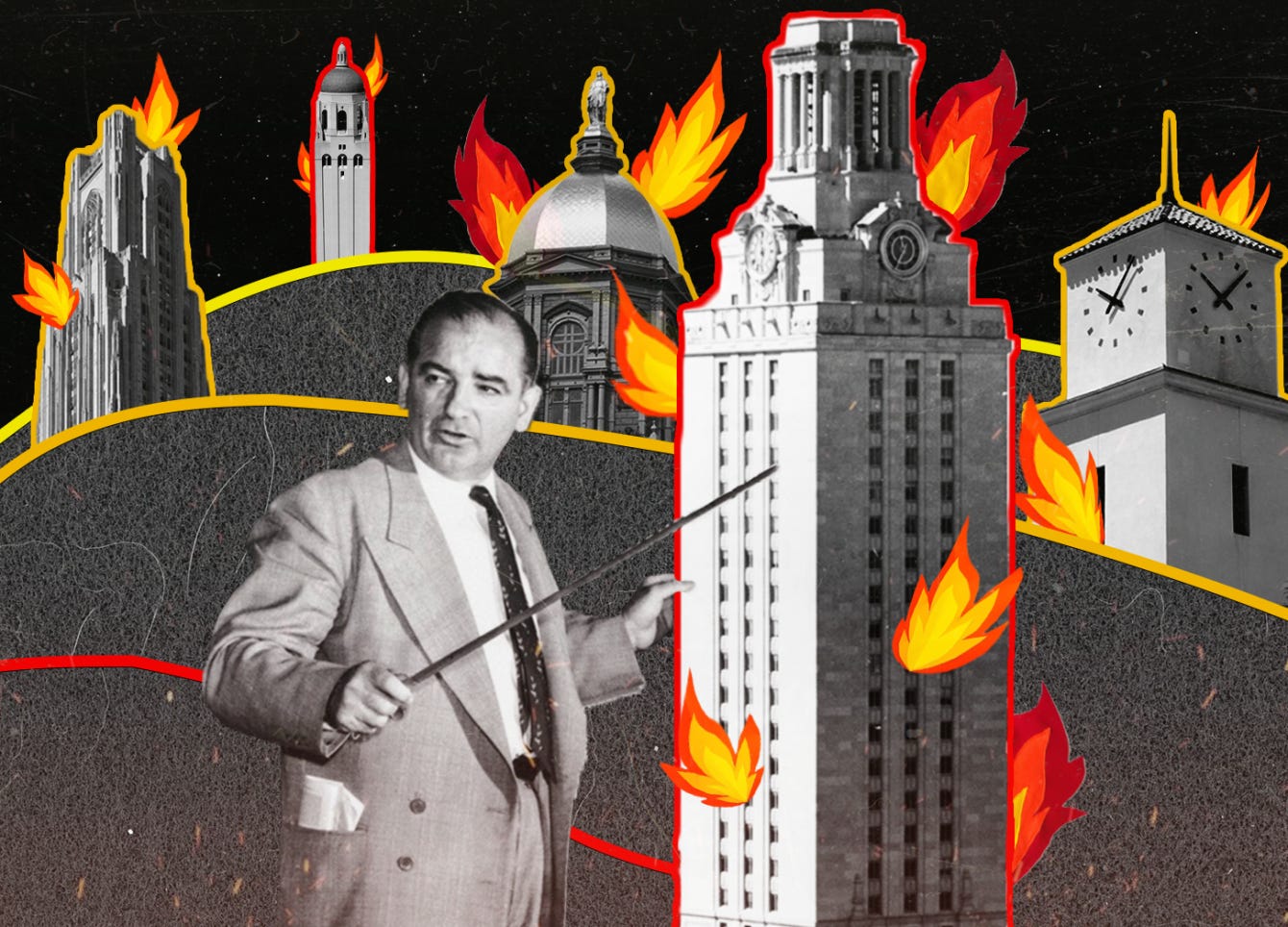

Defense of Campus Free Speech Doesn't Require Crying McCarthyism

FIRE does exceptional work in opposing repression in colleges but exaggerating the threat risks fueling right-wing radicalism

No organization defends free speech on American college campuses more effectively than the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE). It fights not only in the court of public opinion but also in real courts. When Ivette Salazar, a student at Joliet Junior College, was detained and questioned by campus security for passing out anti-capitalist flyers, FIRE helped her sue, and Joliet changed its policies. When Nicole Sanders, a student at Blinn College, faced burdensome administrative obstacles to her advocacy for gun rights, FIRE helped her sue, and Blinn changed its policies. That FIRE fights for left-wing and right-wing students and faculty alike makes it one of the few voices in campus free speech controversies that can’t credibly be accused of wielding free speech selectively as a weapon to help friends and harm enemies.

