America’s Current Prosperity Was Initially Aided by Native American Generosity

This Thanksgiving, we should express gratitude to this land’s original inhabitants and acknowledge the illiberal treatment they’ve endured

Tomorrow is Thanksgiving Day, which we celebrate during Native American Heritage Month. It’s a fitting time to reflect on the original Thanksgiving, the generosity of the Native Americans who made it possible and the imperfect legacy of our liberal polity—a polity ideally dedicated to fostering mutual tolerance, cooperation and prosperity.

Native American settlements in the New World are central to the Thanksgiving story, but the entry of the people themselves onto the continent is something only their most distant ancestors would recall. Their arrival appears to have followed some 10,000 years of dwelling on Beringia, or the Bering Land Bridge, and when they first set foot in North America, it probably seemed no different to them. Many migrated down America’s relatively ice-free West coast, perhaps in light boats, but around 15,000 years ago, some struck inland across the continent, contending with new terrain and with megafauna like the mastodon and the saber-toothed tiger.

What was truly novel for these early settlers was that—at least at first—they didn’t meet other people. As archaeologist David Meltzer put it, “One can only imagine what they thought when they got to North America south of the ice sheets and looked around and realized nobody else was home.” It may have been in equal part liberating and unnerving. Human beings had long threatened each other, but they had also learned from each other much of what they needed to survive.

This isolation disappeared over the following millennia with new waves of immigration from Siberia. By the 17th century A.D., neighboring tribes were a fact of life for the Wampanoag, or Wôpanâak, a Native American tribal confederation in the area of Cape Cod (a name an English explorer would bestow on the peninsula in 1602). The Wampanoag tribes, who spoke an Algonquian dialect, were proficient hunters and planters who engaged in seasonal migrations to fish along the Atlantic shore, but had well-defined hunting grounds to avoid conflict. Having lived in the area for an estimated 10,000 to 12,000 years, they were neatly adapted to an area that could turn deadly cold by December: They cultivated corn, beans, squash and other crops in the summer and survived the winters with stores of corn, nuts, and smoked fish and venison. They were bordered by other tribes, among them the Narragansett, whom, by 1620, the Wampanoag saw as a threat, in part because some Wampanoag tribes had been diminished by disease.

This disease, possibly yellow fever, smallpox, the plague, or leptospirosis, had killed large numbers of Wampanoag and other native Americans along the Eastern coast from 1616 to 1619, following visits by European explorers. The Wampanoag village of Patuxet, located where English colonists in December 1620 would found the city of Plimouth (later Plymouth), had essentially been wiped out by the time the Mayflower arrived. Thus, as writer Glenn Alan Cheney would observe in his book Thanksgiving: “No one owned or claimed or even wanted the land around Plymouth. A miraculous combination of wind, waves, and winter had brought the Pilgrims to one of the few places on the planet that didn’t belong to somebody.”

The truth of this observation depends on the definition of the words “owned,” “claimed,” “wanted” and “belonged,” but the land at Plymouth was indeed unoccupied. And while Cheney’s turn of phrase about the Pilgrims’ arrival in the New World is evocative of Meltzer’s observation about the first Native Americans’ arriving in North America and finding “nobody else was home,” there was a signal difference: The English colonists would be surrounded by people who could teach them how to survive. This proved, in a word that the most religious of the colonists might have used, providential.

An Ill-Fated Beginning

The people who sailed to America in the Mayflower on Sept. 6, 1620, were a somewhat motley crew: some 30 sailors who would transport the colonists to the New World and then return home; 37 “separatists” who had rejected the Church of England and had tired of their de facto exile in the Netherlands, where they had encountered questionable cosmopolitan mores and a labor market that relegated them to menial work; and 64 “strangers” (in the separatists’ eyes), who, like the separatists themselves, were traveling to the New World as part of a commercial venture to create a trading colony that would provide valuable lumber, pelts, salted fish, and other wares for export to England. An unusual combination of religious and profit motives was in play.

The expedition’s ambitious goals were belied by its execution. After two false starts with a leaky companion ship inaptly named Speedwell, the Mayflower finally departed at a time of year when seasonal Atlantic storms were expected. The bad weather struck not long after the ship departed. A particularly harsh storm weakened the ship’s main beam, leaving its mainmast unable to bear sail, and only a jack packed by one of the passengers and jury-rigged to support the beam allowed the ship to sail on. When the Mayflower dropped anchor at the landward tip of Cape Cod, it had arrived well north of its intended destination after a 66-day trip on which it had averaged less than 2 miles per hour.

