All Sides Are Violating International Law in the Escalating Middle East Conflict

If Israel, its neighbors, and the Palestinians played by the rules of war they could forge a path to peace

Thousands of pagers and walkie-talkies exploded in Lebanon over multiple days, in an unprecedented operation, presumably by Israel, targeting the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah. At least 37 people are dead, and thousands more are injured. Nothing like this has happened before, and the global implications will have a long tail.

Critics of Israel such as Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez objected. Citing the U.S. Defense Department on the laws of war that forbid booby-trapping “apparently harmless portable objects” with explosives, the New York congresswoman denounced the attack as illegal.

On the legal question, Israel would have a case. The passage Ocasio-Cortez cited specifies that international law prohibits “the production of large quantities of dangerous objects that can be scattered around and are likely to be attractive to civilians, especially children.” For example, it’s illegal to put explosives on toys, or cell phones that anyone could buy in a store. By contrast, the devices Israel tampered with were purchased by and transferred to Hezbollah, not scattered around, and their intended uses included military coordination.

When we move past legal questions, it gets more complicated. The attacks knocked out a lot of Hezbollah communications—not just by destroying the devices, but also by making Hezbollah fear that anything they have could be compromised—which will hinder the group’s activities, at least for a time. The dead and injured are primarily Hezbollah operatives, resulting in a military-civilian casualty ratio that looks good compared to wars in general, and a lot better than Israel’s operations in Gaza, which have killed tens of thousands of civilians, many of them children.

But that doesn’t mean it was precise. In a military context, “precision” typically refers to directly hitting a known target, such as a U.S. drone strike killing al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in 2022. There’s no way Israel knew exactly where thousands of pagers and walkie-talkies were when they triggered the explosives, nor who was in proximity to them, except that many were likely carried by Hezbollah members or associates. Some went off in groceries. The attack killed and maimed innocents, including kids and civilian health workers, in addition to numerous militants.

A lot depends on what happens next. If it sets off an escalatory spiral that leads to full-scale war in Lebanon—or worse, regional war with Iran—that’s bad. If it weakens Hezbollah to the point that they cut a deal and move back from the Israel-Lebanon border, with both sides curbing aerial attacks and allowing thousands of displaced people on either side to return home, that would be good. And there are many possibilities in between.

For now, Hezbollah says it will keep firing until the Gaza war ends, and recently shot missiles deeper into Israel than before. Israel refuses to end the Gaza war in a way that lets Hamas reconstitute control of the territory and rearm, and has escalated airstrikes in Lebanon.

No matter how courts would adjudicate the legal technicalities, it’s not something international law can manage.

Every State Has Violated International Rules and Standards

International law isn’t the same as morality. War is inherently awful, and the laws of war allow a lot of terrible things, including a degree of civilian casualties. There are some straightforward cases of illegal aggression—for example, Russia invading Ukraine in pursuit of conquest—but it’s rare, and often breaks down when getting into details.

With the current conflicts in Gaza and across the Israel-Lebanon border, everyone is violating international law in multiple ways. And anyone who wants to claim they’re merely retaliating to their enemies’ attacks can roll back the clock and find something.

Israel’s initial response to Hamas’s Oct. 7, 2023 attack—which killed over 1,100, mostly civilians, and took 251 hostage—included cutting off Gaza’s water supply. That’s collective punishment, a violation of international law. Facing widespread condemnation and pressure from the United States, Israel dialed back after a few days.

Then Israel launched a full-scale invasion of Gaza. Going to war against Hamas was legal, as a self-defense response to Oct. 7. But Israel’s actions have violated international law in multiple ways, including disproportionate use of force, killing aid workers and journalists, and failing to sufficiently avoid harm to civilians.

Hamas using force against Israel is arguably legal, because Israel has imposed a blockade on Gaza for years, which is an act of war. But Hamas’s actions violated international law in multiple ways, deliberately targeting, killing, and kidnapping civilians. (That contrasts with Hamas’s 2006 kidnapping of Gilad Shalit, who was an Israeli soldier manning an IDF post, and therefore a military target.) The Oct. 7 hostages have been subjected to conditions that violate international laws regarding treatment of prisoners of war.

Under the Geneva Conventions, civilian hospitals are off limits. Armed forces operating out of a hospital is a war crime, effectively making the medical staff and patients into human shields. By using Gaza hospitals for military purposes, Hamas turned them into legal military targets.

