How We Can Stiffen the Spine of DOJ Prosecutors Who Donald Trump Would Need to Prosecute his Political Enemies

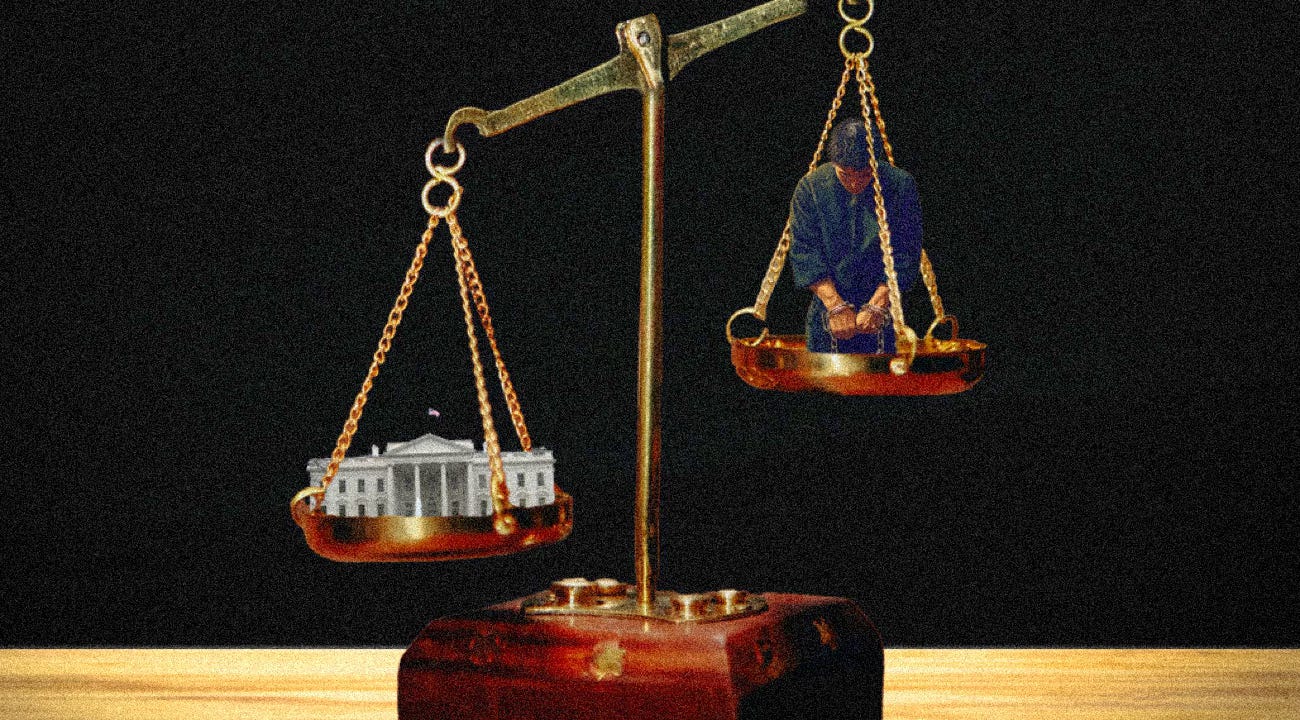

The Supreme Court’s immunity ruling weakened oversight over the abuse of executive authority but we can salvage some constitutional guardrails

Dear Readers:

A few weeks ago, we ran a piece by Pat Eddington, a senior fellow in homeland security and civil liberties at the Cato Institute, who noted that to prevent a future executive from going rogue and attempting another coup, we ought to do what most other Western countries do and place the Department of Justice under the federal judiciary, not the president.

That may be a great suggestion but it ain’t going to happen anytime soon because it would require repealing the Judiciary Act of 1789 and the 1870 law that created the DOJ and put it under the executive branch.

But, today, in the third installment in our ongoing Fireproofing the Presidency series, Conor Gaffney and Genevieve Nadeau, two brilliant legal scholars at Protect Democracy, offer more realistic solutions to stop a vindictive executive from weaponizing the DOJ to go after his political enemies. This is not a theoretical worry given that Donald Trump has all but declared his intention to do just that if he gets into the Oval Office once again.

Gaffney and Nadeau closely examine the wreckage of the Supreme Court’s recent immunity ruling that handed the executive virtually Caesar-like powers to see what guardrails could still be erected to hem him or her in. They conclude that the Bill of Rights continues to offer some legal recourse to those unfairly targeted. In addition, they suggest strengthening and enforcing norms requiring federal prosecutors to choose the Constitution over the president in the event of a conflict.