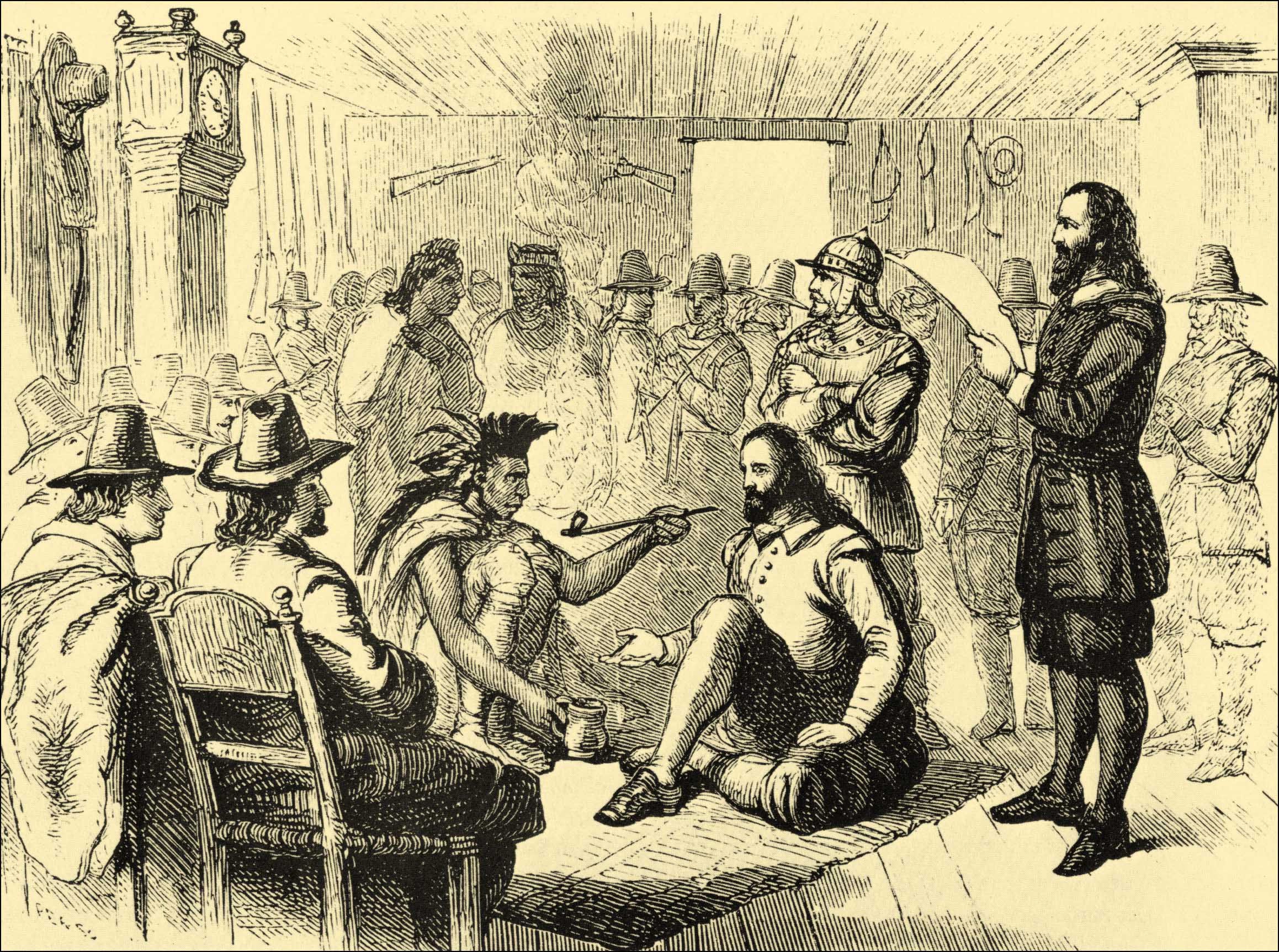

Landfall was followed by a pair of blundering land expeditions on the cape itself. The Mayflower’s shore party clothed themselves in steel vests and helmets and lugged around pikes and halberds ill-suited to the terrain and to any combat they might have had with the Wampanoag, whom they did in fact see and chase a few times. Driven by curiosity and by hopes of finding food, they ultimately excavated a couple of graves and some basketed corn that the Native Americans had stored underground, perhaps planning to pay later, perhaps not. Not surprisingly, men of the Wampanoag’s nearby Nauset tribe eventually fired arrows at the English (to no effect), breaking off the attack when the English replied with a few musket shots. The Englishmen’s subsequent expedition to Plimouth itself convinced the Mayflower’s passengers to settle there.

But they had no shelter ashore, so they slept aboard ship and commuted to land each day to build homes, returning in the evening. The settlers, who were now some 700 miles nearer the equator than they’d been when they left England, hadn’t realized how cold this “New England” would be, hadn’t known they would be unable to plant in November, didn’t realize till later that the seeds they brought wouldn’t grow in American soil. Their stores were low, and the severe wet and cold took the lives of roughly half their number by the time spring arrived.

An Improbable Resolution and Thanksgiving

Against all odds, their luck turned. One day in March, a lone native openly approached the settlers and called out, “Welcome, Englishmen.” His name was Samoset, and he hailed from present-day Maine, where he learned English from the European fishing fleets. He told the settlers they could make peace with the Wampanoag. A week later, he brought his Patuxet friend Tisquantum (later dubbed “Squanto” by the English). Tisquantum spoke even better English, having been to England after fleeing Spain, where he’d been sold after being kidnapped in 1614 by the renegade English captain Thomas Hunt. Tisquantum sailed back to Cape Cod with the English captain Thomas Dermer in 1619 only to arrive in Patuxet and find his tribe had been destroyed by disease.

