Our Survey Finds that Kennedy’s Supporters Are More ‘Normal’ Than He Is and Even Than Trump and Harris Supporters

Populists in his cohort, however, are more inclined than any other group to endorse aggressive use of executive power to achieve political goals

Just over four months ago, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. was an independent candidate for president with a small base of support. This support, however, was large enough to swing a close election to either Democrat Kamala Harris or Republican Donald Trump. Now he stands as Trump’s nominee for secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, after withdrawing from the presidential race and endorsing Trump.

It’s an opportune time, then, to look at the supporters, including the populist supporters, who helped fuel his electoral rise and place his name on more than 30 state ballots. Without their backing, Kennedy’s nomination to the cabinet of president-elect Trump—whose own campaign was driven by populist sentiments—would have been virtually unimaginable.

Just before Kennedy bowed out of the presidential contest, he was drawing support from about 4% of the electorate, according to the results of an early August survey by the Institute for the Study of Modern Authoritarianism, the parent organization of The UnPopulist. Kennedy’s percentage in the poll, which was fielded by the online research group YouGov, was consistent the findings of other surveys at the time. Our survey, however, included the Institute’s model of populism and found that about 29% of Kennedy’s followers qualified as populists—less than our estimate of 36% of Donald Trump’s supporters, but nearly twice our estimate of 15% of Kamala Harris’ supporters. The most distinctive populist feature of Kennedy’s supporters involved one of the four populist attitudes the survey measured: their uniquely high readiness to allow their candidate, if elected president, to overstep legal limits on presidential power to achieve political goals.

Yet despite this intemperance and despite Kennedy’s unconventional views and candidacy, his supporters frequently appear, well, unexceptional, even conventional. On many questions, the Kennedy coalition reflected the views of Americans as a whole in ways that Trump and Harris supporters did not.

In other areas, that same coalition seemed distinctly Trumpian, and in yet others, Harrisian—an unusual commingling of “opposing” views in our polarized age. Indeed, their nonpolarization may have been precisely why they were politically homeless enough to back an independent, longshot candidate. And while Kennedy’s populist followers are just a sliver of the American electorate, their relatively large size in an upstart campaign that could have swung a presidential election is a reminder of populism’s influence in our political era—an impact that could prove larger and more lasting, our survey suggests, than populists’ numbers alone might indicate.

The Harris-Trump Coalition?

At the time our survey was fielded, from Aug. 7 to Aug. 12, Kennedy supporters were an obviously unusual group—a rump segment of the electorate. Some of his earlier followers had decamped to support Kamala Harris when she entered the race; Pew Research even found that much of her initial surge above President Joe Biden’s polling numbers came from former Kennedy backers. Those who remained behind were supporting a candidate who championed unorthodox views, questioning the American health establishment’s consensus on the value of unpasteurized milk, fluoride in drinking water, and a range of vaccines.

Kennedy’s followers’ demographics appear to stand out in a couple respects, according to our survey, though comparisons are somewhat uncertain given his constituency’s relatively small size. One is on gender: We found that 64% were women, compared to 50% of Harris supporters and 49% of Trump supporters. Another was education: 83% of Kennedy supporters did not have a college degree, compared to 60% of Harris supporters and 71% of Trump supporters.

But in most cases, Kennedy supporters seemed familiar enough: sometimes like Harris supporters, sometimes like Trump supporters, and other times like an even blending of the two.

For example, Kennedy supporters sounded like Harris supporters in that:

73% disapproved of the actions of the protesters who entered the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021

none of those who identified as Republican described themselves as MAGA Republicans

three-quarters agreed that American business elites often harm people like themselves in pursuit of the elites’ own selfish interests

a majority wanted more ways for immigrants to obtain government documents as a remedy for more orderly border flows

29% said their religion was “nothing in particular.”

