France’s Far-Right National Rally Has Lost the Battle, Not the War

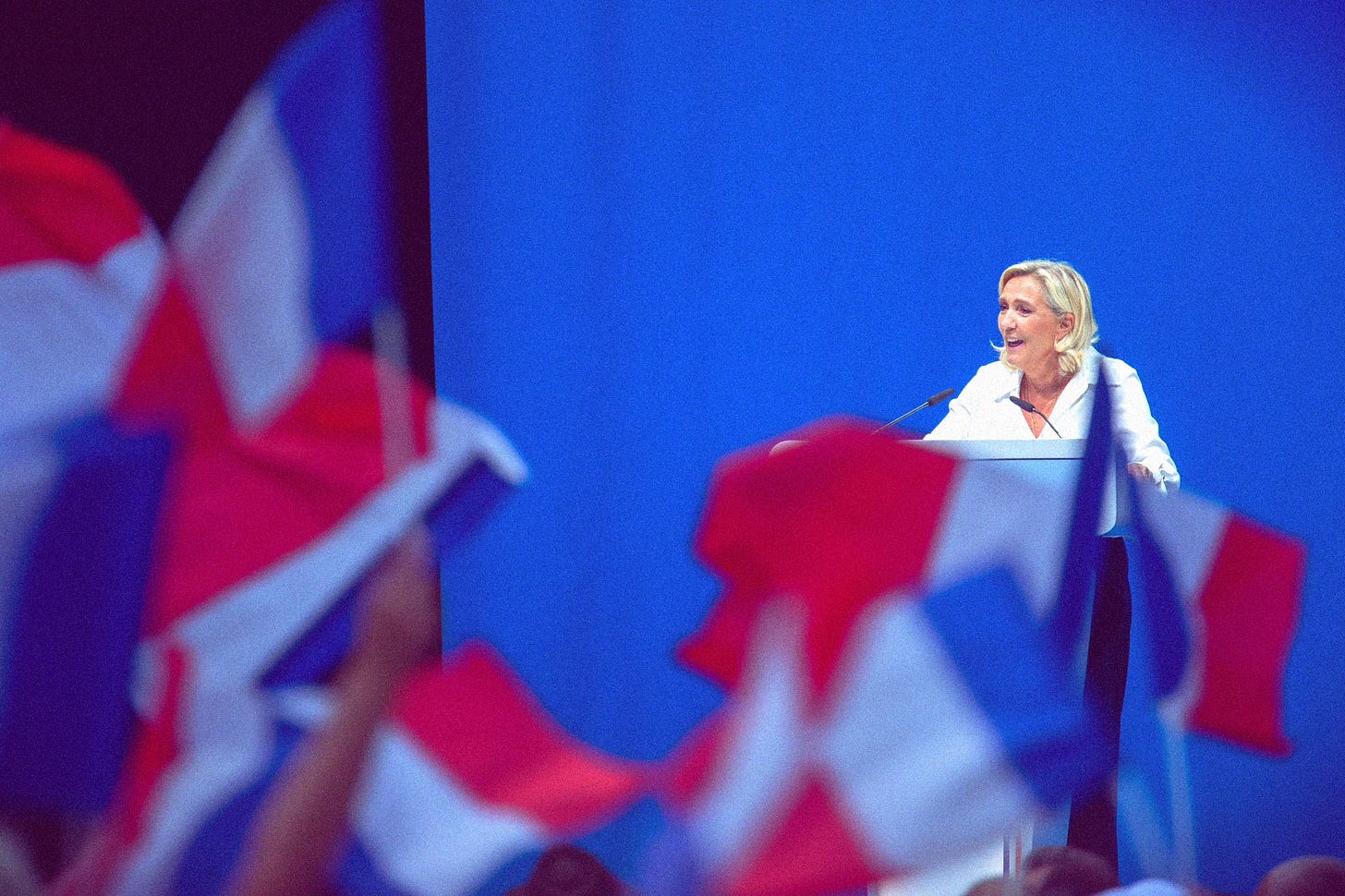

Its leader Marine Le Pen has moved French politics in a rabidly nativist direction, positioning herself for victory next time

This time, it was close.