But international law also requires advance warnings, efforts to evacuate hospital personnel before attacking, “all feasible precautions” to avoid harm to medical staff, patients, and other civilians, and strict proportionality in the use of force. That means some of Israel’s attacks on hospitals constitute war crimes, even if Hamas fighters, hostage-takers, or commanders were operating there.

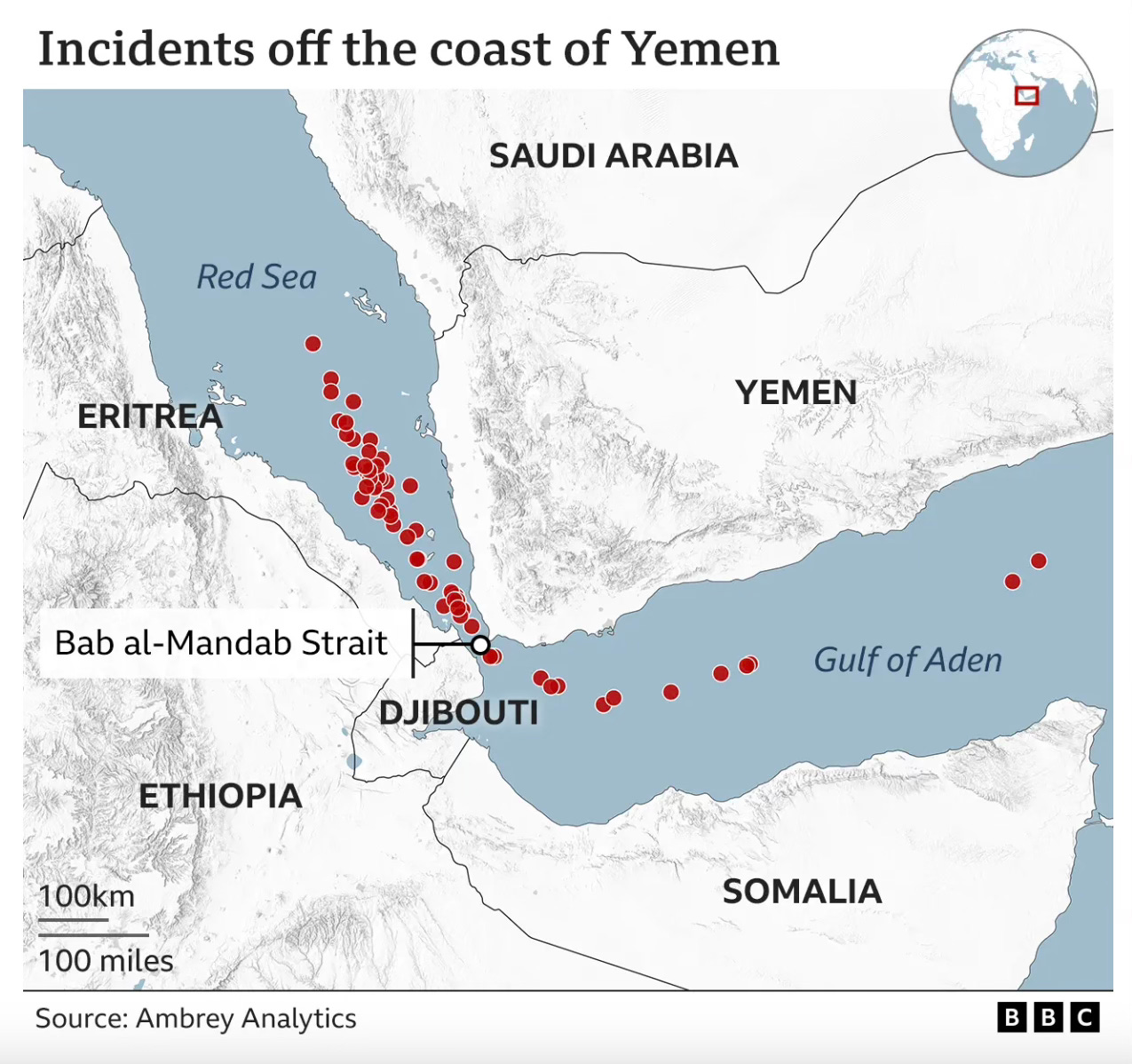

Hamas and Israel aren’t the only ones violating international law. The Houthis, an Iran-backed group that has been fighting in Yemen for years and controls much of the country’s west, has been firing into international shipping lanes in the Red Sea. They claim it’s in support of Gaza, while many analysts think it’s really about the Houthis’s power in Yemen and the region. Legally, it doesn’t matter.

