Key Liberal Norms Are Holding Despite America’s Polarization

But the lure of broad executive power could prove dangerous in our populist age

Editorial Tapas

One big fear about a polarized polity is that its citizens will become more willing to violate liberal democratic norms to defeat their political opponents—people they begin to see as the enemy. This concern about polarization has only increased in recent years with the emergence of populist demagogues prepared to paint liberal norms as obstacles to the “will of the people.”

To help address such issues, the cross-university, Dartmouth-based Polarization Research Lab has been measuring partisan polarization and querying Americans about their commitment to five constitutional norms in weekly surveys since September of last year. The surveys are finding clear signs of polarization across most strata of American society, but encouragingly, they also indicate that Americans largely remain supportive of the norms—with a single exception: Respondents were almost evenly divided about allowing their own party’s presidents to issue executive orders to accomplish their goals and thereby circumvent a Congress in which the opposing party is uncooperative. This result, along with the survey’s other findings on the relationship between polarization and norms, suggests polarization remains a concern for American democracy.

Measuring Partisan Polarization

How we should measure polarization isn’t obvious. A common technique is to plot, for instance, the average voting pattern of Republicans and Democrats in Congress on a pair of axes—one involving the conventional left-right spectrum on questions of government and the economy, and the other involving issues that have often divided parties, such as immigration or currency policy. Polarization is then calculated by computing the average distances between Democrats and Republicans on these axes, with larger distances implying greater ideological polarization between the parties.

The general approach now employed by the Polarization Research Lab was summarized in a 2012 journal article by scholars Shanto Iyengar, Gaurav Sood and Yphtach Lelkes. The authors proposed analyzing political polarization through “affect, not ideology,” noting, among other things, that there was no clear consensus among scholars using ideological measures on whether polarization among party leaders (such as members of Congress) was related to polarization among their political followers, and even whether average citizens were in fact ideologically polarized. The authors thus suggested tracking disparities in partisan “affect”—i.e., measuring differences in people’s feelings toward their own party and toward main opposition party. Big differences would indicate greater polarization.

Drawing on surveys from the past, the authors demonstrated that such differences in partisan feelings—differences they called “affective polarization”—provided a reasonably dependable and meaningful measurement. They also showed that by this yardstick, political polarization had increased substantially in the United States since the 1970s, primarily due to Americans’ progressively negative feelings toward the opposing party.

This partisan animus, they found, was largely independent of questions of ideology and more likely due to the growth of such things as negative political messaging, which reinforced “in-group” identity and “out-group” otherness. They further found that the rise in U.S. polarization had considerably outpaced polarization growth in the United Kingdom, suggesting that U.S. polarization was due to more than global trends.