Challenging serious free speech abrogations on campuses is a worthy goal. But overstating the extent of repression on campus, as FIRE’s CEO and president Greg Lukianoff does in a recent article in the Atlantic, undermines that cause.

Lukianoff, in that article, is rightly troubled that certain college campuses sanctioned speech about the Israel-Hamas conflict in the wake of Oct. 7. Johns Hopkins University put a professor of medicine on indefinite leave while it investigates his anti-Palestinian social media posts. And Brandeis University effectively banned its Students for Justice in Palestine chapter, not over anything it did but over the national organization’s support for Hamas. Lukianoff argues, convincingly, that such episodes are part of an ongoing trend that goes beyond speech about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But then, to indicate the magnitude of that trend, Lukianoff reaches for an atom bomb of comparisons: “[E]ven McCarthyism,” he says, “didn’t seem to cause as much damage on campuses as we’ve seen in the past decade.”

False Comparison

But is that comparison warranted?

“According to the largest study at the time,” Lukianoff says, “about 100 professors were fired over a 10-year period during the second Red Scare for their political beliefs or communist ties.” Yet, in the last nine years, FIRE found “closer to 200” “professors fired for their beliefs.” If there have been nearly twice as many firings over the beliefs of scholars in recent years as there were during the McCarthy era, then that’s alarming news.

How alarmed should we be?

The study to which Lukianoff refers, The Academic Mind: Social Scientists in a Time of Crisis, was led by Paul Lazarsfeld and Wagner Thielens, both of Columbia University. It was conducted in 1955 and published in 1958 and entailed interviewing 2,451 social scientists, most of whom hailed from economics, political science, history, and sociology departments. It asked each respondent to “describe in detail any episodes in which either he, himself or his colleagues at school had been subjected to accusation and attack.” For each of 165 participating four-year colleges, Lazarsfeld and Thielens developed a “composite account of the various incidents at the school” from 1945 to 1955. Just as Lukianoff reports, of the 990 incidents Lazarsfeld and Thielens identified, about 100 resulted in a scholar or scholars being fired for their perceived political beliefs. In contrast, the Scholars Under Fire database includes around 170 firings for the nine years 2014-22. (Lukianoff starts in 2014 because that is when a major uptick in efforts to sanction scholars began. Adding 2013 for a 10-year to 10-year comparison adds just four additional terminations).

But this comparison is misleading.

First, FIRE’s Scholars Under Fire database draws from news reports and seven different trackers, including Duke Law School’s Campus Speech database and the National Association of Scholars’ Tracking Cancel Culture in Higher Education list. It is not exhaustive but it encompasses all institutions of American higher education, including community colleges and professional schools. In contrast, the 1955 Academic Mind considers the reports of some members of select departments at about 18% of the “904 accredited four-year colleges” that existed at the time. The investigators excluded professors who taught only at professional schools.

Not Apples to Apples Databases

It is a plain error to take the “about 100” political firings Lazarsfeld and Thielens find when they look at 165 of 904 colleges as the number of such firings that occurred at all colleges. If their sample of colleges were representative, we could extrapolate from their findings to conclude that around 548 professors were terminated for political beliefs or communist ties between 1945 and 1955 at four-year colleges alone. We can’t go that far because Lazarsfeld and Thielens over-sampled larger colleges, which, their data indicate, tended to experience more incidents of accusations and attacks on professors. Still, let’s take the extreme case and imagine that every one of the 739 schools not included in the study was small or very small. If we take the average number of incidents Lazarsfeld and Thielens uncovered at such schools, 3.3, and multiply by 739, we arrive at an estimate of 2,439 additional incidents. If, as with the 990 incidents in Lazarsfeld and Thielens’ sample, about 10% resulted in a politically motivated firing, that adds about 244 terminations, for a total of 344.

This is, to be sure, a very crude estimate. Although Lazarsfeld and Thielens took a random sample of small and very small colleges, it’s possible that the colleges they sampled had a higher average number of incidents than the ones they did not. On the whole, however, 244 additional terminations is likely to be a low estimate, since, in fact, the 739 schools excluded from the 1955 study include many large ones.

