perilous voyage to America. The harvest proved that they could not only journey here safely but also survive in this new, harsh and frigid land. And of course this voyage and survival were themselves all undertaken for yet a further purpose: to escape the religious persecution they experienced at home, escape to a new land—a new world—of religious liberty. It is for this whole chain of events, but especially the last, that they were giving thanks in this first American Thanksgiving.

In doing so, the Pilgrims, in a powerful if incomplete way, point to the larger movement of the American Founders and, behind them, the European philosophers of the Renaissance and Enlightenment all of whom, if in varying degrees, were either burning to “escape” or radically transform the failed states of old Europe, full of instability, war, and persecution, and—in a change on the scale of the agricultural revolution—to replace this old world with a new one based on radically new “liberal” principles.

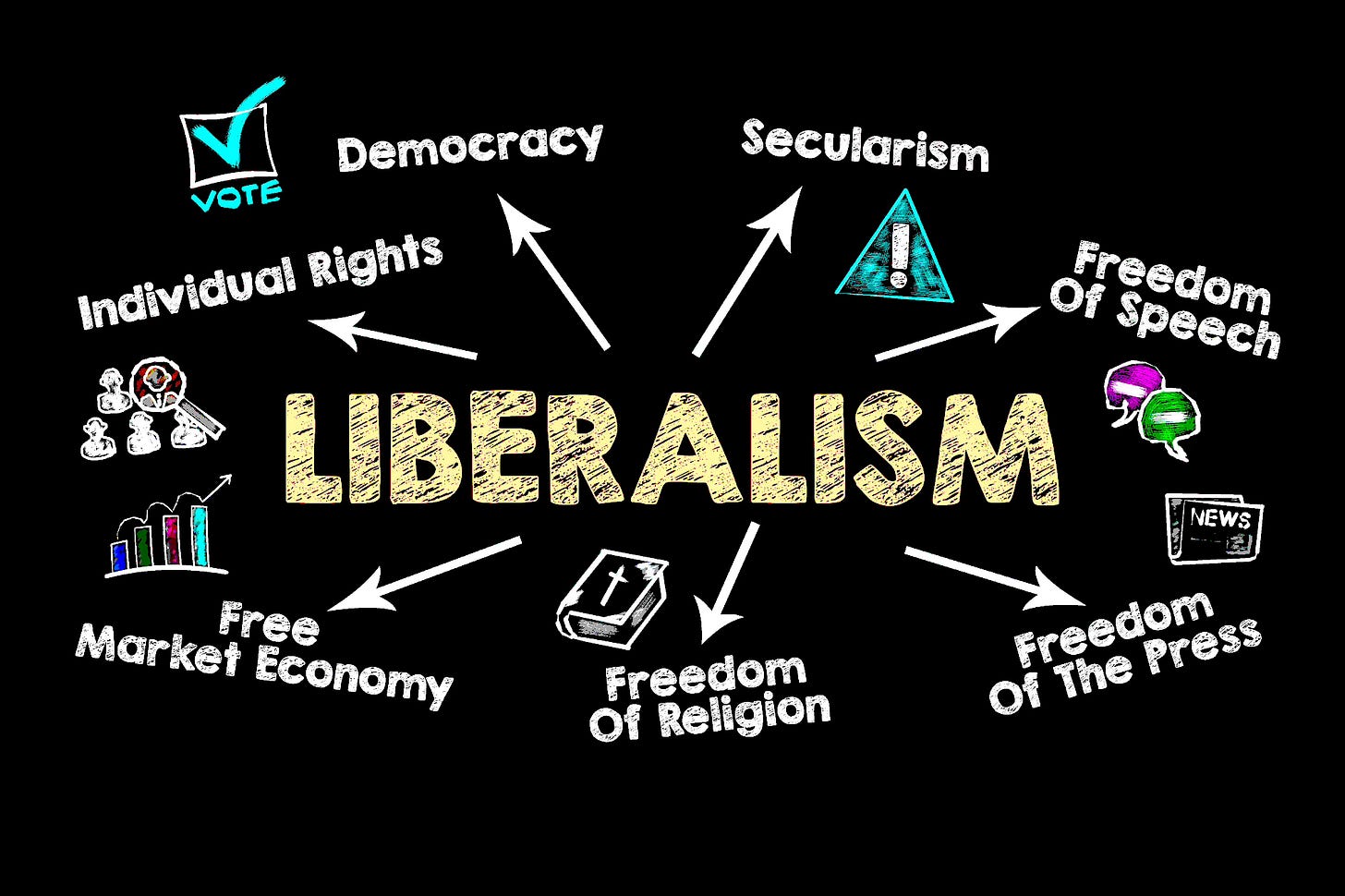

There are three familiar formulas that need to be taken together—not in isolation—to understand what the core of the liberal project is.

The first is the principle of the separation of church and state. In order to avoid religious war, political instability and persecution the state must completely abandon what had heretofore been seen as its highest purpose: the promotion and regulation of the true faith. Salvation must now be seen as a private matter between the individual and God, and not something that is the proper or legitimate concern of the state.

The second formula is that the core principle of liberalism is “limited government.” This is usually interpreted to mean the separation of powers, checks and balances, and other constitutional mechanisms for the control and limit of political power. While those mechanisms certainly form a critical element of liberal politics, still more fundamental is what we have just seen in the first formula. “Limited government” means exactly what it says: a radical retrenchment, shrinking or lowering of the whole purpose of government and political life.

The third formula for liberalism is the natural rights theory best known from the “self-evident truths” of Declaration of Independence: all humans are “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men.” This modern, liberal emphasis on human rights (as distinguished from the ancient and Christian focus on our duties) has two primary consequences. It gives this political doctrine moral urgency and power, framing it as a self-evident demand for simple justice. But what is seldom seen is that this too is still another argument for the fundamental lowering of political goals seen in the previous two formulas. For what, after all, are natural rights? They are our demands for the goods that are so basic and necessary to people—like not being killed and not being enslaved —that no one can justly be deprived of them without a justification. And the Declaration expressly states that the whole purpose of government is to secure to us these rights and that is mostly it.