France’s snap legislative elections in June and July were widely believed to be the far-right National Rally’s best-ever chance to clinch real power after decades spent in the opposition. In the first round of voting, Marine Le Pen’s right-wing populist-nationalist party, whose overriding policy commitment is hostility to immigration, finished in first place in over half of the races, winning the largest share of the vote nationwide. But then, in a story that has become quite familiar to the French far right, the National Rally’s hopes were dashed at the last minute. French President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist camp and France’s left-wing bloc joined forces ahead of the runoff, resulting in the National Rally falling to third place and the left ascending to first.

A History of French Resistance

The French far right has a history of being thwarted by last-ditch constitutions of broad “Republican Fronts,” ad hoc coalitions of disparate political factions or voters of different political persuasions united around keeping hard-right populists out of power. In 2002, nationalist firebrand Jean-Marie Le Pen, Marine’s father, stunned the country when he reached the second round of a presidential election for the first time, only to be obliterated by conservative incumbent Jacques Chirac, who took home over 80% of the vote. Since then, Marine has been comfortably beaten twice by Macron in presidential runoffs.

The National Rally, however, is used to playing the long game. In contrast with other nativist parties in Europe that were created after the turn of the century and experienced rapid surges in the polls in response to particular social crises, the National Rally has been a perennial—if marginal—fixture in French political life for over half a century. Founded in 1972 by Jean-Marie and several neo-fascist militants and former French members of Nazi Germany’s Waffen-SS, the National Front, as it was called until 2018, obtained a dismal 0.75% of the vote in the 1974 presidential race and couldn’t gather enough signatures to even run in the following one, seven years later. It was only in the 1980s, amid the anti-left turn in the West and the dissatisfaction of many French people with socialist President François Mitterrand, that the National Front began to improve its scores. It first gained a foothold in local and European elections and then in the 1986 legislative poll it obtained almost 10% of the vote.

At the heart of the National Front’s platform was an unwavering, very often racist, hostility towards immigrants whose numbers had soared in France between the 1950s and the early ’70s. As the country’s post-war economic expansion abruptly came to an end, the National Front didn’t hesitate to shamelessly accuse foreigners, particularly those coming from outside Europe, of sending crime rates through the roof, overburdening welfare schemes, and taking away jobs—its campaign posters famously claiming that “one million unemployed means one million immigrants too many.”

Despite incremental gains, however, the National Front and its leader, Jean-Marie Le Pen, were correctly deemed by the French people to be too toxic to govern. Le Pen publicly expressed views like: homosexuality is a “biological and social anomaly,” AIDS patients should be rounded up and locked away, the French soccer team had too many nonwhite players, and Nazi gas chambers were a mere “detail” of the history of the Second World War. In particular, the credible allegations of antisemitism against Le Pen, backed by several court convictions, effectively made him a political pariah.

A “Friendlier” Far Right?

Over the last decade-and-a-half, however, the National Rally has embarked on a major whitewashing campaign in order to increase its appeal among more moderate voters.

Marine Le Pen, who took over the reins in 2011, has been less welcoming of outright racist, antisemitic, and Holocaust-denying remarks, describing her aging father’s penchant for outrageous comments “political suicide” and ultimately expelling him in 2015. As his electoral track record showed, Jean-Marie Le Pen’s political toxicity was too significant to overcome, and his ousting was necessary to make the National Rally politically viable. In the same vein, the National Rally’s unconditional backing of Israel’s military response to the attack carried out by Hamas last October was widely seen as an attempt to underscore the current party leadership’s divergence from the founder’s attitude towards Jews and the Holocaust. Also part of these efforts is the growing prominence given by Marine Le Pen to Jordan Bardella, a fresh-faced 28-year-old with no family ties to the Le Pen clan, who was appointed party president in 2022 and has played a central role in this year’s election campaigns.

Meanwhile, the National Rally has also softened some of its most controversial policy proposals, ditching earlier plans to leave the E.U. and the eurozone and moving away from the founder’s disgust for welfare programs. Today’s National Rally presents itself as a defender of the little man against the threats posed by uncontrolled immigration and Islamist extremism, but also globalization, financial elites, and “punitive ecology.” On top of measures to limit immigration, its program includes lowering the retirement age, which Macron raised last year with a deeply unpopular reform that sparked months of protests, and rolling back energy efficiency standards for homes and vehicles, which the party maintains are disproportionately hurting the working class.