Our new editor for this series, Sarah Rumpf, a Contributing Editor at Mediaite and a political and legal commentator, worked with the authors on this essay. A delightful native of the Sunshine State, Sarah graduated cum laude from the University of Florida College of Law. After several years in private practice, she launched her own campaign consulting and election law practice, advising candidates, political parties, PACs, businesses, and nonprofit organizations. She is a prolific writer who has written on a wide variety of issues for politically diverse publications around the globe including the BBC, MSNBC, and local Fox affiliates.

For an illuminating discussion about how to make the best out of a bad hand, do read.

Shikha Dalmia

Editor-in-Chief

Of the many anti-democratic promises Trump has made for his second term, one of the most worrisome is his vow to use the awesome powers of the Department of Justice to persecute his perceived enemies. Trump is promising to investigate and criminally prosecute not only President Joe Biden and his family, but “Democrats” generally. He has promised to prosecute the Manhattan District Attorney who secured 34 felony convictions against him and also the state court judge who presided over his criminal trial. Trump has called for the arrest of poll workers after his 2020 electoral defeat, and in an interview with Univision said that “if I happen to be president and I see somebody who’s doing well and beating me very badly, I say, ‘Go down and indict them.’” For seemingly anyone who crosses him—political adversary, law enforcement official, citizen volunteering to work an election—Trump has an indictment in store.

But the norm observed by every modern presidency is that the White House should not involve itself in specific enforcement matters. To avoid actual or perceived political influence, prosecutorial decisions should be left to the independent professional judgment of prosecutors. However, in the decades since Watergate there has been a concerted effort to challenge the constitutional bases for this norm in favor of unrestrained presidential power, and now it has reached a critical moment in the candidacy of Donald Trump.

But the norm of non-interference is interwoven into the text of our Constitution, laws, and DOJ regulations and policies. These rules, enforceable to varying degrees and by different actors in and out of government, can serve as guardrails against an executive emboldened to weaponize the DOJ.

Challenging Trump’s Expansive Claims of Executive Authority

Trump’s preoccupation with using the DOJ to exact retribution is longstanding. In a 2018 interview with The New York Times, Trump claimed to have an “absolute right to do what I want to do with the Justice Department.” But does the president have an “absolute right” to direct the investigation and criminal prosecution of whomever he pleases? While the president does possess a significant amount of power over the DOJ generally, and the conservative majority of the Supreme Court recently indicated in the Trump v. United States immunity ruling that it may be willing to expand executive power beyond its historic boundaries, the answer is still no. The president’s power over the DOJ is not, as a practical or a legal matter, absolute. The Constitution prohibits prosecutions brought in retaliation for the exercise of a constitutional right or because of a defendant’s protected characteristic like race, regardless of who orders them.

In addition, federal criminal prosecutions are, like almost every executive function, conducted by an agency. That agency, the DOJ, is structured partially by Congress through statute, principal officer confirmations, and appropriations; partially by executive branch regulation and policies; and partially through practices and norms that have developed in response to political crises brought on by past presidential interference in federal prosecutions. Moreover, the DOJ is staffed by 100,000-plus professionals, many of whom, as lawyers, have sworn an oath to uphold the Constitution and hold enforceable professional ethical obligations to fairly and impartially administer the law.

Even a maximalist view of executive power over federal prosecutorial power thus runs into constraints imposed by private liberties, practical realities, and constitutional allocation of countervailing powers to Congress. The question likely to be posed by a potential second Trump presidency is how durable those constraints—enforced by the courts, individual civil servants, and by Congress—will prove in the face of an emboldened executive’s claim to an “absolute right” over the DOJ.

The President’s Powers Under Article II

Since Watergate, there has been a concerted project within the conservative legal movement to shift the contours of the law to be more accepting of aggrandized presidential power and reopen questions about presidential control over the Department of Justice. The formerly settled question of whether the president possesses the power to direct criminal investigations and prosecutions against specific individuals has actually become the subject of debate.

A number of contemporary scholars and jurists argue that when Article II of the U.S. Constitution vests “[t]he executive power” in the office of the president, this includes the power to direct and manage individual criminal prosecutions. As Justice Antonin Scalia put it, criminal prosecution “has always and everywhere—if conducted by government at all—been conducted never by the legislature, never by the courts, and always by the executive.”