Tisquantum stayed with the Plimouth settlers in the coming months, showing them how to plant corn and guard it from foraging wolves; how to find nuts, herbs, roots and berries in the forest; and where to fish for eel and smelt. In the meantime, the colonists concluded a peace agreement and military alliance with Ousamequin of the Pokonoket tribe. He was the Wampanoag’s supreme chief, or “Massassoit.” The coming years proved him generous, sensible and shrewd; he had likely engineered the settlers’ casual meetings with Samoset and Tisquantum in the first place.

The truce and alliance proved mutually beneficial and slowly led to a reciprocal respect. In the autumn, about one year after their arrival, the settlers decided to hold a feast in celebration. Perhaps observing the preparations from a distance or hearing the colonists’ gunshots as they hunted for the festival, various Pokonoket and even Ousamequin himself arrived. The people of Plimouth invited them to join the feast, and ultimately some 90 Pokonoket celebrated with the 50 colonists, contributing deer and other food to what became three days of festivities. This was probably not conceived as an annual holiday or a strictly religious gathering, but it was worth remembering. A journey that had started with ill omen some 14 months before in the Old World had concluded with a storybook ending in the New World.

A Less Happy Postlude

It would be hard to describe the 400 years that have followed that early celebration as a happy extension of that opening chapter of emerging harmony. Take the case of the Plimouth Colony alone. Peace prevailed through the lifetime of Ousamequin, known to the English as “Massasoit,” in 1661. But as Cheney describes it, “By the 1650s, Plymouth was expanding into Wampanoag territory. Conflicts over land and straying cattle were resolved in English courts, usually to English advantage.” With Massasoit’s death, things changed:

Massasoit’s son, Metacom, would not show such loyalty [to the English], and he had little reason to do so. The Puritans who moved into the area in the 1630s were less tolerant of the people they were displacing. After a series of deceptive land deals and invasions of Indian fields, Metacom, who came to be known [to the colonists] as King Philip, organized a war against the invaders. It started in 1675. A year later, the settlers, many of whom refused to fight against their Indian neighbors, had lost six hundred people and twelve villages. The English killed three thousand Indians, destroyed innumerable villages and fields, sold captives into slavery, killed Metacom, drew and quartered his body, and displayed his head in a public square in Plymouth for a year.

