“Our Composite Nationality” by Frederick Douglass

Those races of men that have had the least intercourse with other races of men are standing confirmation of the folly of isolation

Dear Readers:

Earlier this week on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, The UnPopulist ran a piece by former Reagan official Linda Chavez on the Great Replacement Theory, currently in vogue on the populist neo-right. This theory fears that allowing immigration from non-white countries will, to put it crudely, result in the displacement and ruination of the “great white race.” It is an odious view but one with roots as old as America itself. Ben Franklin echoed some of its themes nearly 250 years ago, as Chavez pointed out.

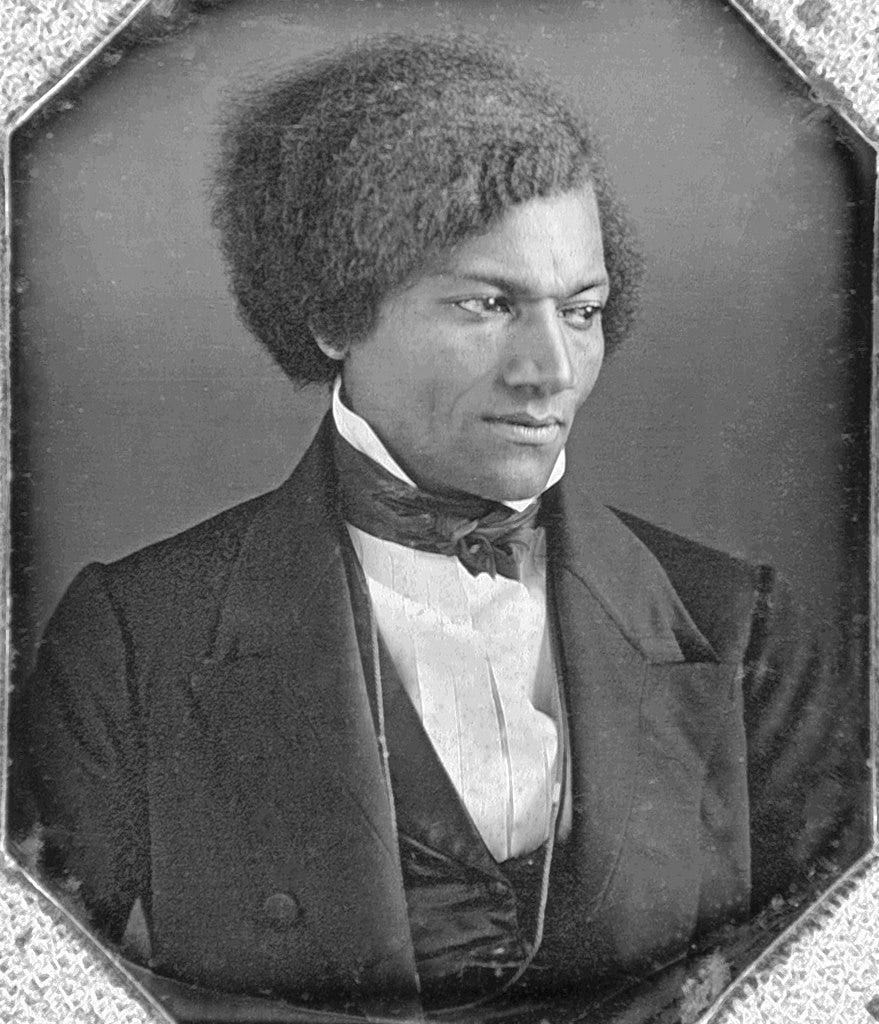

But there was one great American who never fell for it: Frederick Douglass, a freed Black who became a fierce abolitionist and a brilliant orator. In 1869, he delivered a speech in Boston titled “Our Composite Nationality” offering a beautiful ode to American cosmopolitanism. (It is also sometimes called: “Our Composite Nation.”)

He wrote this speech four years after the end of the Civil War and the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment — and one year after the U.S. signed the groundbreaking Burlingame Treaty with China. This Treaty, signed during the heyday of American industrialization when America’s need for labor was surging, recognized “the inherent and inalienable right of man to change his home and allegiance, and also the mutual advantage of the free migration and emigration of their citizens and subjects respectively from the one country to the other, for purposes of curiosity, of trade, or as permanent residents.” This is a radical statement that one finds whispered only in progressive circles nowadays. But for Douglass, who was way ahead of his time, the Treaty did not go far enough because it did not commit America to extending the full rights of citizenship to the Chinese.

Douglass predicted that Burlingame would result in a bigger influx of Chinese workers to American shores and the forces of nativism that had been gathering force with the rise of the Know Nothing movement would intensify. His speech was an impassioned attempt to nip this movement and “[l]et the Chinaman come.”