More Colleges But Fewer Firings Now

These studies, then, don’t support the conclusion that there have been nearly twice as many political firings in recent years as there were during the McCarthy era. A very conservative estimate places the number during the McCarthy era at 344, while the FIRE database records around 170. It would be safer to conclude that the number of firings now have been cut in half compared to the McCarthy era. That conclusion is especially striking because the number of four-year colleges and universities has nearly doubled since the 1950s. The number of faculty has expanded at an even higher rate (see table 23 at the link). The 170 firings FIRE’s database identifies are more than enough to justify free speech activism of the sort that the organization ably undertakes, but not nearly enough to justify the McCarthy comparison.

Second, although FIRE doesn’t claim otherwise, it’s worth noting that Scholars Under FIRE includes incidents of speech suppression that are not political in the sense we mean when we’re talking about McCarthyism. Five tenured professors in the database were fired in 2022 (Scholars Under Fire doesn’t tell you who is or isn’t tenured, but FIRE graciously provided me with this data). Of those five, Casey Hubble thinks he was fired for criticizing faculty workloads at McLennan Community College. Max McCoy thinks that he was fired because he publicly criticized Emporia State University’s temporary suspension of tenure, a suspension that led to the firing of over 20 tenured faculty members. Patricia Griffin of the University of Southern Maine says that she was fired for criticizing the university’s mask mandate. Mark McPhail was apparently terminated because he criticized “what he perceived as racial equity and justice issues at [Indiana University-Northwest], regularly highlighting … systemic problems on campus.” Only Michael O’Keefe, evidently fired for bringing a gay guest speaker to his class at Oklahoma Christian University, represents a clear case of a tenured professor being fired purely over his promulgation of forbidden beliefs. The rest were fired largely for criticizing their administrations. Although being fired by prickly, authoritarian administrators causes unemployment as reliably as being fired for conservative or liberal speech, only the latter fits the claim that we are in the midst of another Red Scare.

The Academic Mind interviewers, like the FIRE database, captured some firings—not used in the calculations earlier—that had nothing to do with the accusation of communist politics or associations, including conflicts with administrators. Whereas about 10% of the 990 incidents Lazarsfeld and Thielens uncovered resulted in political firing, 18% of the 990 incidents altogether resulted in firings, whether political or nonpolitical. That brings the total number of faculty firings from 1945-55 to 178 for the institutions studied, or about 617 for all four-year institutions that existed at the time if we employ the same conservative, crude method we used to estimate political firings specifically. This figure is more than three and a half times the 170 that FIRE identifies for 2014-22. To be sure, Lazarsfeld and Thielens included some charges—like a professor wearing his beard too long—that don’t fit strictly into the categories in the Scholars Under Fire database. Nonetheless, this does suggest that we are not now experiencing firings at anything like the levels of dismissal Lazarsfeld and Thielens identified.

In fairness, the Scholars Under Fire database, though it casts a wide net, cannot and does not claim to capture all cases, some of which presumably don’t make news or find their way into the seven trackers FIRE uses to supplement its own research. On the other hand, Lazarsfeld and Thielens’ interviewers, who spoke only to select social scientists, also surely missed cases.

Rising Self-Censorship, But Why?

Although professors today are not experiencing McCarthy-era levels of repression, there is evidence that they are more apprehensive and likely to self-censor than they were during the McCarthy era. When asked whether they’d toned down anything they’d written lately because they were worried it would cause controversy, only 9% of professors in the 1955 study answered in the affirmative. When FIRE conducted a survey of professors in 2022, they asked how likely respondents were to self-censor in academic publications. Fully a quarter answered “very” or “extremely likely.” This finding parallels a broader one about self-censorship in the United States. Comparing data sets going back to 1954, James Gibson and Joseph Sutherland observe that the percentage of people who report being unwilling to speak their minds has climbed dramatically since the McCarthy era, from 14% in 1954 to 46% in 2020.

Perhaps something about our political culture is more potent in producing self-censorship than political culture combined with state power was in the 1950s. Perhaps 1950s respondents were made of tougher stuff than respondents today, though their record of standing up for their colleagues was mixed at best. Perhaps heightened self-expression expectations have made us more aware of when we’re censoring ourselves. Perhaps there are more ways to get in trouble now than there were in the 1950s, when conservatives were rarely targeted. Gibson and Sutherland concede that their work “raises as many questions as it resolves.” We don’t know why reported self-censorship seems to be up nationally. And we don’t know why it seems to be up in the professoriate.