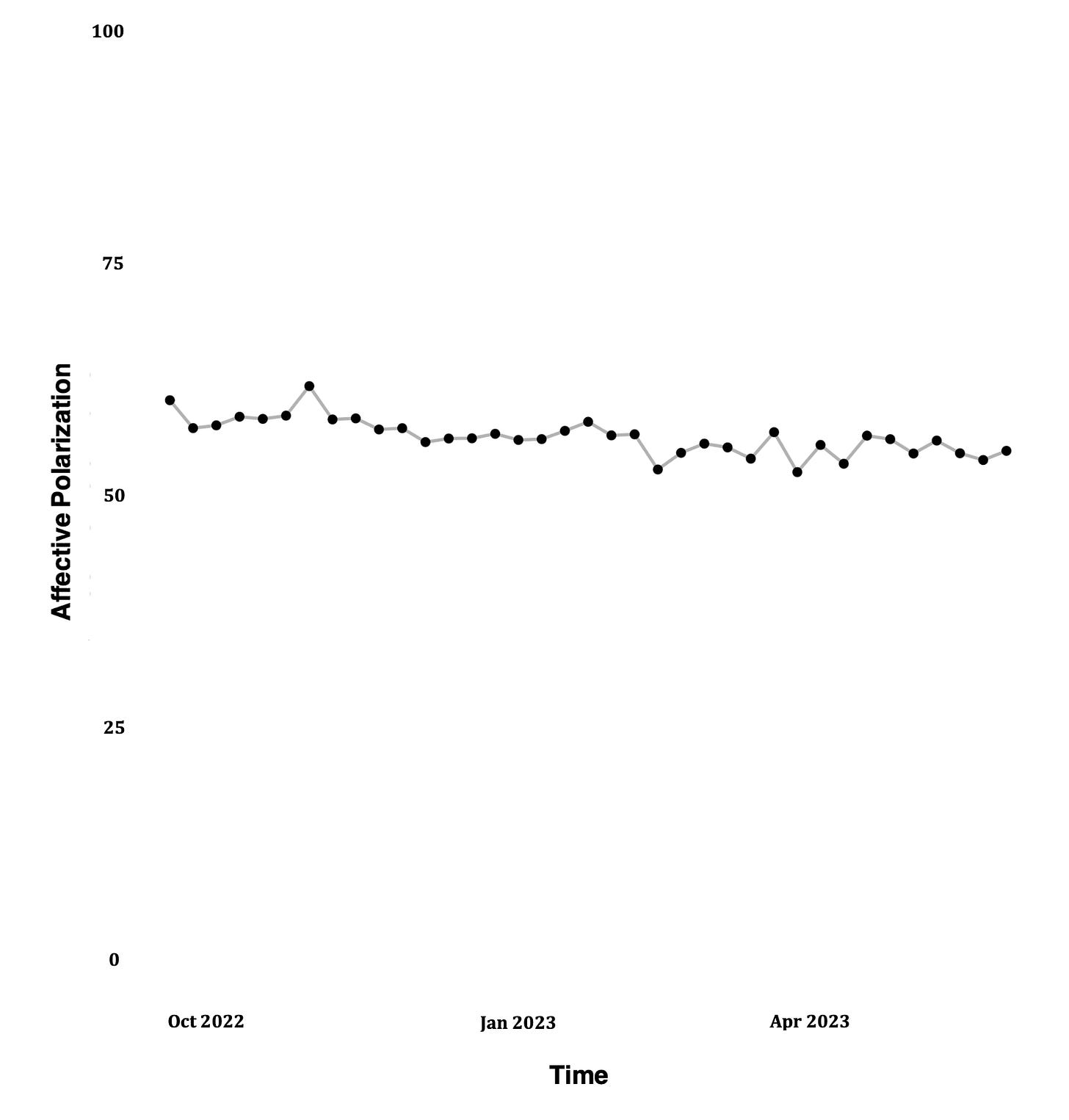

The paper has been widely cited, and last year saw the launch of the Polarization Research Lab by Iyengar, Lelkes and Sean Westwood, who directs the lab. The project, a joint endeavor of scholars at Dartmouth College, the University of Pennsylvania and Stanford University, fields a weekly survey titled America’s Political Pulse, which features a running measure of respondents’ affective polarization—the difference between Republicans’ and Democrats’ feelings about their own party members and about members of the opposing party, with both feelings measured on a scale from 0 to 100.

This approach yields a maximum affective polarization of 100 when someone rates their own party’s members’ favorability at 100 and the other party’s at 0. About 3.6% of respondents in the April 28–May 4 survey logged scores of 100, while about 3.1% registered a 0, viewing both party’s members as equally favorable. By definition, of course, the difference could also be negative, with someone rating the opposing party more highly than their own, but this is relatively uncommon, and the lab currently discounts these cases. Political independents who don’t lean toward either party also aren’t included; in the U.S., they don’t have a party of their own.

Since the APP surveys began last September, the country’s average affective polarization has ranged from a low of 52.5 in the March 24–30 survey, just before Manhattan prosecutor Alvin Bragg filed criminal charges against former President Donald Trump, to a high of 61.7 in the Oct. 28–Nov. 3 survey, just before the midterm elections (see first chart below). Excluding independents who lean toward one party or the other, Republicans and Democrats generally rank their own party somewhere in the high 70s and rank the opposing party somewhere in the low 20s, while independents who lean either Republican or Democratic generally rate the two parties more closely together. Throughout the course of the survey, Democrats have had a slightly higher average affective polarization (59.7) than Republicans (58.6), while political independents who lean either Democrat or Republican have had a lower average polarization (47.9) (see second chart below).

The poll has generally found only modest variations in affective polarization across such demographics as gender, education, race and income on average (see below).

An exception is that affective polarization tends to increase with people’s age. This trend may be related to aging itself, but it may also be related to the different experiences of generational cohorts—the Silent Generation and Baby Boomers vs. Generation X and the Millennials—or to other associated factors, such as the news consumption differences between younger and older Americans.