In this, he failed miserably. Indeed, 13 years after his speech, America passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, turning its back on that Treaty and enacting its first major piece of restrictionist legislation.

Nevertheless, “Our Composite Nationality” remains the most cogent and stirring statement of how pluralism and diversity strengthen — not weaken — America. There is no restrictionist argument that Douglass did not anticipate, vigorously attack and rigorously refute.

The UnPopulist is proud to excerpt this speech in a continuing celebration of one of Douglass’ most famous intellectual heirs, MLK. The cultural anxieties that immigration has ignited are at the heart of the populist authoritarian movement that has arisen in America and elsewhere. They have embittered our political discourse. Those who want to fully cleanse their palate with the sweet spirit of toleration, pluralism, and openness, would do well to read this speech in its entirety here.

Shikha Dalmia

I am especially to speak to you of the character and mission of the United States, with special reference to the question whether we are the better or the worse for being composed of different races of men. I propose to consider first, what we are, second, what we are likely to be, and, thirdly, what we ought to be…

There was a time when even brave men might look fearfully at the destiny of the Republic. When our country was involved in a tangled network of contradictions; when vast and irreconcilable social forces fiercely disputed for ascendancy and control…But that day has happily passed away. The storm has been weathered, and portents are nearly all in our favor…

The real trouble with us was never our system or form of Government, or the principles underlying it; but the peculiar composition of our people, the relations existing between them and the compromising spirit, which controlled the ruling power of the country.

We have for a long time hesitated to adopt and may yet refuse to adopt, and carry out, the only principle which can solve that difficulty and give peace, strength and security to the Republic, and that is the principle of absolute equality.

We are a country of all extremes, ends and opposites; the most conspicuous example of composite nationality in the world. Our people defy all the ethnological and logical classifications. In races we range all the way from black to white, with intermediate shades which, as in the apocalyptic vision, no man can name a number.

In regard to creeds and faiths, the condition is no better, and no worse. Differences both as to race and to religion are evidently more likely to increase than to diminish.

We stand between the populous shores of two great oceans. Our land is capable of supporting one-fifth of all the globe. Here, labor is abundant and here labor is better remunerated than anywhere else. All moral, social and geographical causes, conspire to bring to us the peoples of all other over-populated countries…

Before the relations of these two races [Black and white] are satisfactorily settled, and in spite of all opposition, a new race is making its appearance within our borders and claiming attention. It is estimated that not less than one hundred thousand Chinamen, are now within the limits of the United States…I believe that Chinese immigration on a large scale will yet be our irrepressible fact…The same mighty forces which have swept our shores the overflowing populations of Europe; which have reduced the people of Ireland three millions below its normal standard; will operate in a similar manner upon the hungry population of China and other parts of Asia…

Assuming then that this immigration already has a foothold and will continue for many years to come, we have a new element in our national composition, which is likely to exercise a large influence upon the thought and the action of the whole nation.

The old question as to what shall be done with [the] negro will have to give place to the greater question, “what shall be done with the Mongolian”… Already has California assumed a bitterly unfriendly attitude toward the Chinamen. Already has she driven them from her altars of justice. Already has she stamped them as outcasts and handed them over to popular contempt and vulgar jest. Already are they the constant victims of cruel harshness and brutal violence. Already have our Celtic brothers, never slow to execute the behests of popular prejudice against the weak and defenseless, recognized in the heads of these people, fit targets for their shilalahs. Already, too, are their associations formed in avowed hostility to the Chinese.

In all this there is, of course, nothing strange. Repugnance to the presence and influence of foreigners is an ancient feeling among men. It is peculiar to no particular race or nation. It is met with not only in the conduct of one nation toward another, but in the conduct of the inhabitants of different parts of the same country, some times of the same city, and even of the same village…

For this feeling there are many apologies, for there was never yet an error, however flagrant and hurtful, for which some plausible defense could not be framed. Chattel slavery, king craft, priest craft, pious frauds, intolerance, persecution, suicide, assassination, repudiation, and a thousand other errors and crimes, have all had their defenses and apologies.

Prejudice of race and color has been equally upheld. The two best arguments in its defense are, first, the worthlessness of the class against which it was directed; and, second, that the feeling itself is entirely natural.

The way to overcome the first argument is to work for the elevation of those deemed worthless, and thus make them worthy of regard and they will soon become worthy and not worthless. As to the natural argument it may be said that nature has many sides. Many things are in a certain sense natural, which are neither wise nor best. It is natural to walk, but shall men therefore refuse to ride? It is natural to ride on horseback, shall men therefore refuse steam and rail? Civilization is itself a constant war upon some forces in nature; shall we therefore abandon civilization and go back to savage life?