At the same time, Kennedy supporters sounded like Trump supporters in that:

only a minority (33%) thought Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 presidential election was legitimate

54% thought that if elected, Kamala Harris would definitely pose a threat to American democracy

a 52% majority believed the 2024 election would be the most corrupt election in U.S. history

87% said they wanted more physical barriers at the southern border to forestall undocumented immigration

a 54% majority identified as Protestant or Roman Catholic.

Or Average Americans?

On other important questions, Kennedy supporters sounded much like average Americans, or at least more so than either Harris or Trump supporters alone. This isn’t entirely surprising: 53% of Kennedy supporters identified themselves as strict political independents, while the 47% who did not were pretty evenly divided between those who leaned or identified Democratic and those who leaned or identified Republican. Such a coalition could plausibly produce a balanced, or “middle,” view.

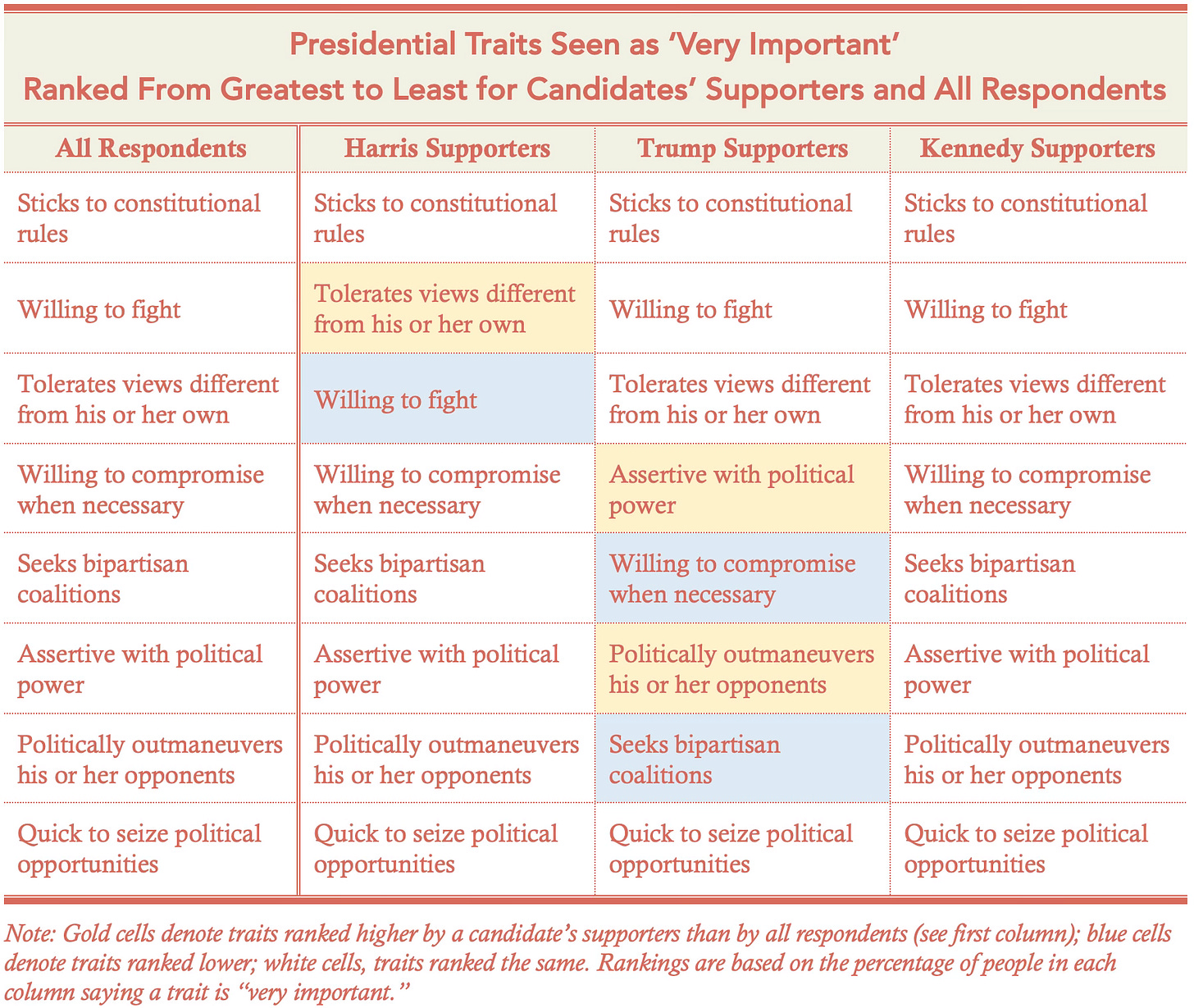

The survey asked respondents, for instance, to rate the importance of eight different traits they wanted to see in a presidential candidate. Four of the eight traits the survey listed were competitive or combative, while the other four involved norms of negotiation.

On our survey questions about traits that are important in a president, populists, at a statistically significant level, placed more importance than nonpopulists on a president’s being “willing to fight,” being “assertive with political power,” and “politically outmaneuver[ing] his or her opponents.” To be sure, populists were similarly likely to place importance on a president who “sticks to constitutional rules,” but as we noted above, they were often willing to set aside those rules for their own candidate.

The table below ranks the traits for each group of supporters by the percentage of each candidate’s followers who rated the trait as “very important.” As the table shows, Americans generally favored the presidential traits that respected the norms of negotiation, rather than Machiavellian conflict, but they still wanted their candidate to show some willingness to fight (see the first column for “All Respondents”). The order produced by Kennedy supporters perfectly matches the order favored by all the survey’s respondents, while the preferences of Harris and Trump supporters do not (differences from the rankings for all respondents are shaded in gold when higher, blue when lower, and white when the same).

