Is Britain's Populist Movement Dying Post-Brexit?

No, it is mounting a struggle for the Tory soul

Although populism—a brew of nativism, nationalism, cultural traditionalism and authoritarianism—has been on the rise in Europe since 2005, its greatest success only occurred a little more than five years ago. In 2016, British voters narrowly approved Brexit, the decision to quit its nearly half-a-century membership in the European Union. Since then, the U.K. appears to have done better at taming the populist forces in its midst than the U.S., where the Republican Party can’t seem to extricate itself from the grip of former President Donald Trump. This appearance however is misleading.

Populism has been raging all over Europe, but its degree of political success varies. In Hungary and Poland, populist parties have been in power since 2010 and 2015, respectively. In Sweden, France, Germany and Italy populist parties don’t control the government, but they are a major political force. In Spain and Portugal, they remain a minor force although they are slightly more prominent than before. Only the Irish Republic has totally dodged this trend for reasons that have do with Irish history and the nature of Irish political culture, in particular the lack of parties based on ideology.

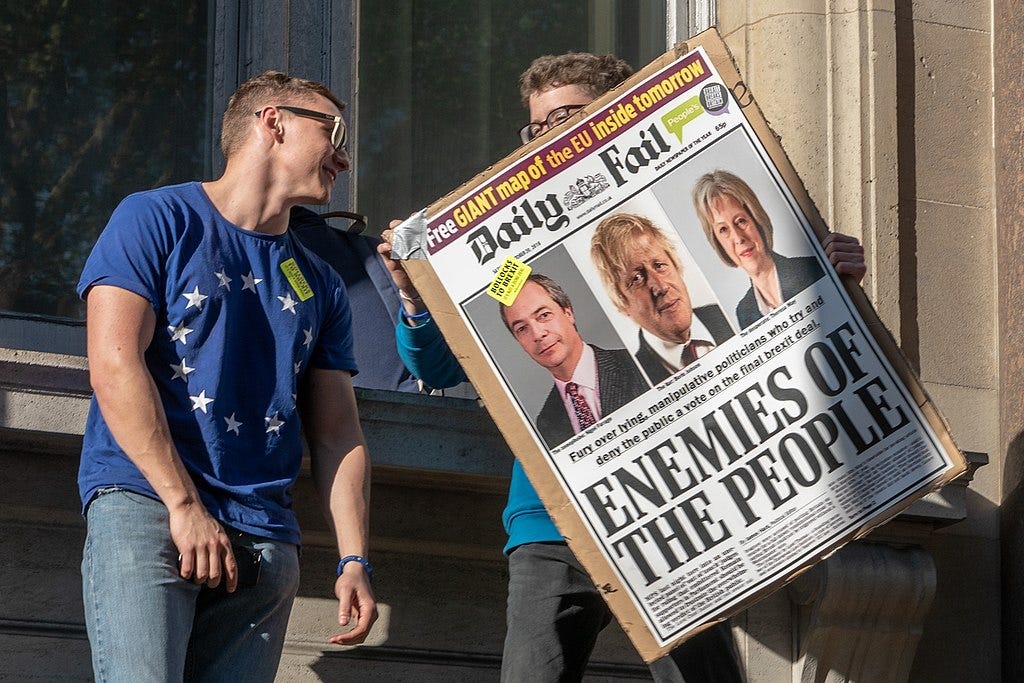

The U.K. experienced a populist wave between 2008 and 2015 with the rise of the U.K. Independence Party (UKIP) led by Nigel Farage, a bombastic rabble-rouser. The party exhibited many of the classic characteristics of populism: nativism (with a special animus against Muslim immigrants), nationalism (hence hostility to Scottish and Welsh independence), cultural traditionalism and authoritarianism. But UKIP’s signature issue was opposition to British membership in the European Union, which was of a piece with its general hostility to economic and cultural globalism. As far as UKIP is concerned, the EU is the local instantiation of a hostile global order of rules and institutions that constrains national self-government.