What is the purpose of this liberal re-conception of government and politics to focus on such minimalist goals?

There is a simple, tragic flaw at the heart of political life. Whereas the lowest goods of life—food, shelter, safety, freedom—are self-evident to all, the higher goods—salvation, moral excellence, philosophic wisdom—are less clear and less subject to general agreement. And, from a political point of view, this simple fact makes the higher things not only elusive but positively dangerous. For, given this obscurity, the political effort to promote and enforce the loftier goods, the effort to unite nations around some settled understanding concerning these highest religious and philosophical questions, is inherently prone to sectarian conflict, persecution, and fanaticism. This was particularly the case, moreover, in the West after the Reformation, the rise of printing press, and other historical circumstances that rendered a broad and stable moral-religious consensus almost impossible.

With these fears in mind, early modern thinkers, above all John Locke, sought to replace existing forms of society with a fundamentally new kind that, as it were, stood traditional society on its head. Openly renouncing the ever-precarious attempt to define the truth about life’s highest goods, it would unite people on the promise of preventing the most obvious and basic evils. To this end, it replaces the alluring account of the best regime—the centerpiece in Plato’s Republic and other classical and Christian authors—with an opposite centerpiece: the terrifying account of the original, pre-political state of nature, understood as a condition of war, poverty, and desolation. It hopes to create a unified society based not on shared love and striving for what is best but shared gratitude for the overcoming what is worst.

The new liberal states constructed in this way have been an extraordinary success, leading to levels of political stability, prosperity, peace, and toleration never seen before. But this very success brought to light a major shortcoming, an internal contradiction. The society rests upon gratitude for evils overcome. But when evils have been overcome so successfully, we no longer actively remember them. We can’t even see that in fact they lurk just on the other side of the liberal horizon. We no longer feel the need for gratitude for our own accomplishments, unleashing a torrent of prickly discontents and frustrated longings that become the grounds for political extremism.

Thanksgiving, the festival of shared gratitude, is our small attempt to overcome this structural defect in liberal societies and stop their very success from dooming them. So let’s today re-count our blessings.

© The UnPopulist, 2024