In another series of questions, we asked people for their views on five controversial policy issues: abortion, transgender athletes, assault rifles, tax policy, and health care. Respondents were asked whether their views were closer to an uncompromising “progressive” answer, such as “allow all abortions no matter their reason,” or to an uncompromising “conservative” answer, such as “outlaw all abortions no matter their reason.” Respondents gave answers on a scale from 1 to 7, where 4 was “middle of the road; see the pros and cons of both sides” (see example below).

On four of the five issues, Americans’ average response was between a 3 and 4—i.e., slightly progressive—but on transgender athletes, their average was between a 5 and 6, closer to a more conservative desire to “require transgender athletes to compete on teams matching their sex assigned at birth.” As with the presidential traits, Kennedy supporters’ average answers to each question almost uniformly came closer to Americans’ average responses than did the answers of Harris supporters or Trump supporters. The sole exception came on trans athletes, where Kennedy supporters were just barely more conservative than Trump supporters (who were closer to the American average), and where Harris supporters were, by a small margin, closest to the average.

These examples of ways in which Kennedy supporters’ views alternately reflect those of average Americans, Harris supporters, or Trump supporters is not to somehow validate their views as “correct” or to dismiss as irrelevant Kennedy’s own unorthodox claims regarding, for instance, public health. Rather, it’s simply to indicate that this political minority is more conventional than is often recognized, and that its relatively high rates of populist sentiment can’t be explained simply by unlikely demographics or an abundance of “exotic views.”

This brings us to the attitudes that put many Kennedy supporters into the populist camp.

Key Populist Attitudes Among Kennedy Supporters

We measured populist sentiment by testing four potential populist attitudes and classifying as “populist” those who exhibited three or more of those attitudes. One attitude was whether someone felt an unusually direct connection with their candidate or their candidate’s agenda and believed he or she uniquely understood and would fight for them. Notably, only 6% of Kennedy supporters gave responses exhibiting this sentiment, a level comparable to the 6% of Harris supporters who did so, and considerably less than the 22% of Trump supporters who did so.

