Populism Sans the Popular Vote: A Dangerous Formula

The GOP's skewed political incentives are exacerbating America's partisan polarization

In my opening essay, “An Illiberal America Would be a Disaster for the World,” I noted:

The GOP’s rapid abandonment of its longstanding commitment to free enterprise, limited government and fiscal responsibility, and enthusiastic capitulation to Trump and Trumpism will figure among this century’s more shocking political developments.

To understand just how shocking, consider that just one year before Trump descended on the political scene, Matt Grossmann and David Hopkins, both poli sci professors, wrote in a highly influential article (which they subsequently turned into a book) that there was a basic “asymmetry” in the organizing principle of the two parties. The Republican Party and the Democratic Party weren’t involved in a duel between two competing ideologies, as per conventional wisdom. Rather, they noted, the GOP was an ideological movement whose supporters prized doctrinal purity. By contrast, the Democratic Party was a coalition of social groups whose interests the party sought to advance through concrete government action. In other words, Republicans prized ideology over interest and Democrats interest over ideology.

But with Trump, the ideology went out the window. An instinctive populist, he conjoined various right-wing factions around their various grievances. His agenda was full of internal tensions and these groups, consisting mostly of disaffected whites, had serious differences. But two things kept them united behind Trump.

One: Their shared and overwhelming hatred of the left.

Two: Trump’s genius in giving each faction its defining concern—fulfill the one issue that was paramount—causing it to bury its squeamishness about the many problems with the rest of his agenda and his personality.

Thus he managed to buy off religious conservatives’ dismay at his lack of compassion, charity and virtue by promising them pro-life jurists who’d overturn Roe vs. Wade (not to mention protect them from proliferating pronouns); working class whites’ antipathy for tax cuts for the rich by slamming foreigners and imports; libertarians’ disdain for protectionism by handing them tax cuts and deregulation; and national conservatives’ annoyance at his complete lack of foreign policy seriousness by his paeans to Western civ and restoration of American greatness. Trump made no attempt to unite all Americans behind some conception of the common good. His whole strategy was to deepen his appeal to a narrow right-wing base not broaden it to wider segments of the American population. In that sense, it shared something in common with identity politics.

All of this was contrary both to the GOP’s own pre-Trump thinking as well as standard models of political behavior.

A 2013 Republican National Committee autopsy report called the "Growth and Opportunity Project" blamed Mitt Romney’s presidential loss on the fact that he failed to run a sufficiently inclusive campaign. In the future, it noted, victory would require extensive outreach to women, African-American, Asian, Hispanic and gay voters. Oh, it also said that the GOP needed to embrace "comprehensive immigration reform.” The last, of course, sounds like a cruel joke given the GOP’s hard nativist turn under Trump.

The autopsy’s conclusions made good sense under the median voter models of political behavior, which suggest that parties abandon the political center at their peril. The vast majority of voters are almost always somewhere in the middle and hence if parties stray too far to the left or the right, other politicians will position themselves in the center and grab more votes. This dynamic was one reason why both the Republican and Democratic Parties were always jockeying to stake a middle ground pre-Trump, generating endless complaints from their more radical members about how the two parties were Tweedledee and Tweedledum—just two versions of the same thing. (Remember those days?)

One possible explanation for Trump and the current state of the GOP is that the median voter shifted between 2012 and 2016, becoming more anti-diversity, nativist, protectionist and nationalist and Trump came along and took advantage of that. But if that were the case, one would start witnessing a shift toward MAGAism in the Democratic Party. That is not happening. Democrats are going in the opposite direction, becoming more woke. And regardless of whether one regards that as a good or a bad thing, it is leading to more political polarization.

Another possible explanation would be that Trump’s election was a one-time fluke. And given that he lost his reelection bid, the GOP will start returning to the center and courting the median voter. But clearly that is not happening either. The Grand Old Party is now, even more than before the election loss, Trump’s Own Party. Members of the old guard that showed any signs of anti-Trump resistance are being systematically purged or forced out. Meanwhile, a new guard is emerging that is not only pledging fealty to Trump but embracing his MAGA agenda with renewed vigor.