More decisive differences in affective polarization generally appear when people describe their political affiliations or attitudes. Thus the survey finds that people who describe themselves as “strong” Democrats or Republicans exhibit significantly higher affective polarization than “not very strong” Republicans and Democrats and than those who merely “lean” toward either party (see first chart below). Similarly, those who describe themselves as “very conservative” or “very liberal” have higher affective polarization than those who describe themselves as “moderates,” as “not sure,” or as merely “conservative” or “liberal” (see second chart below).

It’s also interesting to note the variation within the Republican Party between those who characterize themselves as “MAGA Republicans,” “Never Trumpers” or neither one. MAGA Republicans display much higher levels of affective polarization than Never Trumpers, while Republicans who describe themselves as “neither” fall almost exactly between the two.

Affective Polarization and Liberal Norms

As noted earlier, the APP surveys include five questions about supporting constitutional principles. Survey respondents are asked these questions once they’ve identified whether they favor Democrats or Republicans (if either), and the questions are then configured to inquire whether the respondent agrees or disagrees with their own party’s choosing to violate the norms and bypass the opposing party. In effect, they’re asked whether:

[Their party’s] elected officials should sometimes consider ignoring court decisions when the judges who issued those decisions were appointed by [the other party’s] presidents.

[Their party] should reduce the number of polling stations in areas that typically support [the other party].

[Their party’s] president should circumvent Congress and issue executive orders on their own to accomplish their priorities if [their party’s] president can’t get cooperation from [the other party’s] members of Congress to pass new laws.

The government should be able to censor media sources that spend more time attacking [their party] than [the other party].

[Members of their party] should be more loyal to [their] party than to election rules and the constitution when [their party’s] candidate questions the outcome of an election.