But others argue, persuasively, that the president’s role in exercising that power is limited. Some scholars argue that Article II gives the president a supervisory, rather than a personal, role in the execution of the laws. Others argue that by requiring that the laws be “faithfully” executed, the Take Care Clause imposes something akin to a set of fiduciary duties on the president. Indeed, there is credible historical scholarship showing that, at the time of the founding, the phrase was understood to impose duties associated with the trust of holding public office: the duty of loyalty, a prohibition on self-dealing, and an affirmative obligation to diligently pursue the public’s interest. These fiduciary-like duties prohibit the president from interfering in specific criminal prosecutions for personal gain or to exact political retribution.

Another view emphasizes Congress’s role in structuring, through law, the executive branch. The Constitution confers on Congress broad powers “to structure the Executive Branch as it deems necessary,” including establishing executive offices and determining “their functions and jurisdiction.” When it comes to the DOJ, Congress has explicitly “reserve[d] for officers of the Justice Department” the authority to conduct “litigation in which the United States, an agency, or an officer thereof is a party.” Additionally, Congress exerts substantial control over the structure, staffing, mission, and operation of the DOJ via its constitutional powers to confirm the appointment of principal officers like the attorney general and U.S. attorneys, determine appropriations, conduct oversight, and write criminal law that the president must see “faithfully executed.”

And then there are historical norms. While American presidents have from time to time interfered in specific criminal prosecutions conducted by government lawyers, the historical tradition in this country has in the main respected conducting federal criminal prosecutions without involvement from the White House.

A Prudent Post-Nixon Reform

Nixon’s abuses of the DOJ—specifically, his interference in the federal investigation into the Watergate break-in and the purging of the special prosecutor and two attorneys general in the “Saturday Night Massacre”—provoked wide-ranging calls for measures to ensure that the White House could not interfere with the DOJ’s handling of specific investigations or prosecutions. What emerged was a formal policy, adopted by every modern administration including the Trump administration, and which has served as the keystone of the relationship between the DOJ and the White House.

This so-called “contacts policy” requires that all communications between the White House or Congress and the DOJ about particular cases be channeled through the attorney general’s office. Assistant attorneys general or U.S. attorneys and their subordinates, who are primarily responsible for the prosecution of particular cases, normally may not contact or be contacted by the White House or Congress. This communications firewall limits the ability of the White House to inquire into specific enforcement matters, thereby protecting the DOJ’s enforcement decisions “from partisan or other inappropriate influences, whether real or perceived, direct or indirect.”

The contacts policy has been understood and defended in constitutional terms from its initiation. President Jimmy Carter’s Attorney General Griffin Bell, the originator of the idea, explained that the exercise of independent professional judgment by DOJ lawyers was the surest way to assist the president in executing his duties under the Take Care Clause. Most recently, Attorney General Merrick Garland expressed the policy in constitutional terms, saying that the “only way” for DOJ lawyers to fulfill their oath to uphold the Constitution is “to adhere to the norms that have become part of the DNA of every Justice Department employee since Edward Levi’s stint as the first post-Watergate Attorney General.”

Subversion of Constitutional Norms in Trump v. United States

But in Trump v. United States, a majority of the Supreme Court expressed a starkly different view of the constitutionality of limiting the White House’s contacts with the DOJ. Chief Justice John Roberts, in an opinion at times displaying a strong vision of a unitary executive, wrote, “[T]he President may discuss potential investigations and prosecutions with his Attorney General and other Justice Department officials to carry out his constitutional duty to ‘take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.’” In the majority’s view, the president’s duties under the Take Care Clause, instead of favoring an independent DOJ whose disinterested professional judgment assists the president in overseeing the faithful execution of the laws, empower the president to exercise “exclusive authority over the investigative and prosecutorial functions of the Justice Department and its officials.”

Although the majority never actually says that the president may “direct” prosecutions, on its face it does suggest a breathtaking view of executive power. It is unclear how far the Court might take this view in a different case. The Court’s decision only addressed the question of whether the president’s power over the DOJ precludes criminal liability for official acts that involve the agency. It did not address whether this power diminishes Congress’s ability to structure the DOJ, to regulate the conduct of its prosecutors, or to control the agency through appropriations. A case presenting those questions may draw a majority with a more modest view of executive authority.