The only logical conclusion is that there are bigger forces at work that have changed the median voter bell curve distribution to a barbell distribution with more voters occupying the extremes rather than the middle. One such force is the GOP’s ability to win elections without having to win a majority of voters, thanks to its Electoral College advantage. It can form a minoritarian government.

McGill University political theorist Jacob Levy points out that in the last 25 years, at no point have self-identified Republicans exceeded self-identified Democrats. “Yet this Republican minority has controlled the presidency, the House and the Senate disproportionately often over those years, winning the presidency twice on the basis of Electoral College-popular vote mismatches, and building up what has been calculated roughly a 7 percent bonus in the House such that if Democrats had won the national popular vote by 6 percent instead of 8.6 percent last November, they probably would not have recaptured control.”

Likewise, Cato Institute’s Andy Craig warns in a very astute piece that “unintended structural consequences of our electoral system” mean that we no longer have an electoral system where the “tipping point is 50/50.” “The Electoral College, the Senate, and to some degree the House and the state legislatures don’t flip from one party to the other unless we hit a tipping point that is skewed decidedly in the GOP’s favor.”

He notes that in the 19th Century, only three times did the Electoral College award the presidency to a man who was a popular runner-up and not the winner. But in the first two decades of the 21st Century, Republicans twice won the presidency while losing the popular vote (Bush, 2000 and Trump, 2016) and almost did so again in the last election. “Just a few tens of thousands of votes in a handful of states stood between Trump and a second term even though Joe Biden had thumped him by more than seven million votes nationwide, or almost four and half percent,” Craig notes.

Indeed, Democratic voters are so inefficiently distributed (with more Democrats in safe red states than Republican voters in safe blue states) that Republicans can win with as little as 46 or 47 percent. Democrats, on the other hand, have to hit as much as 53 or 54 percent to win the presidency. And this gap is only growing. Within a few more election cycles, Craig maintains, a Republican could get into the White House despite losing the popular vote by 5 to 10 percent or even more.

This kind of partisan sorting will only exacerbate political polarization and generate dire consequences for American liberal democracy.

On the Republican side, a party that can win while getting fewer votes will be driven to be more radical, says Craig, which is exactly what has been happening. Trump is not an aberration; he’s a harbinger of things to come on the right – or, as Levy insists, Trump’s victory means that Republicans have given up on even trying to reach “pluralities of majorities of voters “and “grab any narrow victory by any means necessary.”

But such minoritarian victory won’t ultimately be satisfying to partisan conservatives. It’ll make them feel even more like a persecuted minority. “Stripped of democratic legitimacy even when they win elections, the minority party needs new justifications for why its people are somehow more entitled to rule than their opponents,” Craig says.

They will feel their “alienation across the rest of society and especially interacting with elite institutions.” They will chafe at their “minority status…in culture and business.” They will rail more against the “liberal media, progressive academia, left‐wing Hollywood, woke corporations” and exhort their “political officeholders to fight back.” They’ll consider politics and policy their “only available battleground in the culture wars.” And if winning those wars requires wielding the state power they control, then so be it.

Democrats, of course, won’t take any of this lying down either. They’ll feel their own sense of injury and injustice. As the larger party that is disproportionately denied victory by a minoritarian electoral system, the Democratic Party will get drawn into the cycle of escalating anti-constitutional politics as well. “The smaller party, with its dependence on minority rule, might become illiberal faster, but the trend on both sides leads in the same direction,” Craig maintains. “Respect for constitutional processes, the rule of law, and free speech will be undermined in the larger party no less than the smaller one because of the perceived need to fight the anti-democratic opposition at all cost.”