And by villainizing the EU, UKIP went from being a fringe party to a serious political force in a few short years. In 2014, it was (ironically) the top performer in the election for the European Parliament, winning 27.5% of the vote and becoming Britain’s largest party in that body. It subsequently won two by-elections to fill parliamentary seats prematurely vacated before the general election. Even more significantly, it got 12.6% of the 2015 general election vote. This performance was on par with populist parties elsewhere. For example, the Sweden Democrats, the nativist party in Sweden, won 12.9% in 2015, and the Austrian Freedom Party 16.2% in 2019. UKIP also built a serious presence in local government with strong performances in local elections in 2013 and 2014 – winning 143 new local council seats in the first year and 128 in the second.

And then UKIP effectively vanished. Its successor, the Reform Party, also led by Farage, tries to carry on the populist torch—focusing on opposition to COVID lockdowns and vaccination passports. But so far it has gained no real traction. So what happened, and has the populist boil been lanced for good in England?

From 2010 to 2016, when David Cameron was the Conservative or Tory prime minister, conservatives in Parliament supported gay marriage, generous immigration policies and multiculturalism. Such attitudes caused Cameron to badly underestimate the Euro-skeptic sentiment that UKIP had stirred up on his own side. That’s why he called for a referendum on Brexit in 2015, reckoning that a “no” vote would put a decisive end to the UKIP menace. But, as already noted, the “leave” vote narrowly won (52%-48%) prompting Cameron to resign.

His successor, Theresa May, however, found herself in a severe bind. Two-thirds of the Tory members of Parliament had backed “remain,” making it exceedingly difficult for her to get the various factions in her party to agree to a Brexit deal. Her failure to hammer out something satisfactory paved the way for Boris Johnson, a man with a strong populist streak who supported a hard Brexit. He overruled the pro-EU Tories and called for an early general election. This gamble paid off as conservatives won decisively in large part due to gains in traditional Labour areas in northern England that had been drifting toward UKIP.

In other words, Johnson defeated UKIP’s populism by embracing it. The idea was to absorb the populist voters by giving them some policies (particularly Brexit) and a lot of rhetoric but without fully adopting the radically anti-systemic and nationalist position of UKIP and the Brexit party. Thus, Brexit is not the only UKIP issue that Johnson has adopted. He has been touting “leveling up” or using the government to redirect investment and economic activity away from London and to the old industrial areas in the north where the working class is concentrated. He also uses harsh rhetoric against cross-Channel migration. And he is courting deliberate confrontation with the BBC, the public broadcasting behemoth that has become an object of hatred for populist voters.

However, he has held firm against some of the more radical populist demands. For instance, he has not moved to repeal the 2010 Equality Act with its protections for trans rights, something that irks the cultural traditionalists. He has also refused to withdraw from the conventions governing refugees even though that would flow naturally from his harsh anti-immigrant rhetoric.

In other words, Johnson’s Tory Party is certainly more populist than Cameron’s. However, it has also moderated and contained the more extreme elements of the populist agenda. If this trick could be pulled off over time, then the populist insurgency would be absorbed by the status quo and its threat to that status quo neutered. Initially it looked as though it might succeed due to the genius of the British political system, which allows the two major parties to contain and incorporate radical movements on their side before they become a threat to the system. For example, the Labour Party also has thwarted populists within its ranks (in this case, any possible radical socialist movement) and marginalized the Communist Party.

The U.K. can do this because, unlike some other European countries such as Sweden, Italy, Germany and the Netherlands, it does not have a pure proportional representation system and so does not have to apportion seats in Parliament based on a party’s vote share. Instead, it has what is called a “first past the post” system, in which the candidate in each parliamentary constituency who wins the most votes goes to Parliament. This means that even though UKIP obtained 12.6% of the vote in the national election of 2015, it seated only one MP because it won only one constituency. By contrast, the same share of the vote would have earned it dozens of seats in these European countries. This means that the only source of UKIP’s power is public sentiment, not actual parliamentary clout. It also means that the Tories have some breathing room from populist demands, even though UKIP supporters are among its base now.

The other reason that the Tories have avoided getting captured by populists is the undemocratic nature of U.K. party politics. Indeed, there is nothing equivalent to America’s primary system in England that would allow populists to mount a grassroots insurgency. In the U.K., both parties remain top-down organizations controlled by a relatively small political class that picks the candidates who may run for high political office. To be sure, party leaders will often support a candidate whom they may not like but who wins elections. Johnson is a good example of this— although the same Tory leaders may soon force him out thanks to the public uproar over his attendance in two parties in violation of his own COVID-19 lockdown rules. But there is no way that the voters can have a direct say in candidate selection or policy formation. That is the decision of the party’s elders and theirs alone.