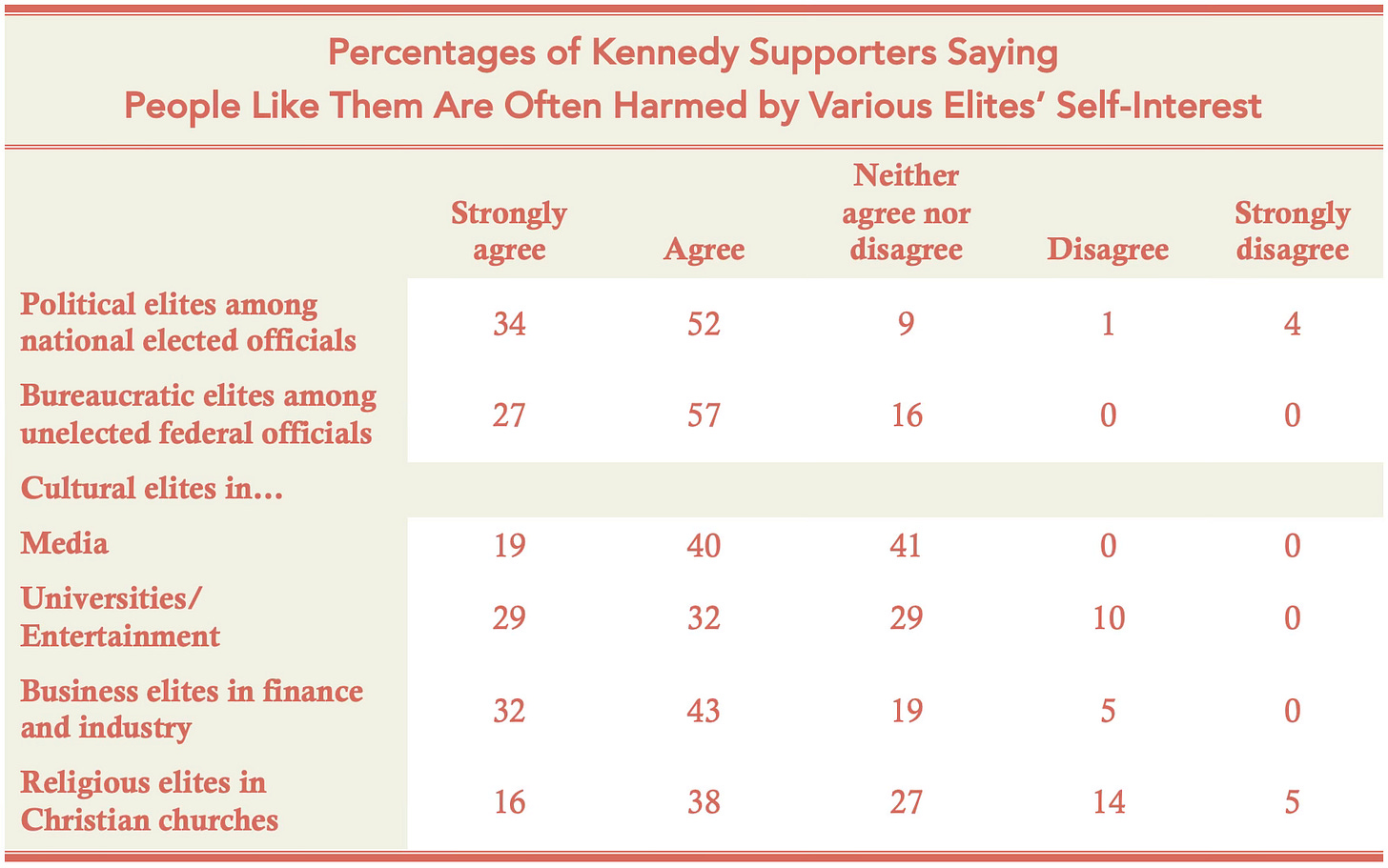

We also looked for signs the respondent saw people like themselves as being harmed or ignored by powerful societal elites who corruptly acted only in the elite’s interests. While Kennedy supporters certainly exhibited signs of this view (see table below), particularly toward national political and bureaucratic elites in the federal government, they again did so at rates lower than Harris supporters and Trump supporters: 45%, versus 59% and 61% respectively.