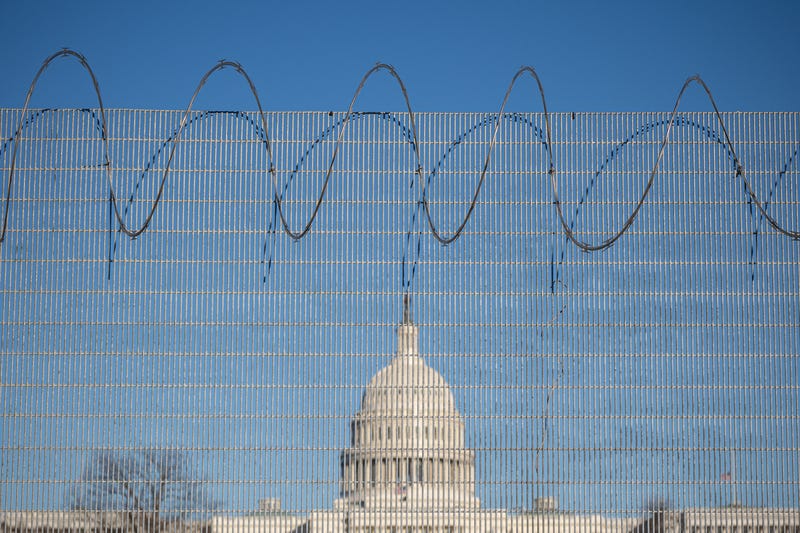

A skewed electoral system in which one party is “chronically insecure about its lack of popular mandate” and the other party is “constantly furious at the unfairness of its losses” is a dangerous thing: “The next swing of the pendulum, the next escalation of polarization, or the next partisanship-induced constitutional crisis might not end with a farcical mob being chased off after a few hours of wandering around in the US Capitol,” cautions Craig. It will lead to an ever-greater normalization of political violence, the exact opposite of how political differences are supposed to be resolved in a liberal democracy.

Avoiding this partisan doom loop will require fundamental electoral reform. Eliminating the Electoral College altogether and electing presidents with a straight popular vote, as Democrats want, is not desirable even if it were feasible. It will replace a systematic disadvantage against urban-dwelling, coastal Democrats with a systematic disadvantage against fly-over, rural Republicans, perhaps giving the latter even less of a shot at winning by authentically representing the values of their constituents than the Democrats currently have. Changing the electoral formula to strike a better balance between rural and urban interests would be better. But it’s not going to happen because even that will require amending the Constitution, which means securing two-thirds voters in Congress and getting three-quarters of the states to ratify an amendment. But of course Republicans have no reason to give up their advantage and vote for such an amendment. And if Democrats could win that many seats, there wouldn’t be a problem in the first place.

The other idea floating around is for states representing 270 electoral votes to sign a compact pledging their electors to the winner of the popular vote regardless of the election outcome in their particular state. But so far only 15 states and the District of Columbia representing 195 electoral votes have signed this compact. They are overwhelmingly blue and it is not likely that red states are going to be moved to join anytime soon. Also, its legality and constitutionality is unclear.

Craig lists some state-level reforms such as rank-choice voting that could ultimately be applied at the federal level to even things out. But whether they can be tried, tested, and applied before the partisan doom-loop brings down the country’s liberal democratic edifice is an open question.

The better option might be to defuse the culture wars by making ordinary Americans less invested in them. Politics is downstream of culture, after all. Changing the culture is never easy. But right now, it might be easier than fixing our political system. How to accomplish that is of course an elephant-sized question, best left for another day.

Must Read: Robert Kagan, a foreign policy advisor to John McCain and a Washington Post columnist, has written the single-best piece I’ve read about how Donald Trump remains a mortal danger to America. He points out that none of the checks-and-balances that our Founding Fathers constructed had anticipated the rise of a national cult figure like Trump. So, whether we realize it or not, we are already in a constitutional crisis.