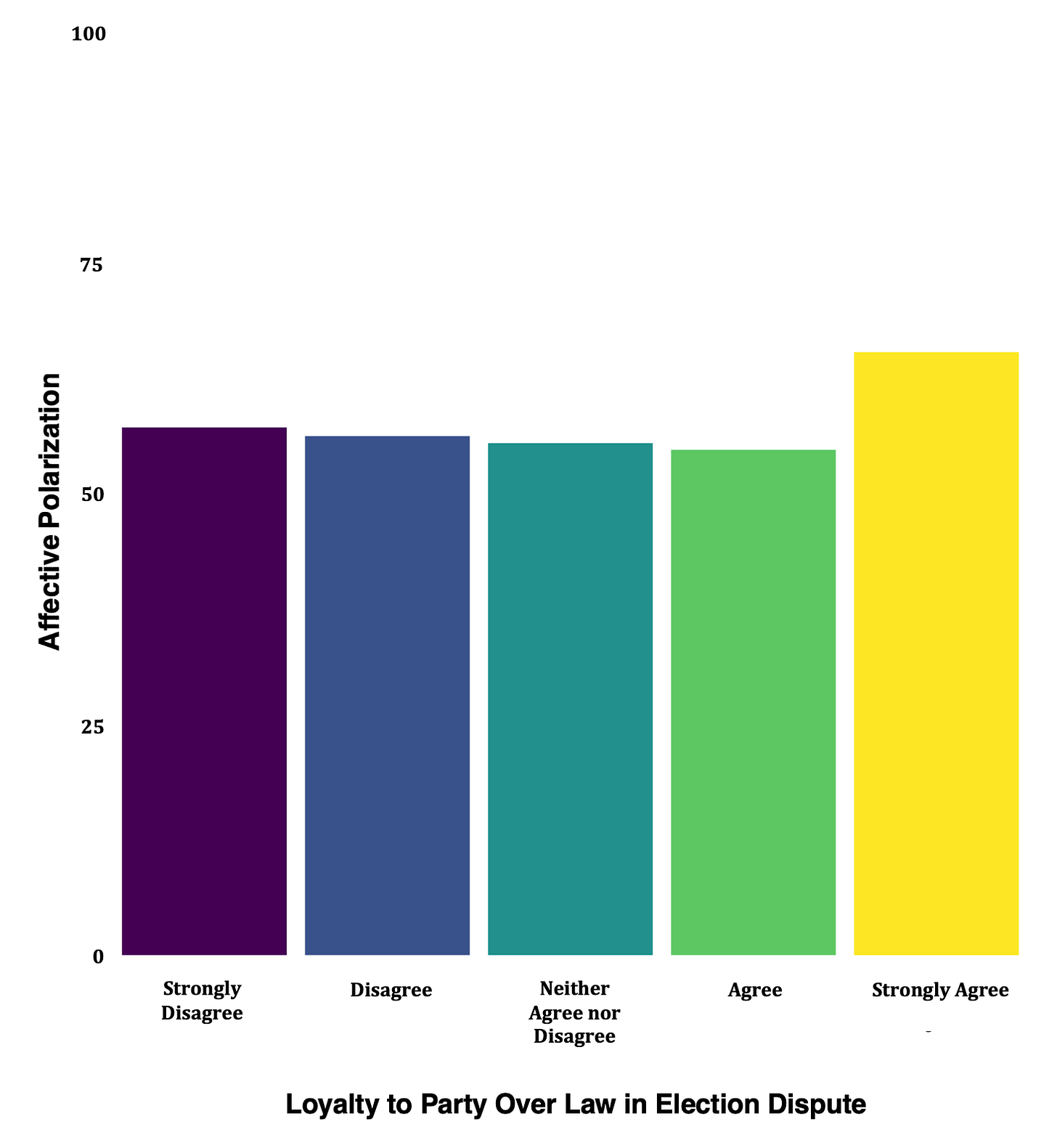

Over the course of the surveys so far, the respondents who strongly agree with each of these violations of political norms have a higher affective polarization on average than those who simply agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree or strongly disagree (see the yellow bars in the charts that follow). Perhaps the clearest example involves the use of executive orders to circumvent Congress, where acceptance of the norm violation almost rises in lockstep with affective polarization.

But in general, the relationship between polarization and a willingness to see norms defied is not so straightforward. In the case of ignoring judges appointed by the president of the other party, the level of polarization varies by less than 1.7 points from those who strongly disagree to those who agree, rising and falling before reaching the higher polarization of those who strongly agree.

Moreover, while those who strongly agree with the other three norms violations continue to exhibit the highest level of affective polarization, the second-highest level appears among those who strongly disagree with the norms violations, whether this involves censoring the other side’s media outlets, valuing party loyalty over election law in disputed races, or reducing the number of polling booths in precincts where the other party is strong. (See the purple bars below.) This finding suggests that higher levels of political polarization do not inevitably lead to a breakdown in support for liberal norms.

This point is underscored by the fact that on four of the five questions on norms, the percentage of respondents who disagree with violating the norms is significantly higher than the percentage who agree with it (see the following table, based on the April 28–May 4 survey). Regardless of polarization, in other words, most Americans support four of the five norms.

Affective polarization, then, is not decisive in destroying adherence to constitutional norms. One likely reason is that the survey’s measure of affective polarization doesn’t distinguish between people’s grounds for rating their own party higher than the other—that is, to determine whether their rationale is more “thoughtful” or “justified” than another’s. Reasons behind high affective polarization could range from inherited family biases and listening to partisan news shows to a careful reflection, say, on the state of the Republican Party since Jan. 6, 2021. There may be, in other words, rational reasons to rate one’s own party much higher than the opposing party—reasons that don’t involve a careless animosity.

And even when affective polarization contains a strong emotional component, it may be that not all of these emotional forms of political polarization are equal. A sentimental, inherited party loyalty, for instance, may prove less destructive to constitutional norms than a populist loyalty that elevates a leader’s personality above policy and allows the leader’s preferences to be a major arbiter of acceptable political action.

Against Complacency—and for Continuing Study of Political Polarization

That said, the one exception to Americans’ clear support for constitutional norms on the survey cautions against complacency and points to the potential for damage to the liberal polity if polarization isn’t contained. This exception involves using executive orders to bypass Congress.

On this question, just 33.7% of Republican and Democratic respondents in the April 28–May 4 survey disagreed with the idea, while nearly as many—32.0%—supported it. A plurality, 34.3%, neither agreed nor disagreed, suggesting they might not object if others proposed the idea.

Notably, Democrats were much more willing in that survey to embrace the use of executive orders to bypass Congress. This may be partly due to the fact that they currently hold the White House. The partisan preference might well flip, with Republicans taking the lead, if a Republican became president and Republicans didn’t control Congress.

And Republicans remain more likely than Democrats, according to that survey, to approve of placing party loyalties above election law in an election dispute—precisely the approach many Republicans hoped might give Donald Trump a second term in 2020. These two tendencies—the tendencies of Democrats on executive orders and of Republicans on election disputes—suggest that partisan polarization could become destructive when combined with the lure of presidential power.

Moreover, it is precisely the lure of strong presidential power that opens the door to populist strongmen, and pursuit of this power is the place where both the strongmen and their supporters may all too readily align at the cost of liberal values. In the end, then, no matter Americans’ current support for some key constitutional norms, we must take partisan polarization seriously.