A third attitude we tested was whether respondents saw people like themselves as losing ground to disliked segments of society who were favored or unchecked by the elites, and whom the respondent didn’t view as able to be “real” or “true” members of the nation. Thirty-nine percent (39%) of Kennedy supporters identified at least one such “social outgroup”—most frequently “illegal immigrants”—among the 12 societal subgroups we tested, which also included racial groups, such as whites, Blacks and Hispanics; religious groups, such evangelicals, Muslims and Jews; and sexual minorities, such as gays and lesbians and transgender people. The Kennedy supporters’ percentage was higher than that of Harris supporters (22%), but lower than that of Trump supporters (54%).

In other words, relatively few Kennedy supporters felt an unusually close connection with him or his agenda; a smaller percentage expressed a strong disgruntlement with elites compared to Trump and Harris supporters; and they fell somewhere in between Trump and Harris supporters in antipathy toward social groups. But the populist trait that Kennedy supporters were more likely to exhibit than Harris and Trump supporters was the fourth one: a willingness to allow their candidate, if elected president, to overstep legal limits on presidential power to achieve their political goals. One set of questions tested their readiness to let their candidate, as president, bypass partisan congressional resistance and accomplish his or her goals unilaterally through an executive order, while another set asked whether they trusted him “as president to decide when to follow the law and when to ignore it to achieve justice” in the face of allegations that his political opposition had misused federal power for partisan purposes.

Sixty-three percent (63%) of Trump supporters endorsed one or both these ideas, as did 64% of Harris supporters. In contrast, 74% of Kennedy supporters did so—a deep disconnect with Kennedy supporters’ earlier preference for a president “who sticks to constitutional rules.” Notably, even this cognitive dissonance is reflective of Americans more broadly. Most respondents ranked a president’s sticking to constitutional rules as “very important,” yet most who did so also endorsed, in other questions, their preferred candidate’s violating limits on his or her power as president.

Kennedy Populists: A Different Mold?

Twenty-nine percent (29%) of Kennedy supporters qualified as populist under our survey’s model, having exhibited three or more of the four populist attitudes our survey explored. Interestingly, these Kennedy “populists” appear to depart from patterns we’ve seen among Trump’s and Harris’ populist followers and among populist Americans more broadly.

Trump populists and Harris populists, for instance, had a larger proportion of whites, Protestants, and people 55 years of age or older than did Trump nonpopulists and Harris nonpopulists, respectively. These differences within the Trump and Harris camps weren’t always statistically significant, but there was a statistically significant association between populists as a whole and all three factors—being over 55, white or Protestant. People in these demographic groups were thus more likely than average to be populist, rather than nonpopulist. Inversely, people who were 18 to 44—Gen Z and Millennials—were significantly less likely than average to be populist.

In contrast, Kennedy populists, compared to Kennedy nonpopulists:

had essentially the same percentage of people 55 or older

had roughly the same percentage of whites

did have a higher proportion of Protestants (41% vs. 24%), but also had a higher proportion who identified their religious views as “nothing in particular” (41% vs. 24%)—a difference not seen among Trump or Harris supporters.

Also departing from the patterns among Trump and Harris supporters, Kennedy populists, compared to Kennedy nonpopulists:

were more frequently Hispanic

had a higher percentage of Millennials, and

were entirely “working class,” meaning they included no college graduates.