Nature has two voices, the one is high, the other low; one is in sweet accord with reason and justice, and the other apparently at war with both. The more men really know of the essential nature of things, and on of the true relation of mankind, the freer they are from prejudices of every kind…

Do you ask, if I favor such immigration, I answer I would. Would you have them naturalized, and have them invested with all the rights of American citizenship? I would. Would you allow them to vote? I would. Would you allow them to hold office? I would.

But are there not reasons against all this? Is there not such a law or principle as that of self-preservation? Does not every race owe something to itself? Should it not attend to the dictates of common sense? Should not a superior race protect itself from contact with inferior ones? Are not the white people the owners of this continent? Have they not the right to say, what kind of people shall be allowed to come here and settle? Is there not such a thing as being more generous than wise? In the effort to promote civilization may we not corrupt and destroy what we have? Is it best to take on board more passengers than the ship will carry?

To all of this and more I have one among many answers, together satisfactory to me, though I cannot promise that it will be so to you.

I submit that this question of Chinese immigration should be settled upon higher principles than those of a cold and selfish expediency.

There are such things in the world as human rights. They rest upon no conventional foundation, but are external, universal, and indestructible. Among these, is the right of locomotion; the right of migration; the right, which belongs to no particular race, but belongs alike to all and to all alike. It is the right you assert by staying here, and your fathers asserted by coming here. It is this great right that I assert for the Chinese and Japanese, and for all other varieties of men equally with yourselves, now and forever. I know of no rights of race superior to the rights of humanity, and when there is a supposed conflict between human and national rights, it is safe to go to the side of humanity. I have great respect for the blue eyed and light haired races of America. They are a mighty people. In any struggle for the good things of this world they need have no fear. They have no need to doubt that they will get their full share.

But I reject the arrogant and scornful theory by which they would limit migratory rights, or any other essential human rights to themselves, and which would make them the owners of this great continent to the exclusion of all other races of men.

I want a home here not only for the negro, the mulatto and the Latin races; but I want the Asiatic to find a home here in the United States, and feel at home here, both for his sake and for ours. Right wrongs no man…And here I hold that a liberal and brotherly welcome to all who are likely to come to the United States, is the only wise policy, which this nation can adopt.

It has been thoughtfully observed that every nation, owing to its peculiar character and composition, has a definite mission in the world. What that mission is, and what policy is best adapted to assist in its fulfillment, is the business of its people and its statesmen to know, and knowing, to make a noble use of said knowledge.

I need to stop here to name or describe the missions of other and more ancient nationalities. Ours seems plain and unmistakable. Our geographical position, our relation to the outside world, our fundamental principles of Government, world embracing in their scope and character, our vast resources, requiring all manner of labor to develop them, and our already existing composite population, all conspire to one grand end, and that is to make us the perfect national illustration of the unit and dignity of the human family, that the world has ever seen.

In whatever else other nations may have been great and grand, our greatness and grandeur will be found in the faithful application of the principle of perfect civil equality to the people of all races and of all creeds, and to men of no creeds. We are not only bound to this position by our organic structure and by our revolutionary antecedents, but by the genius of our people. Gathered here, from all quarters of the globe by a common aspiration for rational liberty as against caste, divine right Governments and privileged classes, it would be unwise to be found fighting against ourselves and among ourselves; it would be madness to set up any one race above another, or one religion above another, or proscribe any on account of race color or creed.

The apprehension that we shall be swamped or swallowed up by Mongolian civilization; that the Caucasian race may not be able to hold their own against that vast incoming population, does not seem entitled to much respect. Though they come as the waves come, we shall be stronger if we receive them as friends and give them a reason for loving our country and our institutions…Contact with these yellow children of The Celestial Empire would convince us that the points of human difference, great as they, upon first sight, seem, are as nothing compared with the points of human agreement. Such contact would remove mountains of prejudice…

The voice of civilization speaks an unmistakable language against the isolation of families, nations and races, and pleads for composite nationality as essential to her triumphs.

Those races of men, which have maintained the most separate and distinct existence for the longest periods of time; which have had the least intercourse with other races of men, are a standing confirmation of the folly of isolation. The very soil of the national mind becomes, in such cases, barren, and can only be resuscitated by assistance from without.

Look at England, whose mighty power is now felt, and for centuries has been felt, all around the world. It is worthy of special remark, that precisely those parts of that proud Island, which have received the largest and most diverse populations, are today, the parts most distinguished for industry, enterprise, invention and general enlightenment. In Wales, and in the Highlands of Scotland, the boast is made of their pure blood and that they were never conquered, but no man can contemplate them without wishing they had been conquered.