One didn’t have to endorse Metacom’s sudden and appalling attacks to lament the loss of his tribes’ goodwill. Mercy Otis Warren, the 18th century American intellectual who penned the first history of the American Revolution, was a thorough partisan in the American cause, as well as a Massachusetts woman well aware of the threats that Native American tribes had posed to the American colonies during the War of Independence. Yet reflecting on Metacom and the Native Americans’ response following Massasoit’s passing, she observed that people of every culture were “equally tenacious of their pecuniary acquisitions” and “that the alienation of [the Native Americans’] lands for trivial considerations, the assumed superiority of the Europeans, [the Europeans’] knowledge of arts and war and perhaps their supercilious deportment toward the aborigines might awaken in them just fears of extermination.”

Indeed, writing after the Revolution, at the dawn of the 19th century, Warren reminded her readers, “The unhappy race of [Native American] men hutted throughout the vast wilderness of America were the original proprietors of the soil.” She worried, “However the generous or humane mind may revolt at the idea, there appears a probability that they will be hunted from the vast American continent, if not from off the face of the globe by Europeans of various descriptions, aided by the interested Americans.”

Aiming for Better

We may not have quite achieved that dystopia, but official efforts to protect the rights of the Native Americans West of the Appalachians first by the British crown in 1763 and then by the United States’ fledgling liberal democracy in The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 did not end nobly, negated by constant encroachment of new settlers and by reciprocal acts of barbarity and retribution. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, ostensibly meant to allow the U.S. government to peacefully entice the Eastern tribes to give up their current homes in the East in return for a supposedly perpetual right to land west of the Mississippi River, was ultimately realized by coercion, with some 100,000 Native Americans placed on a forced march to the West—one in which an estimated 15,000 died. The California Gold Rush of 1849 ensured more Americans settlers would travel west of the Mississippi River, leading to new encroachments on Native American lands and new conflicts that culminated in the brutal Plains Wars of the latter 19th century.

The rights of Native Americans also lagged behind the liberal theories of American democracy. The Fourteenth Amendment, passed in 1868, guaranteed “all persons born or naturalized in the United States” the “privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States”—a seemingly broad statement of human rights—but as late as 1879, the Ponca Chief Standing Bear had to fight in a U.S. court for the right to be recognized by U.S. law as “a person” and enjoy free movement outside an Indian reservation. The ruling in his favor, rendered by federal judge Elmer Dundy, is a searing yet methodical statement, both inspiringly and tragically American. The Fifteenth Amendment, passed in 1870, guaranteed citizens of the United States the right to vote regardless of “race, color or previous condition of servitude,” but the enfranchisement of Native Americans, complicated by murky legal relationships between federal, state and Native American jurisdictions, was effectively delayed until the Snyder Act of 1924 granted Native Americans full U.S. citizenship and the 1965 Voting Rights Act ended their de facto exclusion by many states at the polling booth.

For all this, Native Americans have the highest poverty rate and the lowest mean and median incomes of any U.S. racial group. Land reserved for Native Americans has long been subject to dispute and contentious litigation. The growing caseload of unsolved disappearances and killings of Native American women is now a national concern.

It is a hard truth, but a truth nonetheless, that the classical liberal ideals and individual rights on which the United States was founded were born in a time of slavery and imperialism throughout a largely illiberal world. Liberal ideals have slowly—very slowly—purified that mixed inheritance, and for that, and for a country legally dedicated to liberal ideals and freedoms, we can be thankful.

But this gratitude, and our ideals, should also be expressed by a consciousness of the incompleteness of our liberal striving, a frank acknowledgment of times when the American polity has failed to live up to its ideals, and a greater public attention to the pressing concerns of people whose ancestors “were the original proprietors of the soil,” and who lent a hand, many times at cost, to those colonists and citizens who founded and formed the country we now call home.

Thomas Shull is editor-at-large of The UnPopulist.

I have heard it mentioned, but more so in the past than I have recently. There's no denying there was some highly illiberal and inhumane behavior by various Native American tribes. You raise a fair point. I debated discussing some of this and decided against it given the length of the piece already; I figured Metacom's attack would have to stand in for it.

Native Americans also played a significant role in the American Revolution - it's a messy, complicated history. There was one story I read about the chief of the Wappinger Nation, who sided with the American rebels, and died fighting the English in a band of his tribesmen and New York militiamen, and I'm sure that wasn't the only time that happened. So much to be grateful for in American history, along with so many errors to learn from.