Excerpt:

Most Americans — and all but a handful of politicians — have refused to take this possibility seriously enough to try to prevent it. As has so often been the case in other countries where fascist leaders arise, their would-be opponents are paralyzed in confusion and amazement at this charismatic authoritarian. They have followed the standard model of appeasement, which always begins with underestimation. The political and intellectual establishments in both parties have been underestimating Trump since he emerged on the scene in 2015. They underestimated the extent of his popularity and the strength of his hold on his followers; they underestimated his ability to take control of the Republican Party; and then they underestimated how far he was willing to go to retain power. The fact that he failed to overturn the 2020 election has reassured many that the American system remains secure, though it easily could have gone the other way — if Biden had not been safely ahead in all four states where the vote was close; if Trump had been more competent and more in control of the decision-makers in his administration, Congress and the states. As it was, Trump came close to bringing off a coup earlier this year. All that prevented it was a handful of state officials with notable courage and integrity, and the reluctance of two attorneys general and a vice president to obey orders they deemed inappropriate.

These were not the checks and balances the Framers had in mind when they designed the Constitution, of course, but Trump has exposed the inadequacy of those protections. The Founders did not foresee the Trump phenomenon, in part because they did not foresee national parties. They anticipated the threat of a demagogue, but not of a national cult of personality. They assumed that the new republic’s vast expanse and the historic divisions among the 13 fiercely independent states would pose insuperable barriers to national movements based on party or personality. “Petty” demagogues might sway their own states, where they were known and had influence, but not the whole nation with its diverse populations and divergent interests.

Such checks and balances as the Framers put in place, therefore, depended on the separation of the three branches of government, each of which, they believed, would zealously guard its own power and prerogatives. The Framers did not establish safeguards against the possibility that national-party solidarity would transcend state boundaries because they did not imagine such a thing was possible. Nor did they foresee that members of Congress, and perhaps members of the judicial branch, too, would refuse to check the power of a president from their own party.

Bonus Material: The uber thoughtful Robert Tracinski, the editor of The Symposium, a great newsletter dedicated to defending liberal values, recently had me on his podcast for a fun and wide-ranging conversation about the future of libertarianism, the corrupting alliance of libertarians and conservatives, whether the right or the is left more dangerous, and the spread of authoritarianism around the world. Go here to listen.

Copyright © The UnPopulist, 2021.

Follow The UnPopulist on X (@UnPopulistMag), Facebook (@The UnPopulist), Threads (@UnPopulistMag), Bluesky (@unpopulist.bsky.social), Instagram (@unpopulistmag), and YouTube (@TheUnPopulist)

"Eliminating the Electoral College altogether and electing presidents with a straight popular vote, as Democrats want, is not desirable even if it were feasible"

This is insulting in the extreme. It's moderate fetishism. "Sure, we COULD adopt one-man, one-vote.... but that would disadvantage perspectives that have fewer votes!"

It brings to mind the old saw that to those used to privilege, equality feels like oppression. Such a scenario would only 'disadvantage' Republicans to the precise extent that there are fewer of them.

The real danger here is that this alone is insufficient-- it would not fix the systemic biases in the House or in the Senate, and it will not address the self-selecting hyper-political nature of the Supreme Court. Actually allowing the people to elect their leaders by majority vote is presented as a hopelessly radical position, when it is the only solution that will address our ongoing legitimacy crisis.

Very nice piece, although, as Anthony Damiani points out, your objection to electing the president by a simple popular vote is specious. Also, the notion that the "old" Republican Party was ideologically "pure" is false. Although the "old" GOP talked incessantly of its determination to balance the budget, when in office they always ran up huge deficits while crafting elaborate plans for balancing the budget that, amazingly enough, were never enacted into law. Ever since 1994, the driving force of the Republican Party has been the populist nihilism of Newt Gingrich and Rush Limbaugh. Even prior to that time, an essential part of Ronald Reagan's appeal was his hatred of "welfare"--that is to say, programs that helped black people. Reagan's deep hatred of the American civil rights movement, a sentiment very much shared by William F. Buckley, William Rehnquist, and Antonine Scalia, is something that "conservatives" always manage to forget.