The majority’s opinion in Trump v. United States cites a dissent by Justice Antonin Scalia in a 1988 case, Morrison v. Olson, in which an eight-justice majority upheld structural prosecutorial independence as constitutional. In his lone dissent, Scalia argued the Constitution vests not “some of the executive power, but all of the executive power” in the presidency and gives the president “exclusive control” over that power. In Trump v. United States, Chief Justice Roberts elevated Scalia’s dissent to a majority opinion, writing that “[i]nvestigative and prosecutorial decisionmaking is the special province of the Executive Branch, and the Constitution vests the entirety of the executive power in the President.”

Textual and Historical Conflicts with the Trump v. US Majority’s Ruling

Justice Scalia’s interpretation has been criticized as ignoring both constitutional text and history. Contrary to Scalia’s assertion—now adopted by a majority of the Court — the text of Article II does not vest “all” of the executive power in the presidency. It vests “[t]he executive power” in the president. This isn’t just semantics. The framers drafted Article I to vest “[a]ll legislative Powers” in Congress, evidence that the absence of the word “all” in Article II was a deliberate choice.

In addition, the Constitution elsewhere shares executive power with Congress, contradicting the claim that the president possesses exclusive control over all executive functions. The Appointments Clause grants Congress a role in appointing executive officers, and the Necessary and Proper Clause grants Congress the power to “make all laws … necessary and proper for carrying into execution” the powers granted to the executive departments.

But more fundamentally, Scalia’s theory of executive power fails to live up to its own political virtues. His dissent begins by reminding us that the separation of powers is intended to ensure “a government of laws and not of men,” that it is “the absolutely central guarantee of a just Government,” and that without a “structured separation of powers” there is no meaningful guarantee of individual liberty. But it is difficult to see how this theory of executive power—one which permits the president to prosecute his perceived political enemies and dissenting citizens without personal consequence, excuse the wrongdoing of his cronies, and place himself above federal law—is consistent with the concept of a government of laws and not of men, where individual liberties are protected from the awesome powers of the state. In the words of Justice Robert Jackson in the landmark 1952 case Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, which examined when a president may execute the law in defiance of congressional intent, such a theory of executive power is “match[ed] ... only from the executive powers in those governments we disparagingly describe as totalitarian.”

The Bill of Rights as a Shield Against the President’s Power

A vision of executive power that grants the president total personal control over criminal investigations and prosecutions can also be contested as incompatible with the Bill of Rights. Several provisions in these constitutional amendments prohibit arbitrary and retaliatory criminal prosecutions that are compromised by improper political interference or retaliatory animus. In particular, there are three constitutional liberties at risk when the White House interferes in a criminal matter: the Due Process Clause’s guarantee of fundamental fairness, the Equal Protection Clause’s prohibition against differential treatment based on protected characteristics or the exercise of constitutional rights, and the First Amendment’s protections for expressive and associational freedoms.

First, the Due Process Clause “requires a disinterested prosecutor,” the Supreme Court held in Young v. U.S. ex rel. Vuitton et Fils S.A. “It is a fundamental premise of our society that the state wield its formidable criminal enforcement powers in a rigorously disinterested fashion, for liberty itself may be at stake in such matters.”

Because of this, prosecutions motivated by a “personal interest, financial or otherwise … raise serious constitutional questions,” the Court observed in a 1980 case, Marshall v. Jerrico, Inc. Recognizing such due process concerns, Congress explicitly disqualified at 28 U.S.C. § 528 any prosecutor or DOJ employee with a “personal, financial, or political conflict of interest, or the appearance thereof” from participation in particular investigations or prosecutions. A court may do so as well, and may go even further by vacating a conviction or dismissing a prosecution brought in violation of this precept of due process.

The Equal Protection Clause also prohibits criminal prosecutions against anyone who was unfairly singled out for law enforcement. As the Court stated in Wayte v. United States,“ [T]he decision to prosecute may not be deliberately based upon an unjustifiable standard such as race, religion, or other arbitrary classification, including the exercise of protected statutory and constitutional rights.”

Finally, the First Amendment protects the speech and associational freedoms that are targeted for restriction in a retributive criminal prosecution. As the Supreme Court made clear in Hartman v. Moore, “the law is settled that as a general matter the First Amendment prohibits government officials from subjecting an individual to retaliatory actions, including criminal prosecutions, for speaking out.” Therefore, the Court found in United States v. Vazquez, “[i]t is possible to base an action for selective prosecution … if the reason for selecting the particular person charged was to chill the exercise of that person’s First Amendment rights.”