Attacking commercial ships is illegal, including when you say you did it in solidarity with a righteous cause. And it’s worth noting that none of the ships the Houthis have attacked are Israeli or involved in the Gaza war. Hit vessels include ones flying the flags of Belize, Liberia, and Greece.

Seeing these attacks, some pro-Palestine voices in the United States cheered the Houthis. Besides violating international law by firing at commercial ships, the Houthis have been under U.N.-authorized sanctions for numerous illegal actions, including restricting water to a city of more than 500,000 people. Unlike Israel, they have not resumed the flow in response to outside demands.

Hezbollah, Israel, and the Limits of International Law

Hezbollah also claims its attacks are in solidarity with the Palestinians, and is also violating international law in the process. Much of their rockets are inaccurate, indiscriminately fired at populated areas, and have killed civilians, including children (though fewer civilians than Israel has killed in Lebanon, in part due to Israeli air defenses). Sustained rocket, missile, and drone launches over the last year have depopulated Israel’s north.

Hezbollah’s ability to do that constitutes a broader violation of international law. The group’s presence in southern Lebanon violates a binding 2006 U.N. Security Council Resolution (1701), which mandates no armed forces south of the Litani River—which is about 18 miles north of the Israel-Lebanon border—except for Lebanese government and U.N. peacekeepers.

According to Hezbollah, its presence there is justified by a small part of the Golan Heights called Shebaa Farms, which is claimed by Lebanon. Israel annexed the Golan Heights in 1981, but under international law it is occupied Syrian territory, captured in the 1967 and 1973 Arab-Israeli wars.

More broadly, Hezbollah considers itself a leader of armed resistance against Israel, justified by the occupation of Palestinian territory. The apartheid-like structure of the West Bank—with Israeli settlements, exclusive roads, and checkpoints for Palestinians—defies multiple U.N. Security Council resolutions. East Jerusalem, which Israel captured and annexed in 1967, is considered disputed territory under international law. But Hezbollah doesn’t advocate a two-state solution, or a single state with equal rights—the group seeks Israel’s destruction.

This is when Israel’s supporters usually say “Israel has the right to exist” and “Israel has the right to defend itself”—which it does under international law, as a recognized sovereign U.N. member state. The law allows considerable use of force, including attacks on military targets that result in “collateral damage” to civilians, which the pager and walkie-talkie explosions arguably fit under.

But the right of self-defense doesn’t mean the right to do anything in response to an attack. Nor is there any law that says that until Israel-Palestine is solved, anti-Israel groups can attack however they want.

This situation is beyond the limits of international law. Every combatant involved has violated it many times, to varying degrees. Their military capabilities, and their position in the broader Middle East power competition between coalitions led by the United States (Israel, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates) and Iran (Hezbollah, Hamas, Syria, Houthis, Iraq and Syria-based Shia militias) mean the law won’t be enforced against them. The failure of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon after the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war, and the ongoing failure to broker an end to the Gaza war, are among the biggest examples.

Aspects of international law remain something to aspire to, but this situation is being governed by power.

It’s easy to envision an end state for Israel, Gaza, the West Bank, and Lebanon that sounds fair to outsiders. But local participants have the ability to forcefully prevent movement towards one they don’t like. The hard part, the thing no one has been able to figure out, is not imagining peace—it’s getting there.

A previous version of this essay first appeared in Arc Digital. It is reprinted here with permission.

Unfortunately, an instance of ahistorical analysis. Mr. Grossman's analysis starts at Oct. 7, and then proceeds to tally up which side did which action in violation of international law. This ignores the ongoing position of many of the states around Israel that they want to kill and get rid of all Jews from the Middle East. To write this standard analysis of supposed moral equivalence ignores the blatant fact that Israel wants to live in peace with all around, and cannot do so because of murderous people in many directions.

Your position claiming that Israel violated human rights laws or principles with the pager attack is illogical, incorrect, and extremely offensive.

I don’t care about your objectives or intentions. You are only providing cover for terrorists with this claim.

Absent a retraction I have no expectation will be forthcoming, I will make a point to never read anything you write again.

You are surely NOT defending liberal democracy with this claim.