Did Kennedy supporters represent a new source of populist challenge—a Kennedy-related variant of younger, working class, more Hispanic, less religiously defined populists? Ultimately, we can’t say, because the number of Kennedy populists, who were just 1% of the adult population, was too small to draw such conclusions with confidence. Even in the case of Kennedy populists’ lacking a college degree, which was statistically associated with Kennedy populism at a 95% confidence level, seems tenuous given that it wasn’t found for populists in general, Harris populists or Trump populists. The only characteristic that Kennedy populists clearly shared with other populists was their paucity of young single women, who, we have found, are nonpopulist to a statistically significantly degree.

The populist trait that Kennedy supporters were more likely to exhibit than Harris and Trump supporters was a willingness to allow their candidate, if elected president, to overstep legal limits on presidential power to achieve their political goals.

In all, the possibility of a distinctly different type of populist coalition among Kennedy supporters who often seemed ordinary—or at least no more unusual than Harris or Trump supporters—is a fascinating outcome. While we didn’t ask Kennedy supporters how much they agreed with his most controversial health and environmental claims, their views on the many topics we tested were, as discussed earlier, well within the bounds of current American opinion. What distinguished them was their holding views that seemed Trumpian in some cases and Harrisian in others—an unusual mix in our polarized age, and one for which Kennedy’s candidacy provided a home. The other key element that united them was less a personal connection with Kennedy himself than an impatience for change, one they expressed in a widespread willingness to let Kennedy, as president, circumvent the law to address injustices or to get things done in the face of perceived Democratic and Republican intransigence.

The Immediate Significance of Populism in America

So what do our findings about Trump, Harris, and Kennedy populists imply for America’s political future? Our results suggest populist voters may have a particularly significant impact on the American political system. For instance, Harris and Trump populists were likely to identify strongly with their party and follow the election news very closely, and they were similarly likely to have voted in the previous two presidential elections. Their policy views also tended to be more “extreme”: On questions about the five controversial policies discussed earlier, Trump populists were generally more conservative in their responses than Trump nonpopulists (and significantly so in four of the five cases), while Harris populists were generally more progressive in their responses than Harris nonpopulists (and significantly so in four of the five cases).

These attributes have been thought to make people disproportionately likely to vote in primary elections. How much this is true is in dispute, but the profile above does suggest populists are likely voters, and to the extent they vote in their party primaries, they have an outsized impact on our elections by helping to pick the Democratic and Republican nominees.

And populists tend to prefer a particular kind of candidate. On our survey questions about traits that are important in a president, populists, at a statistically significant level, placed more importance than nonpopulists on a president’s being “willing to fight,” being “assertive with political power,” and “politically outmaneuver[ing] his or her opponents.” To be sure, populists were similarly likely to place importance on a president who “sticks to constitutional rules,” but as we noted above, they were often willing to set aside those rules for their own candidate. For Congress, populists were also significantly more likely to prefer a member “who sticks to their principles no matter what,” rather than a candidate “who compromises to get things done.”

To be clear, the more competitive and unyielding traits we found to be associated with populism aren’t bad in themselves. Rather, they suggest an emphasis on competition and confrontation in a constitutional system that, while accommodating and even requiring such attitudes to arrive at better public policies, also requires a degree of compromise and cooperation to produce laws and programs that are seen as legitimate and acceptable to the public as a whole. In a polarized political climate, that legitimacy is vital, but it may become harder to achieve if Congress and the presidency become more inclined to confrontation than negotiation. Unfortunately, the unconstitutional shortcuts populists often endorse will only erode that legitimacy further.

ISMA’s survey is meant to serve as a measure of the popular agitation populist leaders can tap. The findings of our survey, with its widespread evidence of popular impatience not just with elites, but with democratic norms and procedures, suggest that however short-lived the Kennedy coalition’s populist “moment” may have been, a populist America may well wear many faces, increasingly affect our governing institutions, and persist for years to come.

© The UnPopulist, 2024

Follow us on Bluesky, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and X.

Is the data of this survey publicly available somewhere?