The National Rally’s shift towards a more respectable, mainstream image has made it one of the most successful (and feared) nationalist parties in Europe. Marine Le Pen’s score in presidential runoffs jumped from less than 34% in 2017 to over 40% just five years later. The National Rally’s seats in the National Assembly have gone from eight in 2017 to 89 in 2022 and 126 after the last election. The share of those who see the National Rally as a threat to democracy has fallen from 58% in early 2017 to 41% late last year, and while the party continues to do particularly well among low-income, less educated people from rural areas, its support is growing across other demographics. In the first round of the last legislative poll, it doubled its support among the most educated voters and among the residents of big cities.

Despite the party’s adjustments, however, much of its platform remains deeply worrisome to many, particularly when it comes to national identity and immigration. Just like in Jean-Marie Le Pen’s days, the National Rally continues to defend the principle of “national priority,” meaning French citizens should come before foreigners in the distribution of state aid such as unemployment benefits and social housing—even if immigrants participate in funding these schemes through their taxes and contributions. The idea has been described as “common sense” by Bardella. French law does make subtler distinctions between citizens and noncitizens, such as residency requirements to qualify for certain benefits. But the fully fledged implementation of this principle that the National Rally has in mind would fly in the face of several international treaties signed by France as well as the French Constitution, which guarantees “healthcare, material security, rest, and free time to all.” During the last campaign, the National Rally also raised eyebrows with a pledge to exclude dual nationals from certain public jobs in the fields of defense and security, in order to prevent “interference attempts orchestrated by foreign States.”

While the party’s top brass defends these proposals with a polished language that’s a far cry from Jean-Marie Le Pen’s rhetorical provocations, bad habits are hard to break; it’s undeniable that the National Rally’s transformation is more cosmetic than its leaders purport it to be. It’s not rare for the rank and file to continue to voice openly racist or Islamophobic views, including in recent weeks. During the last elections, in the race to represent the 1st constituency of Calvados in northwest France, the National Rally candidate, Ludivine Daoudi, ran in the first round but withdrew prior to the second round after a photo surfaced of Daoudi donning a Nazi hat, complete with a swastika insignia. A National Rally official accused Daoudi of exercising “bad taste” and agreed with her decision to withdraw. Meanwhile, Daniel Grenon, who represents the 1st constituency of Yonne for the National Rally, said French representatives of North African backgrounds “have no place in the high places,” meaning government. These are just two examples of many.

Supporters of Le Pen contend that her changes are commendably purging the movement of its worst elements, but to many her decisions are motivated merely by political considerations. As Tim Ganser noted in his UnPopulist profile on the far-right Alternative for Germany, one reason Le Pen’s far-right coalition in the European Parliament, Identity and Democracy, ousted the AfD from its ranks was that one of its most prominent members had suggested that being a member of the Nazi Schutzstaffel did not automatically make one a criminal. Following these remarks, Le Pen herself was vocal about not wanting to sit with the AfD anymore. But given that the German far right party had exhibited no shortage of extremism previously, Le Pen’s comments smacked of political calculation.

If it found itself in power, the National Rally would likely bring about major changes to France’s foreign policy, too. Like other far-right parties in Europe, the National Rally has long cultivated strong ties with Russia: Several of its members are involved in associations promoting the Kremlin’s views; Moscow endorses it every time the French go to the polls; and it even received a controversial multi-million-dollar loan from a Russian bank in 2014.

On the matter of the Russia-Ukraine war, while the National Rally abandoned an earlier pledge to leave NATO’s integrated command, condemned the Russian invasion, and says it supports aid to Kyiv, its actions fall far short of Macron’s pro-Ukraine stance. The National Rally opposes sending French military instructors and fighter jets to Ukraine. And when a vote was held at the National Assembly earlier this year on a Franco-Ukrainian security pact, it abstained. Following E.U. elections on June 9, in which the National Rally made historic gains in France and came out on top with over 30% of the vote, the party joined a new far-right group, Patriots for Europe, launched by the pro-Russian prime minister of Hungary Viktor Orbán with Bardella becoming its first president.