What is the harm of saying that academic firings are at McCarthy-era levels when we have reason to think they aren’t? Elizabeth Niehaus, who studied self-censorship as a 2022-23 senior fellow for the University of California National Center for Free Speech and Civic Engagement, has argued that exaggerating the challenges to free speech on campus can make students more likely to self-censor. The same can be said of faculty who, already cautious under the real threat of sanction, may become hyper-cautious when told that the threat is more potent than during the McCarthy era.

Radicalizing the Right

As Niehaus also argues, an exaggerated portrayal of the threat may help convince even some of those uncomfortable with state efforts to impose its will on universities that such efforts are the lesser of two evils. FIRE, to be sure, is having none of that. It has sued to challenge failed GOP presidential candidate and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’ Stop Woke law, which regulates the teaching of “divisive concepts” at Florida’s universities. Thanks to its efforts that law is now on hold. But others may conclude from Lukianoff’s declaration of a McCarthy-magnitude emergency that radical measures are needed to force colleges into line. If universities have permitted repression to thrive on campus, and they have proven unwilling to reform, then perhaps one should forcibly pour strong medicine down their throats. The more one thinks universities are repressive the more one winks at the repression of universities

Dazzled by the light of a supposed new Red Scare, one might fail to notice the kinds of promising developments in higher education that FIRE itself has documented. Those include a dramatic drop, since 2012, in university policies that “clearly and substantially restrict free speech,” though there has been a slight increase in the past two years. They also include the adoption by 105 colleges and universities of “free speech policy statements modeled after the “Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression” at the University of Chicago, which FIRE has endorsed.

The Scholars Under FIRE database is a valuable resource for which we should be grateful, as our data about attempts to sanction professors has otherwise been scattered. The number of terminations, not to speak of investigations, it documents in and after 2014 is still disturbingly high compared to previous recent years.

Yet if, in our eagerness to make the threat palpable, we invoke the McCarthy era, we risk facilitating the very combination of state intervention, institutional capitulation, and social pressure that characterized it. We risk making a return of the McCarthy era a self-fulfilling prophecy.

© The UnPopulist 2024

Follow The UnPopulist on X (@UnPopulistMag), Facebook (@The UnPopulist), Threads (@UnPopulistMag), Bluesky (@unpopulist.bsky.social), Instagram (@unpopulistmag), and YouTube (@TheUnPopulist)

I also am thankful that FIRE is doing the work of opposing political suppressions of free speech, and I agree that the comparison to McCarthyism isn't warranted. Being born in 1944, I have some personal experience of suppression of free speech and freedom more generally. My parents divorced, and both remarried. When I was 6-7 years old we had to move out of the city where we lived, because my sister and I were told by other kids that their parents said they couldn't play with us because our parents were divorced. Our parents got hold of our school records and changed them so it appeared that our stepmother was our birth mother. Our parents were agnostics, so they took us to the Unitarian Church so others would think they believed in God. If my Dad's religious views, which he held quietly and never made a big deal about, had been known it would have prevented him from being a Boy Scout commissioner, a role where he earned the highest volunteer award, the Silver Beaver, because of the excellent work he did. I could go on, but this is just a bit about how deeply McCarthyism reached into the society in a way that is not reflected in America today in my experience.

Just imagine if social media was around during the McCarthy era. There is a deep connection between the dominant antisocial media and the attempts to suppress free speech.

Self-censorship is a form of prudence. "Cast not your pearls before swine." But social media platforms compel us to cast what few pearls we have right into the pig trough. The whole algorithmic ecosystem is geared to recirculate resentment, recrimination and revenge. We could do with more self-censorship not less.

The whole concept of freedom of speech ("Parrhesia" Greek: παρρησία) is rooted in candid speech and speaking freely. It implies not only freedom of speech, but the obligation to speak the TRUTH for the common good, even at personal risk.

Note: Rights are not an end in themselves and every right entails obligation. In the case of free speech the obligation is to tell the truth "for the common good" not to amass clicks, likes, shares, followers and solidifying your brand.

With the willingness to speak the truth comes the danger that the truth will not be accepted exposing us to personal risk ranging from being "cancelled" to being killed. So one should probably self censor unless the need of the commonwealth or the truth is worth the personal risks.