This is a far cry from the United States, where Donald Trump simply went over the heads of GOP leaders and contested the Republican primaries and ultimately won his party’s nomination. And now, despite being defeated in the 2020 election, he is continuing his populist takeover of the party by fielding primary candidates who are loyal to him and his MAGA agenda rather than the party and its long-held principles. He has transformed the Republican Party in his image in a way that British populists have not managed to do with the Tory Party.

Does this mean that the world can rest easy because England has permanently defeated its populist wave? Not at all. The rise of UKIP didn’t merely have to do with Brexit, but dissatisfaction on other fronts as well. Polls indicate that a large bloc of voters is still very exercised by the country’s failure to restrict immigration even more drastically. Many also are hostile to large global firms, particularly “tech” companies. Meanwhile, the role of experts in setting policy has become more controversial during the pandemic, with a significant minority of the U.K. public actively hostile to lockdowns and other such measures. Indeed, on this count there is a fissure between the Conservative Party leadership that favors such measures and the majority of Conservative MPs, who don’t.

But it is not just issues and policies on which the Conservative Party is at odds with populist sentiment. There are broad philosophical differences too. Former Labour Party voters who supported Johnson due to Brexit aren’t crazy about the Tory commitment to free enterprise. For example, they are in favor of nationalizing the utilities rather than relying on private suppliers. Nor do they like Conservative “austerity” talk of cutting government spending in the name of fiscal discipline.

If Conservatives don’t keep tacking in a populist direction, these voters, about 20% to 25% of its current base, will become discontented—giving Farage’s Reform Party or another party an opportunity to reappear as a serious political force. But if the Tories do become more populist, they will risk an even bigger exodus of centrist voters, who comprise about a third of the party’s support.

What this means is that the Conservative Party faces a very tough choice, regardless of who its leader is. One route is to become a clearly populist party and get on board fully with the demands of the populist voters. This, though, would cost them the support of the centrist voters who stuck with them in 2019. Alternatively, the Conservatives could ditch the populist rhetoric and revert to the kind of positions they had under Cameron. But in that case, the populist volcano would erupt again in the shape of a revived and larger populist party, which could well make an electoral breakthrough. What is becoming increasingly clear, at least so far, is that trying to do both things at once only annoys and alienates both populist and centrist voters.

In other words, while the Conservative Party might have swallowed the populist baby, like Kronos devouring his children, it is proving hard to digest. So it is premature to believe that, unlike the rest of Europe, the U.K. has managed to prevent the establishment of populism as a serious political force by absorbing the populist impulse within the center-right party.

The present state of affairs is increasingly unstable. Indeed, in the next two years, one of two outcomes is highly likely. One, the Conservatives will be fundamentally transformed by their shift to the populist pole and become a populist party like the Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National in France. Or, two, they will cough up the populist voters they have swallowed, and we will see the reappearance of a separate, large and vocal populist party that is possibly even more strident than UKIP.

Neither scenario is encouraging for those who want a liberal, tolerant and open England.

Copyright © The UnPopulist, 2022.

Follow The UnPopulist on: X, Threads, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and Bluesky.

In both the US and the UK, the populists seem to be very strident in their opposition to the (imperfect) institutions that have stabilized their respective countries for half a century. What's less clear to me is what they are 'for'. There are labor shortages in both countries, yet the populists are adamantly anti-immigration. There are looming international crises that they would happily ignore in their fervent nationalism, as though ignoring the issues is equivalent to solving them. Populists in both countries decry experts and turn a blind eye to climate science, again as though ignoring a crisis means the crisis itself evaporates. What type of society will they build, what type of government, how will they address broad societal issues? There's never an answer, just heated unhinged rhetoric, goading one another to destroy, never plans for what comes next. It's like watching children play with dynamite. Am I missing something? Is there a positive to populism that makes it make sense?

"...his attendance two parties in violation..." Attendance to two parties? Attendance to parties?