They are far in the rear of every other part of the English realm in all the comforts and conveniences of life, as well as in mental and physical development. Neither law nor learning descends to us from the mountains of Wales or from the Highlands of Scotland. The ancient Briton whom Julius Caesar would not have a slave, is not to be compared with the round, burly, a[m]plitudinous Englishman in many of the qualities of desirable manhood.

The theory that each race of men has come special faculty, some peculiar gift or quality of mind or heart, needed to the perfection and happiness of the whole is a broad and beneficent theory, and besides its beneficence, has in its support, the voice of experience. Nobody doubts this theory when applied to animals and plants, and no one can show that it is not equally true when applied to races.

All great qualities are never found in any one man or in any one race. The whole of humanity, like the whole of everything else, is ever greater than a part. Men only know themselves by knowing others, and contact is essential to this knowledge. In one race we perceive the predominance of imagination; in another, like Chinese, we remark its total absence. In one people, we have the reasoning faculty, in another, for music; in another, exists courage; in another, great physical vigor; and so on through the whole list of human qualities. All are needed to temper, modify, round and complete.

Not the least among the arguments whose consideration should dispose to welcome among us the peoples of all countries, nationalities and color, is the fact that all races and varieties of men are improvable. This is the grand distinguishing attribute of humanity and separates man from all other animals. If it could be shown that any particular race of men are literally incapable of improvement, we might hesitate to welcome them here. But no such men are anywhere to be found, and if there were, it is not likely that they would ever trouble us with their presence.

The fact that the Chinese and other nations desire to come and do come, is a proof of their capacity for improvement and of their fitness to come.

We should take council of both nature and art in the consideration of this question. When the architect intends a grand structure, he makes the foundation broad and strong. We should imitate this prudence in laying the foundation of the future Republic. There is a law of harmony in departments of nature. The oak is in the acorn. The career and destiny of individual men are enfolded in the elements of which they are composed. The same is true of a nation. It will be something or it will be nothing. It will be great, or it will be small, according to its own essential qualities. As these are rich and varied, or poor and simple, slender and feeble, broad and strong, so will be the life and destiny of the nation itself.

The stream cannot rise higher than its source. The ship cannot sail faster than the wind. The flight of the arrow depends upon the strength and elasticity of the bow; and as with these, so with a nation.

If we would reach a degree of civilization higher and grander than any yet attained, we should welcome to our ample continent all nations, kindreds [sic] tongues and peoples; and as fast as they learn our language and comprehend the duties of citizenship, we should incorporate them into the American body politic. The outspread wings of the American eagle are broad enough to shelter all who are likely to come.

As a matter of selfish policy, leaving right and humanity out of the question, we cannot wisely pursue any other course. Other Governments mainly depend for security upon the sword; our depends mainly upon the friendship of its people. In all matters — in time of peace, in time of war, and at all times — it makes its appeal to all the people, and to all classes of the people. Its strength lies in their friendship and cheerful support in every time of need, and that policy is a mad one which would reduce the number of its friends by excluding those who would come, or by alienating those who are already here.

Our Republic is itself a strong argument in favor of composite nationality. It is no disparagement to Americans of English descent, to affirm that much of the wealth, leisure, culture, refinement and civilization of the country are due to the arm of the negro and the muscle of the Irishman. Without these and the wealth created by their sturdy toil, English civilization had still lingered this side of the Alleghanies [sic], and the wolf still be howling on their summits…

The grand right of migration and the great wisdom of incorporating foreign elements into our body politic, are founded not upon any genealogical or archeological theory, however learned, but upon the broad fact of a common human nature.

Man is man, the world over. This fact is affirmed and admitted in any effort to deny it. The sentiments we exhibit, whether love or hate, confidence or fear, respect or contempt, will always imply a like humanity…

Let the Chinaman come; he will help to augment the national wealth. He will help to develop our boundless resources; he will help to pay off our national debt. He will help to lighten the burden of national taxation. He will give us the benefit of his skill as a manufacturer and tiller of the soil, in which he is unsurpassed.

Even the matter of religious liberty, which has cost the world more tears, more blood and more agony, than any other interest, will be helped by his presence. I know of no church, however tolerant; of no priesthood, however enlightened, which could be safely trusted with the tremendous power which universal conformity would confer. We should welcome all men of every shade of religious opinion, as among the best means of checking the arrogance and intolerance which are the almost inevitable concomitants of general conformity. Religious liberty always flourishes best amid the clash and competition of rival religious creeds…

I close these remarks as I began. If our action shall be in accordance with the principles of justice, liberty, and perfect human equality, no eloquence can adequately portray the greatness and grandeur of the future of the Republic.

I read the whole speech. Thank you for making me aware of it. What a masterpiece of a speech.