Pulling France to the Right

For now, as shown in the last election, the National Rally still alienates too many voters to gain power. But the French far right has been able to shape the country's politics in subtler ways. Faced with a hemorrhage of hardline voters to the National Rally, the mainstream conservative party, founded by President Charles de Gaulle after the Second World War and now called Les Républicains, has been increasingly tempted to veer right. This more indirect mode of influence is not exclusive to France. It bears a strong resemblance to the United States, where in less than a decade the Tea Party and then Donald Trump fundamentally reshaped the GOP along populist-authoritarian lines. And in Britain, the Conservative party has hardened its stance on issues like Brexit and immigration largely in response to the threat of populists to their right—most recently the Reform UK Party, which played an important role in the Tories’ general election debacle in July.

In France, the conservatives’ right-wing turn has been a gradual process spanning several decades. In 1991, then-party leader and future French president Jacques Chirac surprised many when he lashed out at “the noise and the smell” supposedly caused by large immigrant families. The remarks were widely seen as a deliberate attempt to imitate Jean-Marie Le Pen, who famously responded that “voters will always prefer the original to the copy.” After the turn of the century, Chirac’s interior minister and successor at the Élysée Palace, Nicolas Sarkozy, became the embodiment of the conservatives’ “Le Pen-ization,” talking of “cleaning up with a power hose” crime-ridden, largely nonwhite city suburbs, putting national identity at the center of his successful presidential campaign in 2007 by openly connecting immigration to crime and singling out the Roma people as a security problem.

The French center-right has continued to shift towards increasingly hardline positions in recent years. Last December, Macron’s centrist government joined forces with Les Républicains and the National Rally to pass a tough immigration bill that reduced foreigners’ access to a variety of welfare benefits. Several of those measures were later struck down by the country’s constitutional court, but not before Marine Le Pen had claimed an “ideological victory.” Then, last June, Les Républicains leader Eric Ciotti announced a surprise alliance with the National Rally ahead of the legislative elections, shattering decades of Gaullist tradition. The move sparked a huge uproar among virtually all the party heavyweights, who immediately expelled Ciotti. However, in between the two rounds of the recent elections, the party refused to join the centrists and the left to stop the far right—a sign that the “cordon sanitaire” built around the National Rally is cracking.

Meanwhile, the National Rally’s anti-immigration, anti-Islam narrative has been normalized in recent years by an increasingly right-wing media landscape. One of France’s most watched news channels, CNews, is often compared to the U.S.’s Fox News for its hard-right agenda. The station has been sanctioned several times by the country’s media regulator for incitement to hatred, including when one of its commentators described immigrant minors as “thieves,” “murderers,” and “rapists.” CNews is part of a sprawling media empire owned by Vincent Bolloré, an ultra-conservative tycoon dubbed the “French Murdoch” and accused of seeking to steer the country to the right by spreading toxic propaganda via his numerous outlets across print, radio, and TV.

Only A Matter Of Time?

In the recent legislative elections in France, the National Rally fell so short of expectations that the results were widely seen as a bitter defeat. But the fact is that for the first time in its history, the National Rally has now become the largest single party in the French National Assembly. With no clear majority in sight, the party’s leaders will now attempt to let their rivals consume themselves in what will likely be months of messy negotiations and unstable alliances, which they are already lambasting as deals “against nature” designed to thwart the true will of the people.

Just like Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s post-fascist Brothers of Italy, which won the country’s general election by a landslide in 2022 after watching, from the comfortable seats of the opposition, various coalitions collapse, the National Rally will once again be able to stick to its populist script without being confronted with the difficult business of governing, preparing itself for the 2027 presidential vote. “The tide is rising,” Marine Le Pen said on the evening of the legislative election runoff. “Our victory is simply postponed.”

This time around, the “Republican front” managed to stop the French far right once again. The question is whether it can continue to do so, and for how long.

© The UnPopulist 2024

“…the Tea Party and then Donald Trump fundamentally reshaped the GOP along populist-authoritarian lines. “

You obviously know nothing of the Tea Party nor its libertarian origins. Kind of makes me think you don’t know much about anything.