Prosecutors’ Responsibilities and the President’s Power

There are substantial practical shortcomings, however, in relying on selective prosecution claims as a defense against a weaponized DOJ. They are most likely to succeed only after indictment, though a criminal investigation itself may be enough to destroy a private citizen’s reputation and livelihood. Retaliatory animus or other unconstitutional purpose may be difficult to prove even when it exists. And, as individual defenses, selective prosecution claims are poorly suited to litigating systemic abuses by a vindictive and unrestrained chief executive.

So what can be done now?

Rather than litigating an unconstitutional prosecution post hoc, it is far easier to curtail the abuse with rules that prohibit the initiation of illegal prosecutions in the first place. Such rules do exist, and they bind the very federal prosecutors on whom the president would have to rely on to accomplish his retributory aims. But with only weak mechanisms for enforcement, the prospect that these rules will meaningfully curtail abuses of presidential power depends largely on the fortitude and moral courage of individual prosecutors to uphold their constitutional and professional duties—either by refusing to initiate an illegal prosecution, or withdrawing and denying the president the benefit of their abilities.

Unlike private attorneys, who owe a primary duty of advocacy on behalf of their clients, a federal prosecutor is “the representative not of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all,” with an overarching duty not to “win a case, but that justice shall be done,” as the Supreme Court stated in Berger v. United States.

Accordingly, prosecutors have special ethical responsibilities, chief among them that they only bring charges they know are supported by probable cause. Prosecutors, and all lawyers, ignore these ethical obligations at their own peril. Violating the rules of professional conduct can lead to censure, suspension, and even permanent disbarment. While the profession’s self-regulation may strike some as a weak system for accountability, there have been instances in American history where the legal profession has risen to the occasion and curtailed prosecutorial overreach. Bar associations should take the proactive step of making clear that attorneys who participate in unethical and illegal prosecutions are putting their law licenses on the line, and ensure their ethics counsel are well-resourced and available to advise any prosecutor who may have doubts about the propriety of a prosecution in which they are involved.

Federal prosecutors are required by both the DOJ’s Justice Manual and the executive branch’s ethics standards to administer criminal law in a fair and even-handed manner, and are prohibited from considering a person’s “political association, activities, or beliefs” when making a charging decision. As our colleagues have elsewhere written, “Taken together, the various ethical rules and standards that govern prosecutors’ conduct collectively prohibit prosecutors from advancing politically motivated investigations or those that appear to be politically motivated.”

Refuse, Report, Resign

When faced with an order to carry out an unethical or unconstitutional prosecutorial decision, a federal prosecutor should refuse, report the violation, and if necessary resign. Obviously any of these choices would come at significant professional and personal cost, and those consequences have no doubt cowed many career prosecutors into following orders they know are improper. But others have chosen to uphold their oaths and their ethical obligations, and the strategy of refusal and threatened resignations worked. The same could certainly happen in a second Trump presidency.

These tools—indirect congressional control, enforcement of individual rights, and the conscience of public servants—may seem meager in the face of unbridled executive power. But in practice they do have the potential to be quite powerful. The president depends on career DOJ attorneys to prosecute cases, and on the courts to administer and oversee cases. Ultimately, no prosecution can proceed if a court determines it to be unconstitutional or if a prosecutor refuses to carry it out. While structural separation between the White House and the DOJ may be increasingly in doubt following the Supreme Court’s decision in Trump v. United States, these points of prosecutorial independence remain vital.

© The UnPopulist, 2024

Prosecution of political opponents began when the DNC went after Trump in an attempt to stop him. It's so blatantly obvious that even people on the Left now see it and call it out.

They tried to create a false smear against him in 2016 (funded by Clinton) saying he colluded with Russians.

They captured the majority of Legacy media and turned it against him, constantly pressuring the public with propaganda and lies / half truths.

They tried to impeach him twice unsuccessfully.

When none of those things worked, they moved around laws and fabricated reasons to go against him legally, moving against a former President in an unprecedented manner.

And finally, after all the evil, propaganda rhetoric, an assassination attempt.

And they did it being guilty them themselves of some of the greatest crimes perpetrated against American people. Forcing people to believe Biden wasn't senile when he always was?

Justice is a dish best served cold and it needs to be served out. It's time to keep the Left as accountable as they tried to keep Trump 'accountable'. The cult needs to be held accountable.

You will likely appreciate this podcast on the Authority Deception:

https://soberchristiangentlemanpodcast.substack.com/p/s1-authority-deception-rebroadcast